Two years ago, while I was still studying war and conflict, I presented a paper on the need to consider social media in our understanding of political violence, propaganda, and war narratives. The focus was on Ukraine’s Azov battalion– an independent, right-wing, armed militia that later got fully integrated into the Ukrainian army – and their sudden surge of popularity among Ukrainian civilians. The point was that images travel much more quickly than before, because of social media but also due to communication apps such as WhatsApp, Telegram, Signal, and so on. At that time, I would get live updates on Russian prisoners captured and people injured on the ground from a Telegram channel managed by the battalion itself. Grassroots journalism also became this endless source of information through Instagram and Reddit, where again I could get live updates on conflicts with images before mainstream media would pick up on them.

One of the main concerns raised at that time was about the authenticity of the image and the need for media literacy regarding this kind of news and media consumption. This is still very relevant.

I recently had to give a presentation on my current research, and I bluntly claimed that social media is photography, which started a heated debate – a debate I never thought would take place. I was explaining to my friend P, during one of our biweekly coffee meetings, that I got hit back with a familiar response: ‘It’s from your generation; it’s not innate to everyone.’

The generational argument has always annoyed me, because it’s dismissive to divide our understanding of technology according to the age of the population. My mom is on TikTok and my dad is on Instagram, and even if we have different types of engagement or levels of facility with the apps, they still can recognise the importance of such platforms in today’s world. The debate went on about how the history of photography proves me wrong; I still don’t know what that means, or even what it refers to, because the history of photography is very much intertwined with the development of new technology and media.

Back to our coffee. Even P struggled to understand why the statement ‘social media is photography’ provoked such intense debate amongst photographers, noting that if someone wants to look at and understand our society today, it’s imperative and even obvious to include social media and technology in the reflection. We went back to her place because she had to pack to go to Ukraine: it’s a difficult task to pick outfits to go to a war zone, and she needed help from her trusted friend – me.P is not part of any military organisation.

‘I’ve seen all these TikToks of Ukrainian young adults showing what life under war conditions is, and I thought maybe I should make a TikTok – “pack with me to go to a war zone” – but I think it would be offensive.’

I thought it would actually be really funny and a good comment on the situation, it is a new reality for many of us: social media is an integral part of our daily lives, and especially for women.

You’re probably wondering why women on social media, beauty standards, and war coverage are being grouped together here. Well, first, because I’m a young woman using social media; second, because two of my favourite topics are girls on the internet and conflict documented by grassroots journalists; and third, because both exist thanks to networked platforms. I like to look at photography as this ever-morphing medium that can be unframed and can challenge itself and its own boundaries. So what if social media allowed photography to go in a new dimension – one that’s democratised and accessible and allows for an undefined approach? In this way, problems of authenticity and objectivity could be tossed away, because it's tempting to believe social media can be objective, but at least it’s honest in its deceptive nature. In this piece, I’ll focus on war photography, women, and social media, and how these three elements have radically evolved and changed our perceptions and understanding of conflicts. The power of images, of a photograph, has never been contested – it has been questioned, for sure, and debated too, but it holds power. This power takes many shapes, and maybe in 2024, a cute soldier making a TikTok in their uniform is the new way of understanding (war) photography and propaganda.

The soldiers of TikTok are, to me, what Afghan women were to the US during the invasion of Afghanistan and the Middle East. A decoy. Women and war have always been a great topic, skipping the conversation on the common essentialisation of women as peacemakers; the identity of women, their bodies and their clothing have always been a weapon to support war. And visually, one that convinced.

In 2001, Congresswoman Carolyn B. Maloney wore a burqa during an assembly at the US House of Representatives to plead for the rights of Afghan women and press the need to save them from the Taliban; hence invasion was justified and more money was needed. This image (see Twitter post) deeply shocked America, not just because it was the first time a burqa had entered the sacred House of Representatives how representative of a supposed lack of freedom. As Wendy Kozol wrote, there is a need ‘to recognize visual witnessing as enmeshed in the historical problematics of neocolonial spectacles of power and dominance.’Wendy Kozol, ‘Visual Witnessing and Women’s Human Rights’, Peace Review 20, no. 1 (2008): 68.

In a memo leaked by Edward Snowden in 2010, we find a CIA intel document titled ‘CIA Red Cell Special Memorandum; Afghanistan: Sustaining West European Support for the NATO-led Mission’ written in March 2010.This report can be read on wikileaks: https://file.wikileaks.org/file/cia-afghanistan.pdf The memorandum is subtitled ‘Why Counting on Apathy Might Not Be Enough’, and it explained how support for interventions led by NATO and ISAF was slowly decreasing in Europe. The report presents an overview of what could work and what might not in terms of communication to raise support for military intervention in Afghanistan.

The document highlights the fact that European women (especially French and German women) are less and less supportive of such intervention. According to the CIA’s statistics, in 2009, French women were 8% less likely to support intervention than men; in the case of German women, the number went up to 22%. The report presents a simple solution: ‘Afghan women could serve as ideal messengers in humanizing the ISAF role in combating the Taliban because of women’s ability to speak personally and credibly about their experiences under the Taliban, their aspirations for the future, and their fears of a Taliban victory.’

The publication of this memorandum followed Dutch troops’ withdrawal from Afghanistan due to a lack of public support from Dutch citizens. The CIA feared the same thing would happen with Germany and France. The media campaign recommended by the CIA was to show and publish the testimony and stories of Afghan women to influence and specifically target women’s public support. By doing so, the CIA hoped European women would try to relate, calling on the principle of ‘sisterhood’ to ‘overcome pervasive skepticism among women in Western Europe toward the ISAF mission.’

OK, so far, I have yet to demonstrate how social media has bent the rules of political communication. Victimhood has limits; apathy not so much. The narrative around Afghan women as victims was met by a lot of resistance – by Afghan women first and foremost, but also by a feminist reading and refusal to allow not just the instrumentalisation of a struggle but also its weaponisation. On the other hand, the story met an end quite quickly – or after 20 years. When a war lasts so long, it’s difficult to justify it by showing how it deteriorated the living conditions of the population it purported to be ‘saving’. Does this mean that, as a society, we don’t find the aspirations of women interesting enough?

Now, here comes TikTok, a platform ruled by the tyranny of the patriarchy promoting hegemonic beauty standards like death sentences. The ‘victim’ side of the war does not work anymore: young people are apathetic in the face of images of destruction and don’t care about blood. Read this as an intelligence agent, at least 50 years old, for any military office you can think of. What’s trending nowadays, what influences opinions, and where do these youngsters get information and education? Once you understand the logic of social media, it’s easy to insert war propaganda in there.

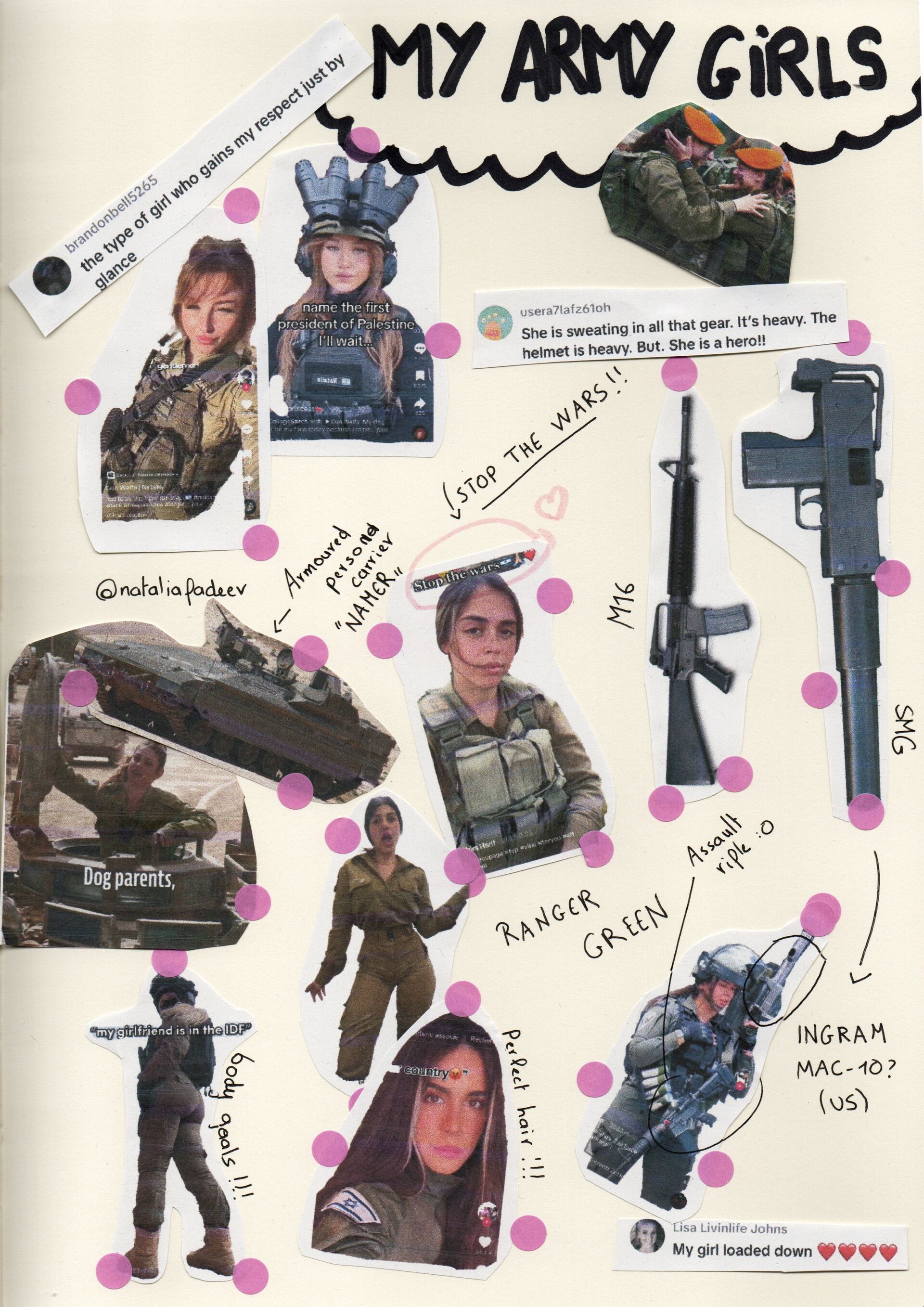

The formula is simple:

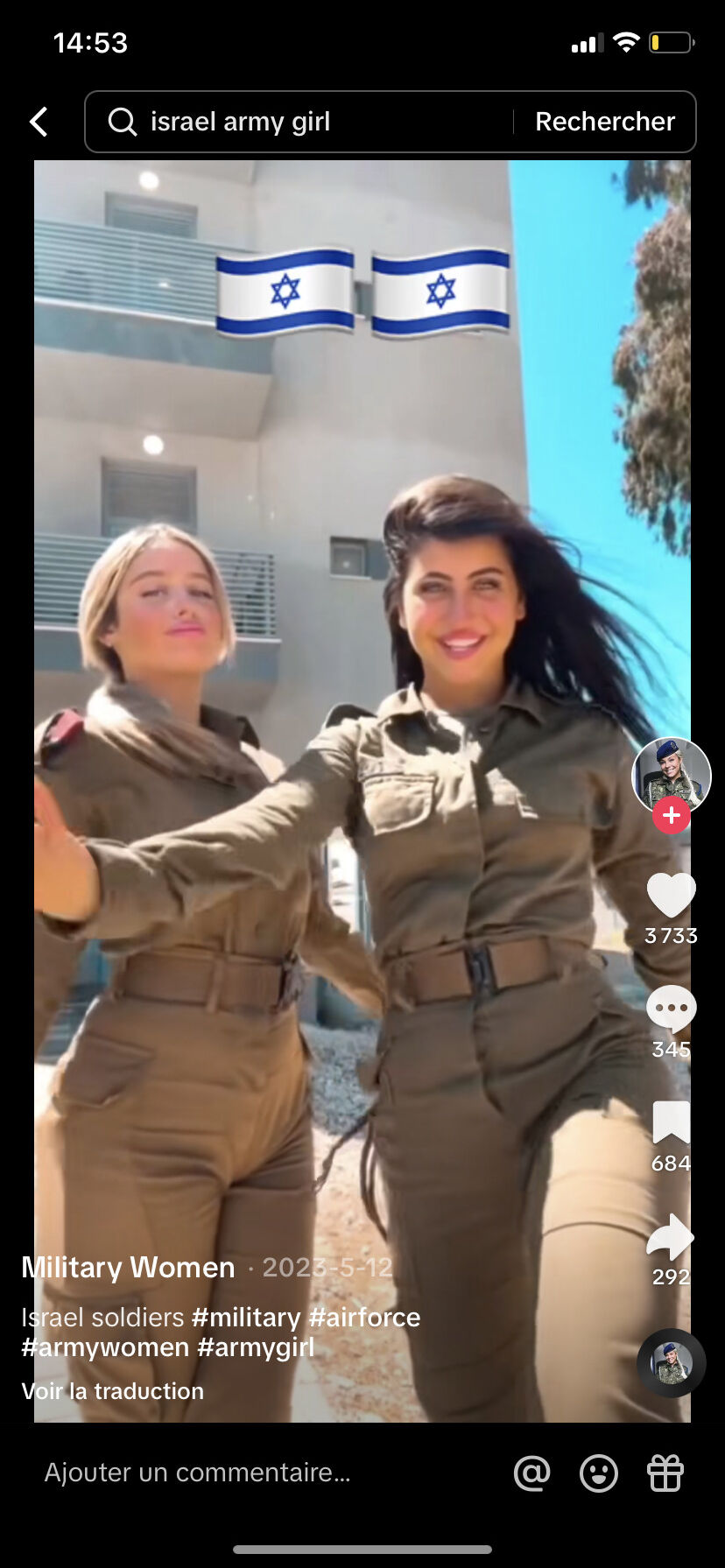

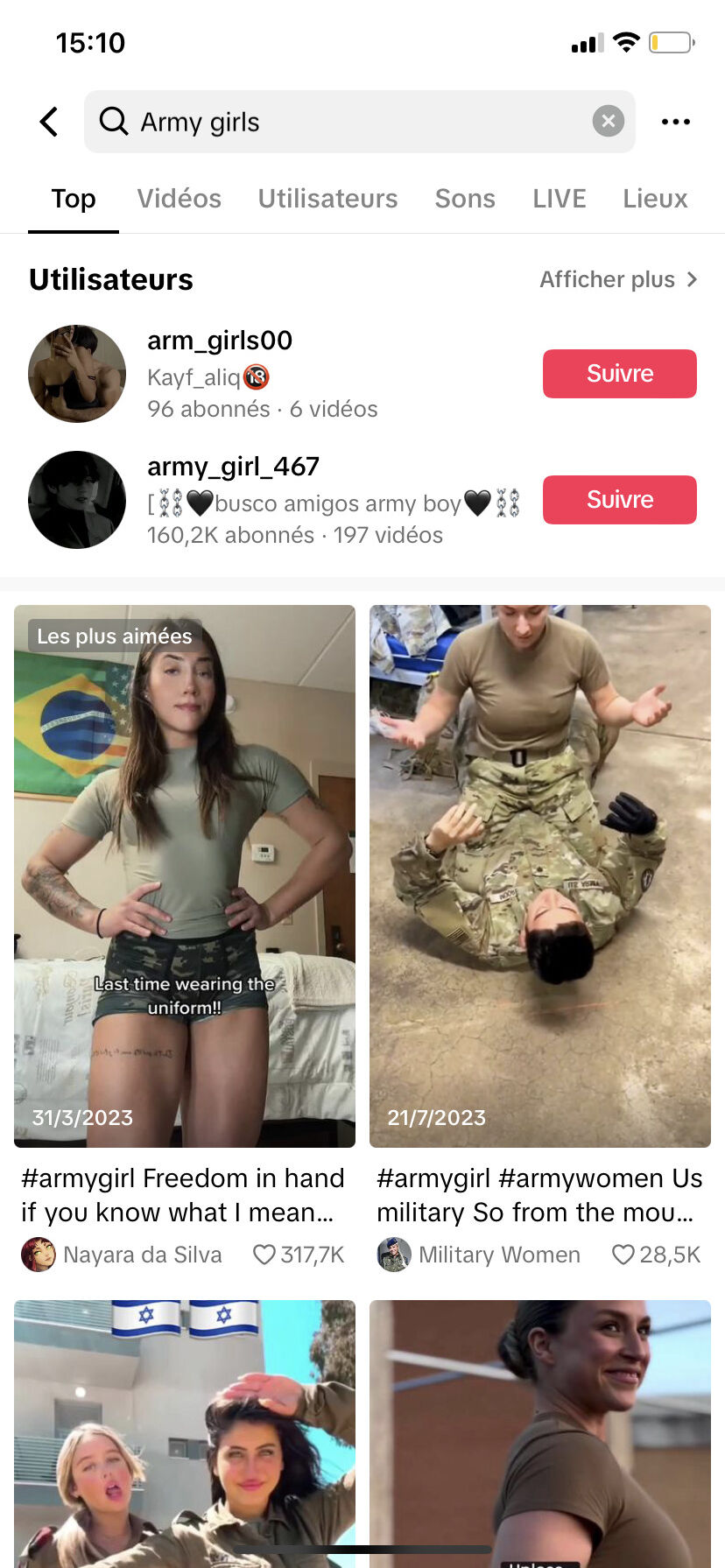

cute girl + sexy uniform + trendy music /sound + dance = yay! war!

extras: big guns*My friend L kindly added that big guns = big dicks.

This time, we’re not looking at the people we invade but rather at the invader. Soldiers from the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) are among of the most prolific ‘Yay! War!’ content producers on TikTok. This is where my conversation with my friend P got all its substance. Even if her outfits weren’t military uniforms, it would still have been more engaging to watch her getting dressed to go to a war zone than to see the actual war zone, as it’s more interesting for a lambda user of TikTok to see a sexy soldier of the IDF than Palestine under siege.

The military is an inherently sexist environment, and as very well synthetised by Aili Mari Tripp, ‘human agency is not of or for women, but directed to what the military can get women to do to meet their objectives of pacifying a population. Giving a human face to the military is not what human security is about.’ In this case, we’re looking at diversion – to speak in military terms. When searching for ‘girl soldier’ or ‘army girls’ in TikTok’s search bar, a profuse amount of videos are presented to me. Sex sells; pretty girls too. The exploitation of women didn’t stop with the withdrawal of American troops from Afghanistan; it just became more basic, closer. Why show misery and destruction when you can promote your politics through beautiful ladies? In an article titled ‘How E-Girl Influencers Are Trying to Get Gen Z into the Military’, Günseli Yalcinkaya writes that ‘we’ve entered an era of military-funded E-girl warfare. In what would’ve felt unimaginable only a few years back, influencers are the hottest new weapon in the government’s arsenal.’Günseli Yalcinkaya, ‘How E-Girl Influencers Are Trying to Get Gen Z into the Military’, Dazed, 10 January 2023, https://www.dazeddigital.com/life-culture/article/57878/1/the-era-of-military-funded-e-girl-warfare-army-influencers-tiktok.

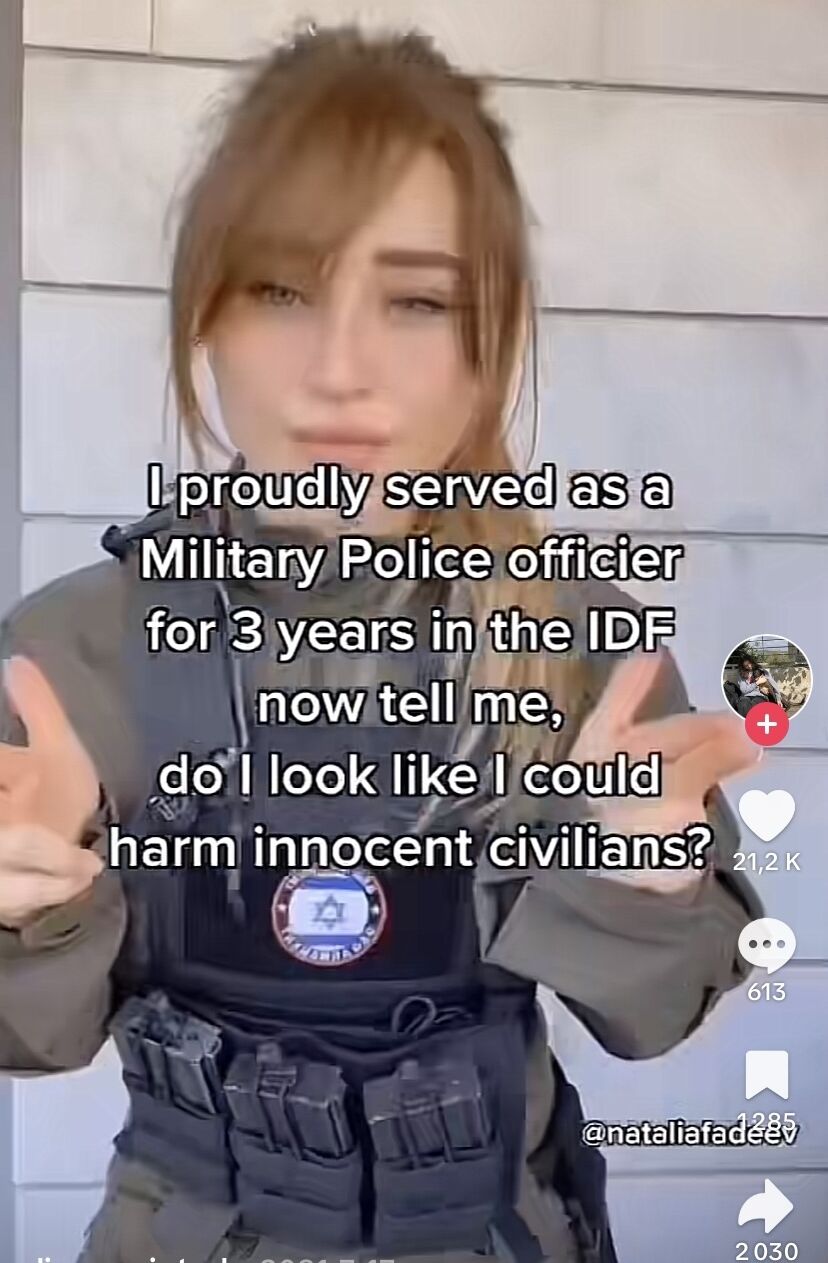

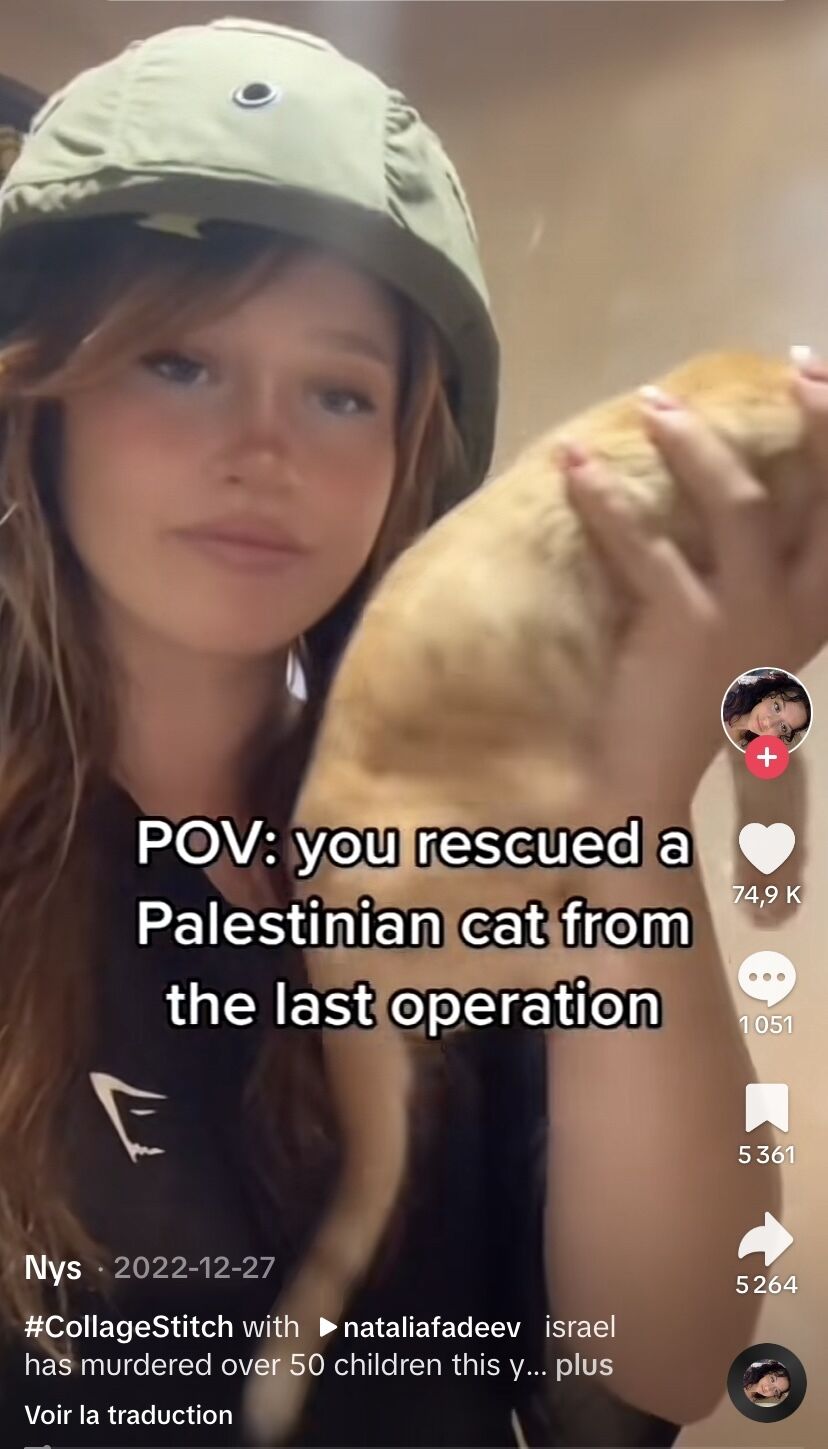

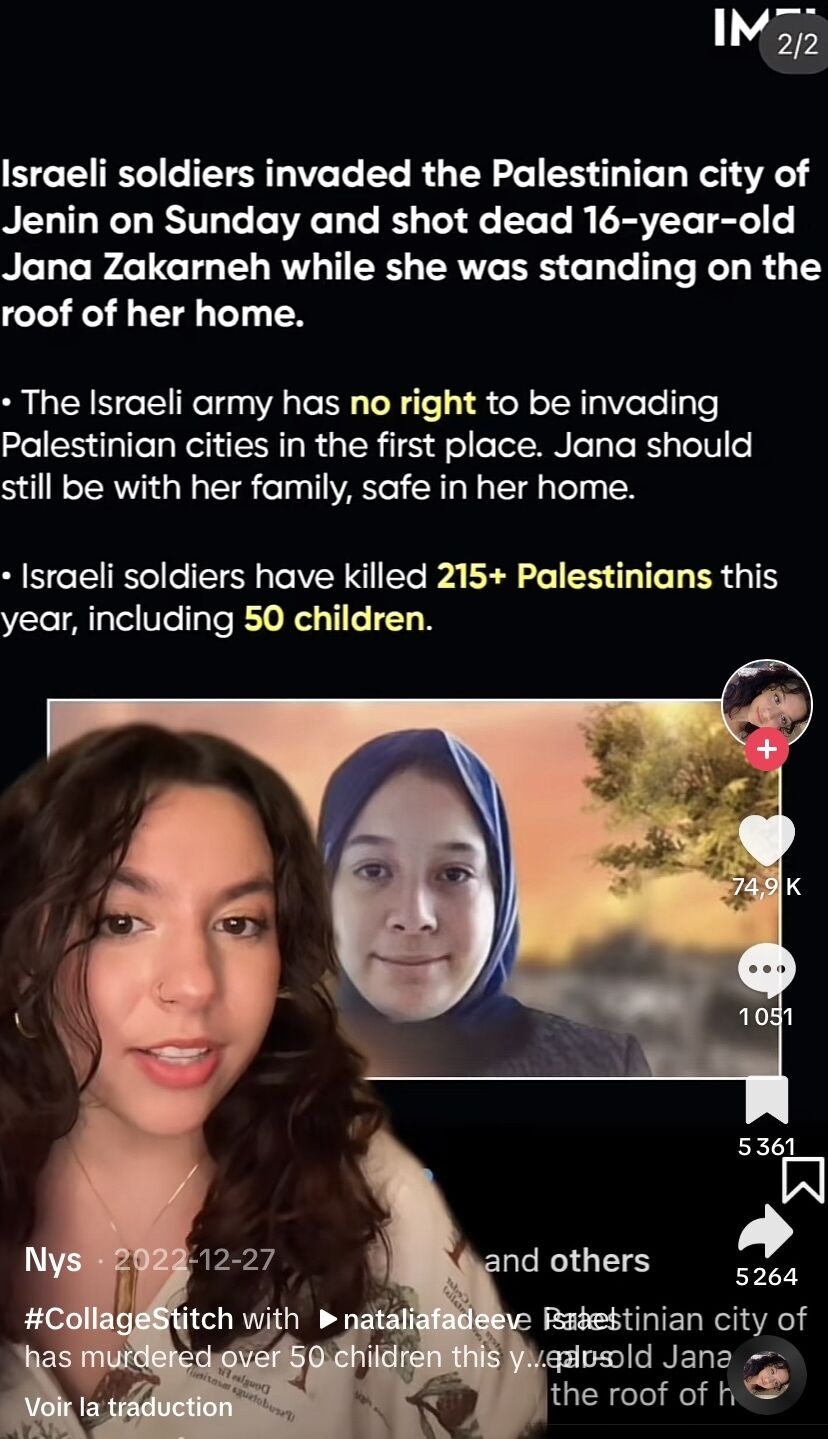

This constitutes a mere rebranding of war imagery, shifting away from explicit depictions to subtler visual cues associated with conflict: uniforms, weaponry, and military settings. The portrayal of women has evolved; they’re no longer presented solely as victims but are now intertwined with a dubious allure, perpetuating the fantasy of the ‘sexy soldier’. Under the guise of empowerment and a distorted form of feminist ideology, these ‘army girls’ symbolise political ideals while masking the grim realities of warfare. Because, as @nataliafadeev puts it, ‘could a girl looking like this really harm civilians?’

By perpetuating Western beauty standards – white, patriotic, and conforming to hegemonic ideals –these depictions obscure the brutality of war behind a facade of beauty. Given the inherently gendered structure of the military, women are invariably objectified through the lens of the male gaze, their representation tailored to fulfil male fantasies.

As a young woman, I find it difficult to witness. The ‘army girls’, instrumentalised within a deeply patriarchal institution, inadvertently perpetuate harmful ideologies in the service of war efforts, working in the service of the oppression without considering their own oppression. Within a predominantly masculinist institution, the pressure to prove worthiness and utility drives women to more radical extremes than their male counterparts. This exploitation is facilitated by a neoliberal feminism that reduces women to expendable market entities within post-Keynesian economic paradigms, as criticised by feminists like Hester Eisenstein.Hester Eisenstein, Feminism Seduced: How Global Elites Use Women’s Labor and Ideas to Exploit the World (Paradigm Publishers, 2009).

The new reality of war photography unfolds at the intersection of propaganda, the male gaze, revenues, and engagement on social media. These videos are products, and they’re pushed by the platforms because they generate views and interactions, which means revenue. If you’re good enough at producing content that will generate money and interaction on a platform, that content will be promoted, and your political beliefs with it. This is a game in which the far right and conservative political groups are excelling. It doesn’t need to be spectacular or exclusive anymore, but just accessible – I would dare to say even basic.

Engaging with geopolitics becomes easy: a flag, a khaki outfit, and a big ass distract from the real problems. On TikTok, we don’t talk about Palestine but about how hot Israeli soldiers are. As @cobus commented, ‘You looking very beautiful in uniform’; and @user4792323020836 demonstrated that beauty transcends borders: ‘Beautiful girls 🇧🇷🇧🇷🇧🇷🇧🇷🇧🇷🇧🇷🙏🏻’. In a world where information travels at two-thirds of the speed of light and violent images are overly accessible, war propaganda has found a safe and disengaged public through the sexualisation of women.

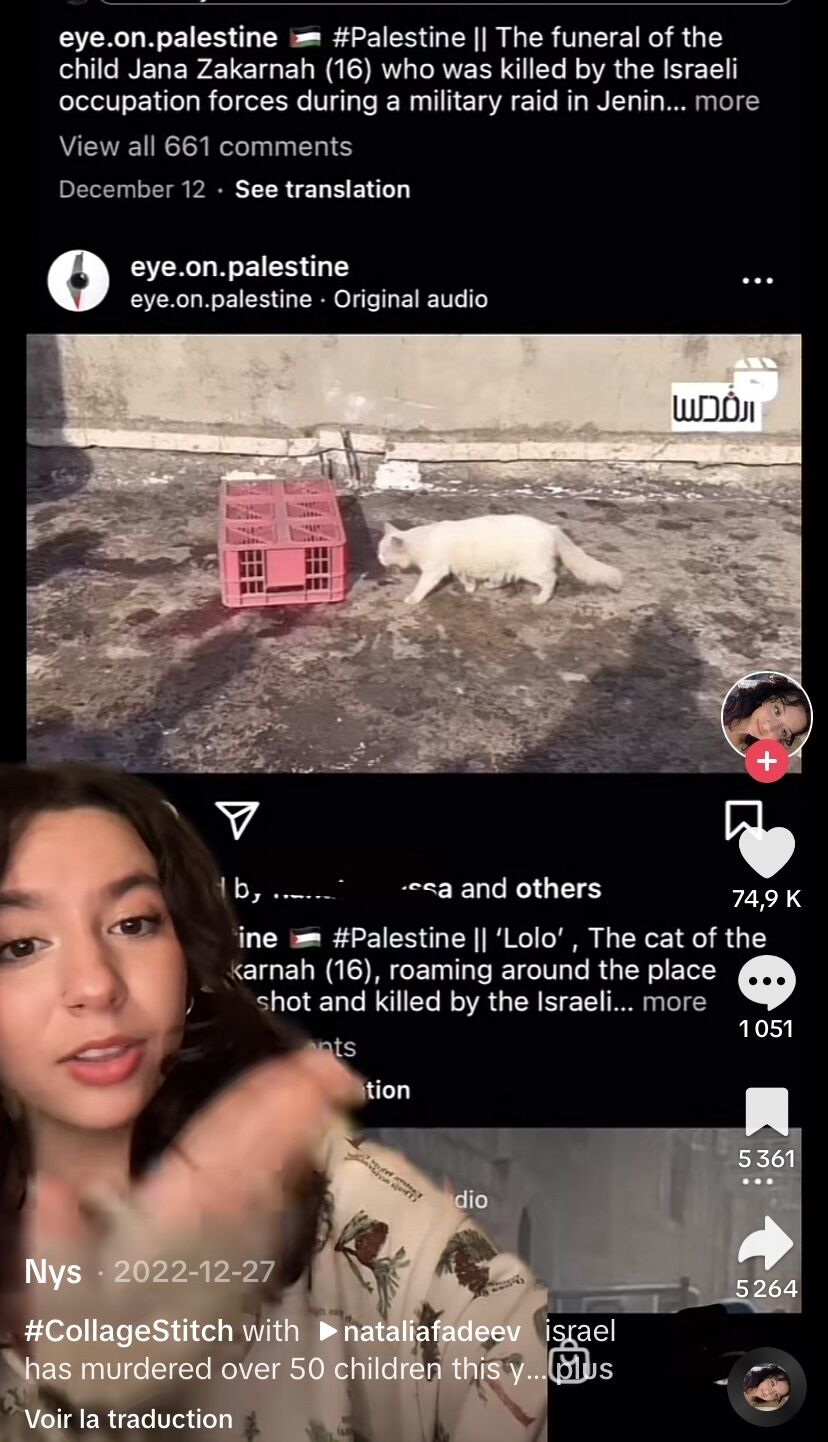

If this is a deeply problematic use of women’s bodies and identities – as hypersexual beings who love war, so you should too – let’s not let it make us totally hopeless yet. The amazing thing about social media is that because of its networked nature, there’s never only one truth. I, an active user of TikTok, unironically engaging with the platform, for example, have encountered these TikToks, but never alone. Because TikTok allows users to ‘stitch’From TikTok’s website: ‘Stitch is a creation tool that allows you to combine another video on TikTok with one you're creating. If you allow another person to Stitch with your video, they can use a part of your video as a part of their own video.’ See HYPERLINK 'https://support.tiktok.com/en/...') videos of other users, I always encountered these thirst trapsSee the definition from the Cambridge Dictionary: ‘a statement by or photograph of someone on social media that is intended to attract attention or make people who see it sexually interested in them’ (HYPERLINK 'https://dictionary.cambridge.o...'). stitched with a critique. If Natalia is afraid we might think she harms civilians, @disappointed is not afraid of pointing out how ridiculous this video is: ‘Are pretty white women the new guardian of national virtue?’

This circles back to my first argument: it’s sometimes dangerous to disregard and be dismissive of another generation’s understanding of social media, because counting on the hormones of teenagers or the lust of adults to divert attention from actual conflicts also reaches it limit. And women are usually the first ones to be rubbed off the wrong way by these strategies, recognising how once again their bodies and looks are used against them but also against others. Natalia’s original account doesn’t exist anymore – what I can find now on TikTok about her are mostly stitches explaining the situation and the context of what is happening in Palestine and critiquing this kind of problematic instrumentalisation.

These stitches are essential to understanding why social media can expand photography’s problem of objectivity and authenticity. Media literacy is not a given, even less so on platforms such as TikTok, where the overflow of information drowns you in a turmoil of mixed content and sound and images and texts and people and comments and #hashtags. Context is not a given; especially with images, and especially in the digital age, war photography always has to be taken with a pinch of salt, and it needs context. Most people have also lost trust in war photography; as a war photographer Don McCullin noted in an interview for the Guardian in 2015, ‘Digital images can’t be trusted’ – they have been ‘hijacked’.Mark Brown, ‘Digital Images Can’t Be Trusted, Says War Photographer Don McCullin’, The Guardian, 27 November 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/nov/27/don-mccullin-war-photographer-digital-images.

McCullin does use digital cameras – ‘because of the pressure, people want things “now”’ – but said he was happier with film, recalling one of his best experiences this year, standing on Hadrian’s Wall in a blizzard: ‘If I’d have used a digital camera I would have made that look attractive, but I wanted you to get the feeling that it was cold and lonely.’Ibid.

What social media, and in this case TikTok, gives back to photographs and images is the possibility of context. Though I could argue that McCullin is as much aestheticising conflicts as those he criticises, this is not my point here. The point is that the medium doesn’t matter as much as the context anymore, and where a picture on a wall with a text presents one reality, social media gives you plenty of alternatives. Objectivity was never achievable, authenticity arguably so. TikTok does not pretend to present reality – it’s presumed that these images and videos have been filtered and curated for a specific audience and to allow others to reappropriate it and recontextualise it. As much as this can be a good thing, it can also be disastrous, and it’s becoming urgent to educate audiences on how to interact with online content.

I believe in photography as a versatile medium that is not stuck in one category, that is fluid and moving with times and users. Images can be feminist and intersectional and fight against oppression while producing it. This ambivalence and paradoxical nature of images is what makes them great educational tools. The nature of photography in general is changing because of the platforms it exists on. I refuse to support the argument that women are victims of social media without understanding the possibilities these platforms also offer to women to free themselves, or at least to reclaim them. If you want to be critical and push it to the other extent, if you’re a product and there’s a dedicated space for you on a platform like TikTok, you can subvert it. It’s obviously difficult for me to understand why women would want to join an institution that’s designed against them, but this is not the debate I’m engaged in here. We need to understand the oppression and the context of these women to understand why they would willingly perform for an audience in the service of destruction. Social media are one representation of a social reality, and because I believe intersectionality is key to understanding the intertwining of struggles, it’s important to understand that the oppression and weaponisation of women through images are as much a product of patriarchal hegemony as war is.

It is then fundamental to give space to social media platforms within photography and visual culture in order to understand our own relationship to the world. I chose the example of war because of its dramatic and impressive nature, but this conclusion can be extended to so many more topics.