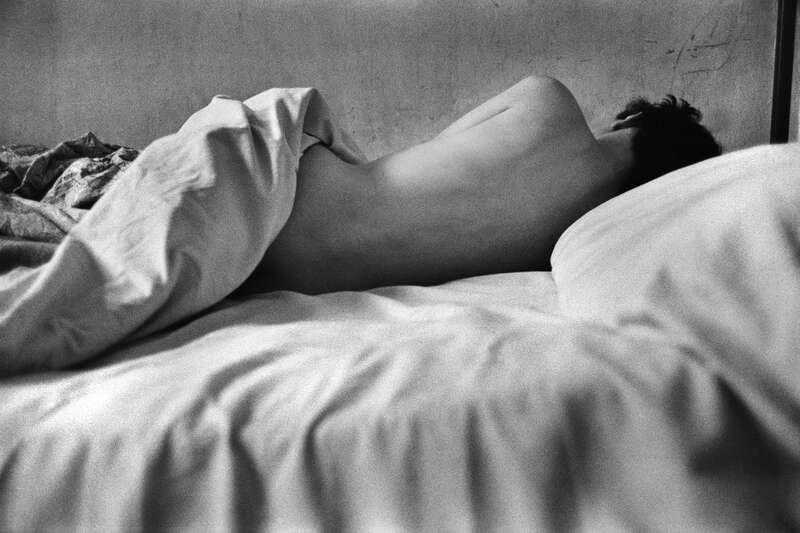

Hervé Guibert, Le fiancé II, 1982 Collection MEP, Paris. Don de Christine Guibert © Christine Guibert

‘In writing I have no brakes, no scruples, because it’s only me, practically, who is at stake, whereas in photography there are the bodies of others, relatives, friends, and I always have a little apprehension: am I not betraying them? I only do one thing: to show my love.’

So reads one of the wall texts in Love Songs: Photography and Intimacy, currently on show at the Maison européenne de la photographie. It comes from Hervé Guibert, who, as well as being an accomplished photographer, was a writer and a photography critic for Le Monde, known for texts such as À l’ami qui ne m’a pas sauvé la vie.Hervé Guibert, To the friend who did not save my life (Paris: Editions Gallimard, 1990). Whether in writing or images, Guibert often focused on the personal and the autobiographical, and, because he was gay and contracted AIDS, he busted taboos in doing so. The MEP show includes his intimate images of his partner Thierry, who he described as ‘the absolute boy of my dreams’ and ‘the main character of the main story’. Guibert’s books included thinly veiled characterisations of real people, such as his close friend Michel Foucault, a model for the character Muzil in A l’ami.

Guibert’s quote sets up a connection between intimate writing and photography as well as an invitation to compare and contrast the two, and that connection – and invitation – is also suggested more widely by the show. The curator, MEP director Simon Baker, proposes Love Songs as an alternative history of photography that focuses on intimate images, and in doing so, considers work that may be subjective; in his catalogue essay, he cites literary texts by way of example – writing that emphasises the autobiographical, the personal, and the unreliable. He references André Breton’s ‘“real-life” romance Nadja’ and its insights into love’s power to transform objects, for example, and describes the confessional Japanese I-novel, or shishōsetsu.Simon Baker, ‘Love Songs: A New Objectivity’, in Love Songs: Photographies de l’intime (Paris: MEP/Atelier EXB, 2022), 4, exhibition catalogue. This text was originally published in French in the catalogue for Love Songs, but I’ve used Baker’s English text.

Nobuyoshi Araki, 7 juillet 1971 de la série Sentimental Journey, 1971 Collection MEP, Paris. Don de la société Dai Nippon Printing Co., Ltd. © Nobuyoshi Araki, courtoisie Taka Ishii Gallery

He also picks out Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita and the dubious narrator who one-sidedly tells its tale, stating that with Lolita, Nabokov ‘is offering a stark warning that desire changes both the way we see things and the ways in which things can be seen’.Baker, 6. Baker wonders how love might intersect with the ‘complicated relationship’ photography has had ‘with its apparent ability to document, record or capture the real world’.Baker, 2. He gives his essay the intriguing title Love Songs: A New Objectivity.Baker, 1.

And Baker isn’t making this stuff up – this link with intimate writing also made by some of the photographers in Love Songs. There’s the quote from Guibert, and then there’s Araki, who described the I-novel as the form ‘that comes closest to photography’;Nobuyoshi Araki’s photographic series: Sentimental Journey (1971) and Winter Journey (1989–1990). this quote is also picked out in a wall text, alongside Araki’s images of and about his wife. Work by photographic duo and real-life couple RongRong & inri is also in the show via a 2000 series titled Personal Letters. The lovers shot the images while together, and then, when forced to part, wrote messages on the prints and mailed them to each other.

Sally Mann shows images of her ailing husband, meanwhile, and titles one of the shots Speak, Memory, referencing Nabokov’s 1951 memoir of the same name. Her section also includes a wall quote referencing another memoir, Graham Greene’s 1971 autobiography A Sort of Life. ‘In this ardent heart there must also be a splinter of ice,’ she states, just as Greene famously wrote that ‘there is a splinter of ice in the heart of a writer.’ And Nan Goldin’s diaristic series The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1973–1986) features in the MEP too; in a quote on the MoMA’s exhibition website, she describes the series as ‘the diary I let people read’.As quoted by MoMA, https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1651, accessed 7 July 2022. She’s also literally photographed herself writing in her journal.Nan Goldin, Self-Portrait Writing in Diary, photograph, 1989.

Two images: Nan Goldin, Nan and Brian in bed, New York City, 1983 Série The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, Collection MEP, Paris © Nan Goldin / courtoisie Marian Goodman Gallery

Photographic intimacy

It’s an intriguing connection, and beyond the MEP, other photographers and curators are exploring similar territory. Debmalya Ray Choudhuri is showing a series of images of himself, his friends, and his lovers at Rencontres d’Arles this summer, work that he thinks of in terms of a journal and that he’s named A Factless Autobiography, after the poet Fernando Pessoa. ‘Since he was a teenager, Debmalya Roy Choudhuri has been using photography as others use “I” in a diary’, writes his curator for Arles, Taous R. Dahmani, on the festival website. Choudhuri has titled another ongoing series The Mausoleum of Lovers, after the journal kept by Guibert.

Smiling Finally © Debmalya Ray Choudhuri

The Gaze. Home © Debmalya Ray Choudhuri

Two images: Image © Natasha Caruana from the series Muse on Muse / from the installation / VR piece Timely Tale

Meanwhile, British photographer Natasha Caruana has carved out a highly personal oeuvre over the last twenty-odd years, making work inspired by her experience of an affair with a married man, or love at first sight, or a relationship breakdown, among other topics. Her recent series, Muse on Muse (2021), which was shown at the Centre de la photographie de Mougins in autumn 2021 and Les arts au mur artothèque de Pessac in spring 2022, combines photographs, text, and video, and features intimate images of her husband, ex-boyfriend, and new-born daughter; it also includes nude self-portraits. In her description of Muse on Muse, Caruana concludes that ‘a raw intimacy is displayed, and in these final photographs, does the audience read them as fact and reflect on the story as truth? Or have they been voyeurs to some bizarre auto-fiction of an artists’ work?’

In fact, ‘autofiction’ has become a buzzword in literature, a whole genre combining fiction with elements of the author’s own life. The term was first coined in 1977 by French writer and literary theorist Serge Doubrovsky, but it’s popular again now. Guibert’s A l’ami qui ne m’a pas sauvé la vie was republished in English in 2020, while Emmanuel Carrère’s My Life as a Russian Novel: A Memoir, which includes candid descriptions of his girlfriend and love affairs, was published in 2007. My Struggle by Karl Ove Knausgård, a six-volume autobiographical novel, was published between 2009 and 2011.

Autofiction also has links with photography. The Festival du Regard in autumn 2021 was themed Intimacy and Autofictions, for example, and included Araki’s images of his wife; the festival offered ‘a dive into the heart of intimacy and autofiction’, stated artistic director Sylvie Hugues in the catalogue introduction, ‘by presenting authors who have taken their own lives as a common thread of their work.’Sylvie Hugues, 6ème édition du Festival du Regard (Paris: Filgranes Editions, 2021), 4, exhibition catalogue. My translation. She continues: ‘By approaching a form of narration, the “mis en scenes” of the intimate will become the photographic counterpart of what is called in literature “autofiction”. This ill-defined genre seemed interesting to us to compare with the notion of photographic intimacy.’Hugues, 5.

And autofiction has a closely related sibling, autotheory, which takes the essay and adds subjective and autobiographical material; it too has ties with photography. English author Olivia Laing has written both autofiction and autotheory, and has become a regular contributor to Aperture Magazine, for example; Paul B. Preciado, whose 2008 book Testo Junkie combines gender theory with his own experiences of taking the hormone, contributed an interview to the Transgalactic issue of The Eyes, published in January 2021. Meanwhile, Maggie Nelson’s 2015 book The Argonauts discusses her sex life, her transgender partner, her experience of motherhood, Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida, images by A.L. Steiner and Catherine Opie, and the ‘hetero-normative’ uses of family photography.

Nelson raises the concept of ‘radical intimacy’ when writing about Steiner’s work, in particular her image of a woman using a breast pump; for Nelson, this concept describes a particularly personal kind of image-making. ‘Photographers such as Goldin (or Ryan McGinley, or Richard Billingham, or Larry Clark, or Peter Hujar, or Zoe Strauss) often make us feel as though we have glimpsed something radically intimate by evoking danger, suffering, illness, nihilism, or abjection’, she states. ‘In Steiner’s intimate portrait of Childs, the proposed transmission of fluids is about nourishment. I almost can’t imagine.’Maggie Nelson, The Argonauts (London, UK: Melville House UK, 2016), 125. Note: the author has used the ebook version.

Nelson’s right of course – there are different kinds of intimacy, and image-makers and writers are currently exploring them all. There are Deana Lawson or Diana Markosian’s reworkings of family photographs, for example, and there are deeply personal books about the downsides of motherhood. But it’s intimacy between lovers that perhaps remains the most bracing and most personal, because public displays of sexual intimacy are taboo; the MEP show even comes with an online warning that ‘some photographs displayed in Love Songs can hurt the sensibilities of visitors, especially the youngest’. If regarding the pain of others raises questions about photography, as Susan Sontag proposed, perhaps regarding their pleasure does too.

Sontag picked out over-familiarisation as one of the pitfalls of images of suffering, and that’s something that comes up here. In his essay, Baker, like Nelson, uses the phrase ‘radical intimacy’, in his case to describe René Groebli’s images of his honeymoon;Baker, 3. later he adds that Groebli engages in ‘a kind of subversive “familiarisation”’.Baker, 4. Turning to Guibert, Baker states that the very private spaces, the bedrooms and bathrooms the French photographer records, ‘are special, however, not because we are normally excluded from them, but because they speak to us of a kind of normalcy which is exclusively the province of loved ones (whether families or lovers, but particularly lovers)’.Baker, 5.

Photography’s antidote

So why this contemporary interest in intimacy, both in new work and in older images and texts? It’s a huge question, but I asked Baker and he suggested the internet has made a difference, ‘because we’re all sharing more images on a daily basis’. I also asked Margot Wallard, whose explicit 2011 series Foreign Affair (made with her partner JH Engström) is on show at the MEP; she too suggested the internet, and the fact that it’s put images of sexual intimacy in front of a much broader audience. Maybe the internet has just made being familiar more familiar, both in what’s consumed and what’s shared, and if so, it’s easy to see how words and images might come to the fore. Both are eminently shareable, seemingly infinitely reproducible online.

From the book Distant Intimacy by Marie Dehe, published by APE 2022

Caruana’s work also suggests other ways in which technology is shifting our sense of intimacy. While making an installation about her mother, including a VR piece,Natasha Caruana, Timely Tale, installation series, 2017. she watched VR porn for tips on creating an immersive experience (the trick is using a single take). Her series Muse on Muse features screen shots, meanwhile, showing how her husband tracked her phone while she was out with her ex. Perhaps here it’s worth mentioning Marie Déhé’s new book, Distant Intimacy, which was shot entirely via webcams in the pandemic.Marie Déhé, Distant Intimacy (Ghent: Art Paper Editions, 2022). Showing Déhé and her subjects in states of undress, it suggests they’re alone together in a peculiarly contemporary way. An accompanying poem by Haydée Touitou is modelled on familiar online exchanges, opening, ‘I can’t see you / Can you see me / Wait’.Déhé, spread 149–150.

But perhaps artists and writers working with intimacy are shifting our conception of it in other ways too – exploring what is made public now, or pushing the boundaries, or both. Last year, artist, curator, and writer Lauren Fournier published a book titled Autotheory as Feminist Practice in Art, Writing and Criticism, which, according to the MIT Press website, is about ‘the autotheoretical turn’ and ‘signals the tenuousness of illusory separations between art and life, theory and practice, work and the self – divisions long blurred by feminist artists and scholars’. Maybe what’s at stake is a contemporary return to the 1970s expression ‘the personal is political’, the mindset in which one’s own experiences – including physical experiences – represent a challenge to social and cultural norms.

Preciado’s Testo Junkie is, in part, testament to the right to do what one wants with one’s own body, for example – a record of a lesbian love affair and the experience of gender transition (among other things); Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts includes similar issues. Olivia Laing’s most recent book, Everybody: A Book About Freedom, considers the body as a site of liberation. For all three, being open about sexuality is part of a wider emancipation. ‘I told you I wanted to live in a world in which the antidote to shame is not honor, but honesty’, writes Nelson in The Argonauts.Nelson, 44.

On this view, being behind closed doors can mean being stuck in the closet, and speaking up can therefore be an antidote; if so, it’s easy to see why photography seems pertinent. A medium that has been critiqued as a tool of the dominant, used to organise ‘types’ and with them hierarchies of power, it also has the power to do the opposite – to record the particular and the specific, which might well include the exception and the that-which-defies-convention.

It’s a reading Preciado voiced in his interview in The Eyes. ‘If the history of political resistance were to be told through photography, on the one hand, the entire history of psychopathological, criminological and colonial photography should be told – a history that begins with the first forensic photographic devices and runs through contemporary surveillance cameras’, he states. ‘And on the other hand, a history of photography as an artistic practice and instrument of gender and sexual subjectification that, from the 19th century to the 1980s, was essentially underground.’Paul B. Preciado, in conversation with SMITH & Piton, The Eyes, issue 11, 22 January 2021, 97.

This ‘subjectification’ plays out in Guibert and Goldin’s images, as well as in contemporary work. When I asked Choudhuri why he makes his diaristic images public, his reply emphasised the fact that he’s gay and from India, and the importance of speaking up. ‘It is easy to feel that intimacy is no longer a private affair, but it is critical, even more today to talk about it’, he stated. ‘Especially important for Black and Brown folx, and people from queer and trans identities, and those who I would say had been indoctrinated either systemically or through cultural institutions or through oppression to view sex and intimacy in a certain way.’

Wallard’s work with Engström can be interpreted in similar terms, a project that unabashedly presents female desire in a society in which it’s still minimised. Caruana’s work hits taboos around power and fidelity, why being ‘the other woman’ is a thing when being ‘the other man’ isn’t, and whether her husband ‘allows’ her to spend time with her ex. The Love Songs exhibition includes images by Lin Zhipeng that challenge conservative conventions in China – a country in which artists have long used the body as a site of resistance. Mann’s photographs of her ailing husband are a rare depiction of age and fragility in a culture that prioritises youth, virility, and power.

All three images: JH Engström & Margot Wallard, Série Foreign Affair, 2011 © JH Engström & Margot Wallard. Courtoisie galerie Jean-Kenta Gauthier, Paris.

The bodies of others

It’s an intriguing proposition, one that suggests Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida and its discussion of the personal image. Lauded since it was published in 1980, Camera Lucida seems weirdly apt again now, autotheoristic in its mix of the intimate and philosophical; in it, Barthes points to the singularity of the individual image, writing that ‘it is the absolute Particular, the sovereign Contingency, matte and somehow stupid, the This (this photograph, and not Photography), in short, what Lacan calls the Tuche, the Occasion, the Encounter, the Real, in its indefatigable expression’.Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida (London, UK: Vintage Classics, 2000), 4. Later, he adds that ‘this fatality (no photograph without something or someone) involves Photography in the vast disorder of objects – of all the objects in the world’.Barthes, 6.

Barthes sounds critical, but in the contemporary understanding, perhaps, this singularity is reinterpreted as a positive, as a way to preserve idiosyncrasies. Steiner’s photographic series Puppies and Babies ‘presents queer family making as an umbrella category’, writes Nelson, under which there are many variations rather than one right or wrong way.Nelson, 94. Nelson concludes this section by writing that ‘no one set of practices or relations has the monopoly on the so-called radical, or the so-called normative’.Nelson, 94.

This idea also suggests something more negative, though – namely, that no alternative history of photography can be fully representative, because it can never include the full gamut of possible relationships and permutations. Perhaps, too, it suggests a kind of atomisation, the impossibility of ever understanding another, because we can never see things entirely their way – no matter how many images they shoot, or how many volumes they add to their autobiography.

And public displays of affection raise other questions too. Nan Goldin questioned how The Ballad of Sexual Dependency could be considered voyeurism, Baker states in his catalogue essay – for how could she be a ‘voyeur of her own life’?Baker, 3.– but the voyeurism here applies to the viewer. Baker acknowledges this difference, writing that his alternative, intimate history of photography risks ‘setting artist and viewer at odds’.Baker, 3. This example also raises the spectre of commodification of oneself or one’s lovers or both – whether for money, or for the prestige of appearing in shows at, for example, the MEP. As such, they might be interpreted in terms of a capitalist or imperial gaze, an expression of a worldview in which everything is ripe for exploitation.

And in both cases, photography’s specificity perhaps opens it to more criticism than writing. Barthes writes that ‘photography cannot signify (aim at a generality) except by assuming a mask’;Baker, 34. words can. Intimate writing can be exceptionally specific – Carrère had a very public spat with his ex-wife over his book Yoga, and Guibert’s A l’ami was controversial for ‘outing’ Foucault’s AIDS status – but words themselves abstract. Baker has named his show Love Songs, suggesting the lyrics that thread through such ballads; he writes that putting the show together reminded him of making mix tapes, of ‘the sense of being immersed in the emotional landscapes of people we know (people we love) through the words, ideas and emotions of people we do not’.Baker, 8. I wonder if it’s as easy to feel this immersion with photographs, or if their specificity makes it easier to feel like a voyeur or to question the photographer’s motives.

Baker ends his essay by quoting the song Age of Consent by New Order, and the lyric ‘I’m not the kind that needs to tell you, just what you want me to’. The ‘you’ and ‘I’ here could refer to anyone, but images always show particular people. As Guibert states, in photography ‘there are the bodies of others’; this can be a strength and a power, but like him, I wonder if it also puts more at stake.