What happens when images meet text? An old and obvious question hardly anybody poses, unless they’re an academic. Or an editor like me, trying to work out what a photography magazine like Trigger can be about and what it should do.

Enter Image Text Music. This tiny, handy book has been on my desk for a while. It totally met my expectations of a slow-burning summer read. Taylor – a co-director of the Image Text Ithaca MFA program – wrote such a stimulating meditation on the field of ‘image-texts’, revolving around the conviction that ‘writing always makes images’ and ‘images are always textual’. Nothing less than the entente between photography and writing is in the learning mix here.

Taylor is clear on the kind of intimacy that interests her: ‘Not just texts and images, but an image of their thinking, of their dialectic, their multiple unions, their desires and ours, their conjugal music, their interminable penetration of each other and of us.’Image Text Music (ITM), 15 Music is the most central word here. In this, she wants to go further than the French writer and semiotician Roland Barthes.

The latter’s Image Music Text is indeed Taylor’s biggest waymark. When one compares the table of contents of the two books, it’s clear Taylor fools around with the order of play from this 1977 book. Every small chapter starts with a quote from Barthes (called ‘RB’), parts of which are embodied and dissected by a protagonist called ‘C’ (Catherine herself?). RB himself turns up, now and then, transposed to ‘today’ somehow, sitting on a couch or lying in bed with C, for instance, having conversations ‘about the way meaning is made’ in itself.

Basically, this writer makes it loud and clear that one cannot, exactly fifty years later, completely rewrite Barthes, even if one wanted to. One needs to invent a language adequate to our experience and to history, she states. For sure, language wounds or seduces, as Barthes would have it, but syntax is always turning in an image again – or: has our bodies move through rooms. Music, therefore, is the ‘inescapable structure’ at the intersection of text and images that seduces us into ‘the activity of meaning-making’Id., 156. Our time calls for an approach to reading as 'an immersive synesthetic seeing-hearing-feeling ... and writing'. C is therefore viscerally living through or trying to catch up with the ‘sonic’ in photo spreads by Justine Kurland, Nan Goldin, or Robert Frank. Taylor refers to music as something that can get ‘lodged in a photograph’, ‘constantly speaking, but wordlessly – impossible to articulate in language, and yet, our longing to do so drives us wild’.Id., 89.

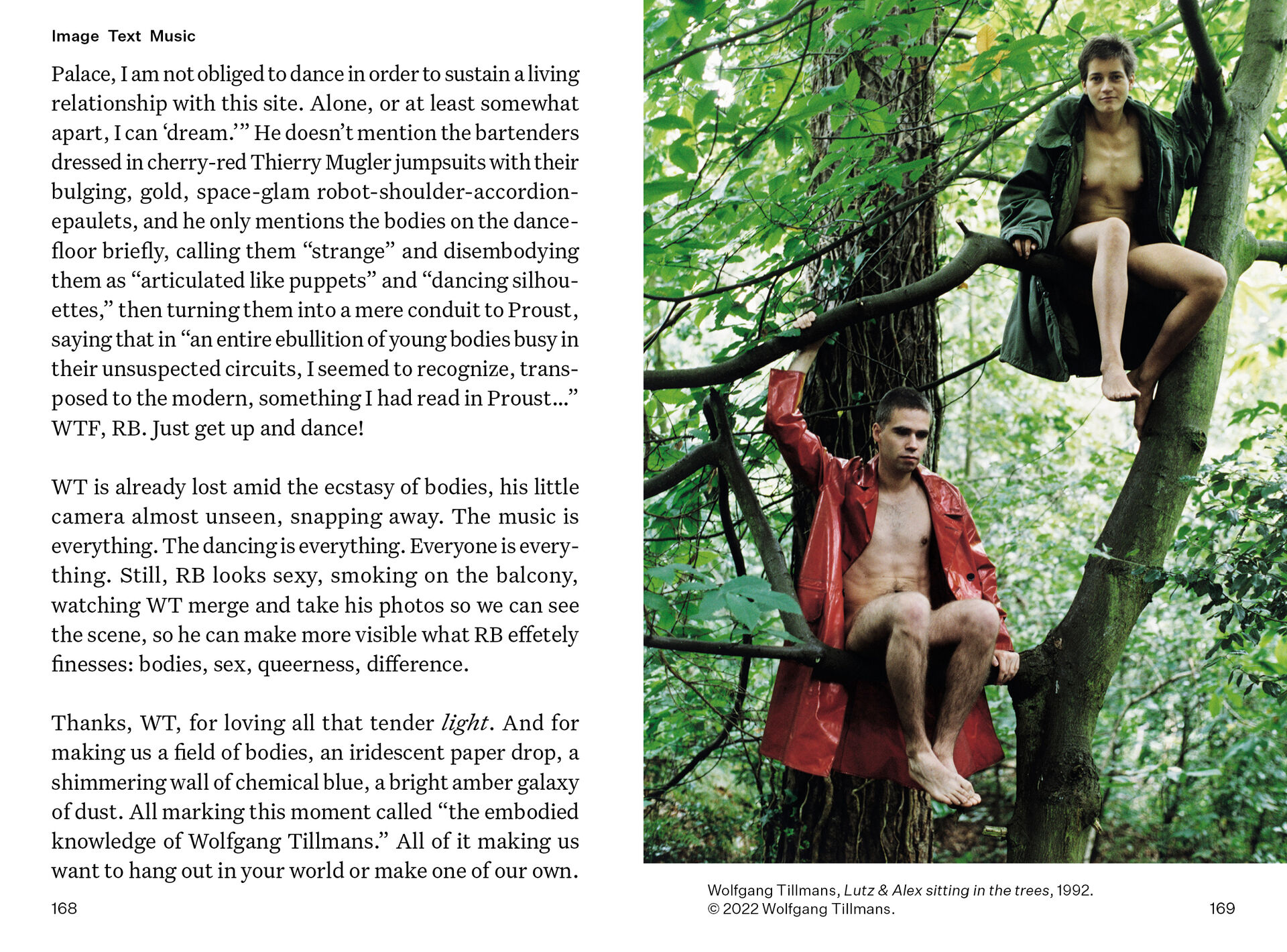

Where RB would have ‘the third meaning’ always maintain the erotic reverie, Taylor sees more relief in the image or story that ‘really pins and hits us’, that brings an end to that wanting, a radical suspension beyond reverie’s tipsy intoxications. Taylor eventually parts ways with RB in the last part of the book, despite having him flirting with Wolfgang Tillmans – a photographer whose work she believes embodies best ‘the grain of voice’ – in a bar.For all the ‘photographers’ she mentions, she clearly prefers, as she states explicitly on p. 52–53, ‘photographers whose work is like a language, whose pictures create a grammar, make a world to learn. Whose pictures don’t rely as much on the supplement of texts. In them, I see (and feel) again the signified of home and its penetration by the world – family, art, society – especially in pictures that rely on questions about spaces and bodies, their representations and their politics: Nan Goldin, Deanna Lawson, Justine Kurland, Nydia Blas, Malick Sidibé, Wolgang Tillmans.’ If only the two could have been lovers: merged together, they would create ‘a field of bodies’ that would give a real sense of purpose. But no, while thanking him for many things, she lets go of RB in a three-sentence chapter with the obvious title ‘The Death of the Author’, which turned into the latter’s most influential epithet indeed. She could have ‘cancelled’ him, but she’s clearly not. She even calls him a ‘sister’ITM, 12. .

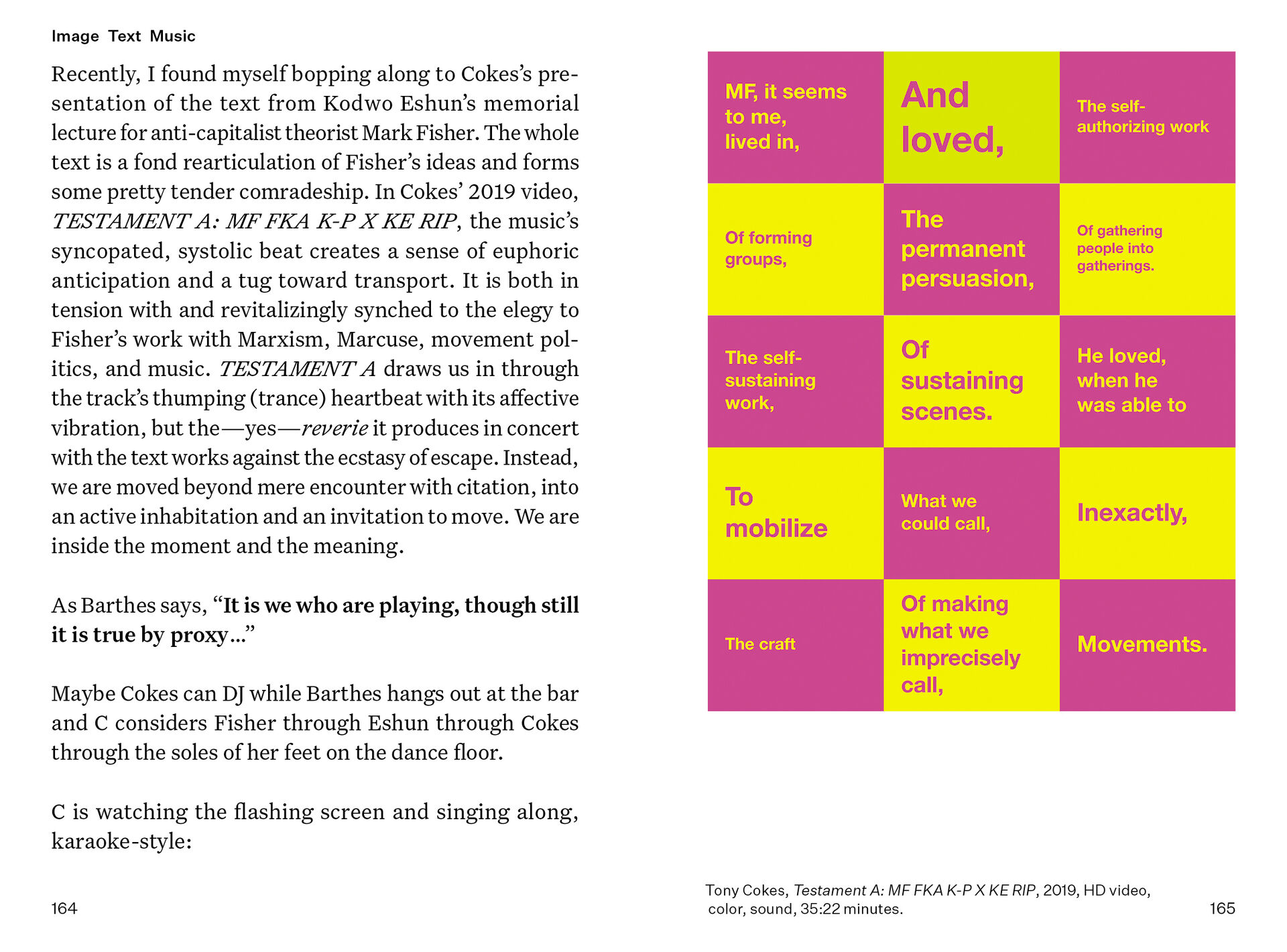

Taylor never intended to comply with RB’s desire for multiplicities and indeterminacy of meaning in the first place. While saying yes to frictions, breaks, and discontinuities, she says no to themes that are merely ‘combined, not developed’, as RB stated.This comes to life when she discusses Sara Cwynar’s ‘perversely gorgeous, sad and layered accumulations in her image-text-y videos’. While her work is visually stimulating in the way it merges images and texts, it also fails to deliver a clear message – something Taylor thinks is crucial, as she believes there should always be something to ‘learn’, ‘some real sorrow, rage, some outrage, if not insight’. Cwynar’s ‘mere citation’, as she calls it, both on the level of the images and in the way she pours a list of thinkers over us, ‘as if they were only images, too’, is hardly ‘moving’ us anywhere. Without using that word, Taylor lays bare in a pulsating, hybrid rhythm what’s so ‘instructional’I refer here to the previous book in the SPBH series, Carmen Winant’s Instructional Photography (Learning How To Live Now), published in 2021. in ‘photo-epigrams’, starting with Robert Frank and, later in the book, going from Brecht, of course, to Claudia Rankine to Tony Cokes (via Martha Rosler). They make tangible that ‘a life of hope’ITM, 112. involves – referring to Cokes’ video TESTAMENT A (2029) – being ‘moved beyond mere encounter with citation, into an active inhabitation and an invitation to move. We are inside the moment and the meaning.’Id., 164.

What I like about Taylor’s book is not so much the fact that you could get drunk on all the visual-textual references (attesting to her sisterly love for RB), but the fact that a lot of photographers today have positively sidestepped an old question: should the artistic, to be ‘meaningful’, be safeguarded from specific worlds or histories? Whether visual work is dependent on texts or not, it always relies on, and therefore always represents, a ‘translation’ of bodies, spaces, and worlds. Purposeful work makes clear the reasons behind our collective longing(s), how certain groups live, and what other subgroups strive for, always in relation to broader challenges. Many remain unafraid today to redefine what it means to ‘learn’ something through image-texts. In that sense, Image Text Music could be the perfect pre-text for moving us not only beyond old divisions between text and images, but also between education and art, and between individual and social responsibilities. That’s why Taylor lets C recognize (through Rankine) the ‘sonic power of poetry as well as pictorial and textual meditations – tableaux – to translate pain, to alter and alert, to enact a “responsibility to everyone in a social space”.’Id., 113.

Note to the reader. This article is part of Trigger’s 2023 ‘Summer Read’ series. We invited writers, researchers, photographers and curators to share what is currently occupying their mind through one publication they have been (re)reading during summer. What matters to them is now being recast as a challenge for today. Highly personal entries to a diversity of publications (photobooks, studies, monography, essay, historical research) lead us – readers of these readers – to reorient our gaze on (the history of) images and photography.