When I wake up in the morning and my girlfriend has already left for work, or if she has to travel, she leaves me notes. Small, yellow pieces of paper with red writing on them. Mostly things I have to remember, or other memories we cherish. I find them in different places around the house, but most of the time they are stuck to our bathroom mirror. After I’ve read the note, I collect it, with all the previous ones, inside a book about Canadian filmmaker Atom Egoyan.

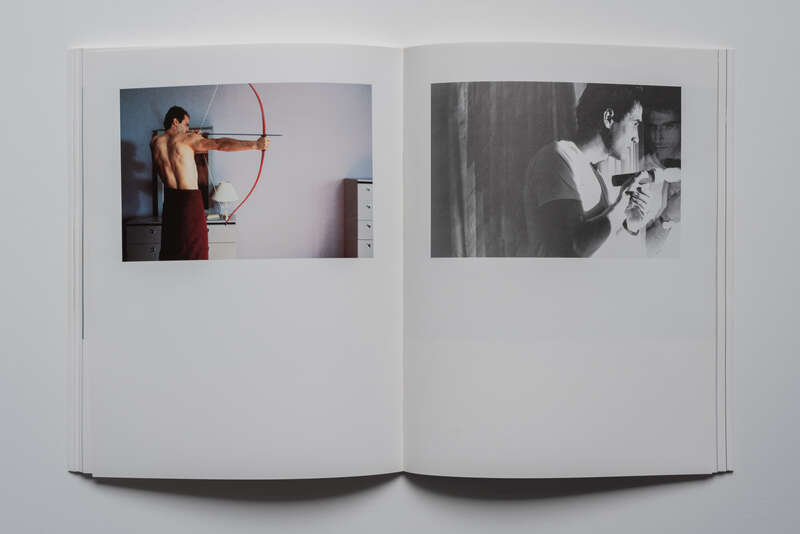

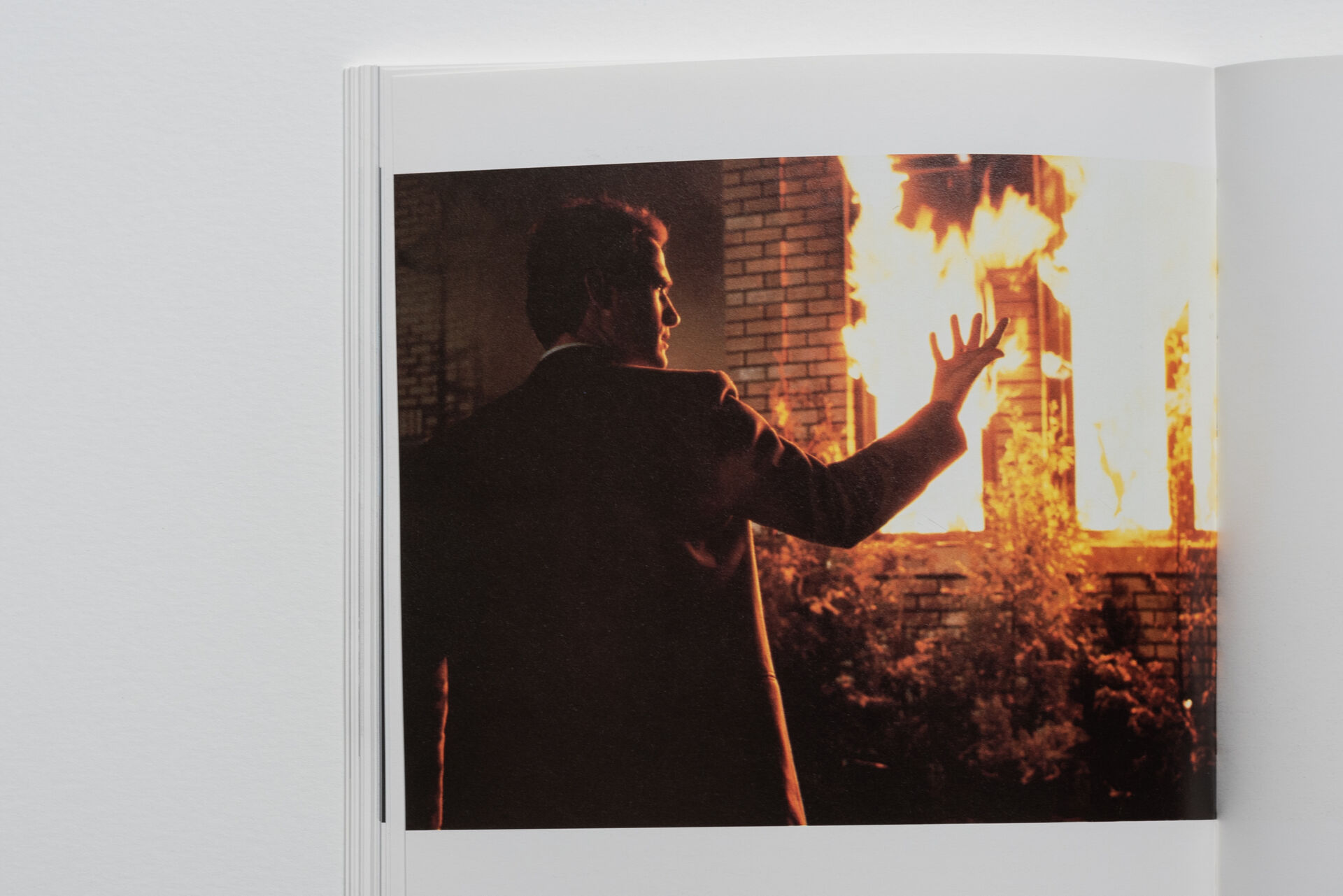

Notes among notes, that’s what they are. And what seemed to be a coincidence maybe isn’t one in hindsight: Egoyan would probably be fond of these notes too. When watching one of Egoyan’s films, you get the effect of searching through someone’s personal belongings. In The Adjuster (my personal favourite at the moment), rather than real images, the character Seta burns pictures of dwelling places. These arcane yet intimate fragments stare back at you, indifferent to the actors.

Atom Egoyan, Toronto, 2018 ©Matt Forsythe

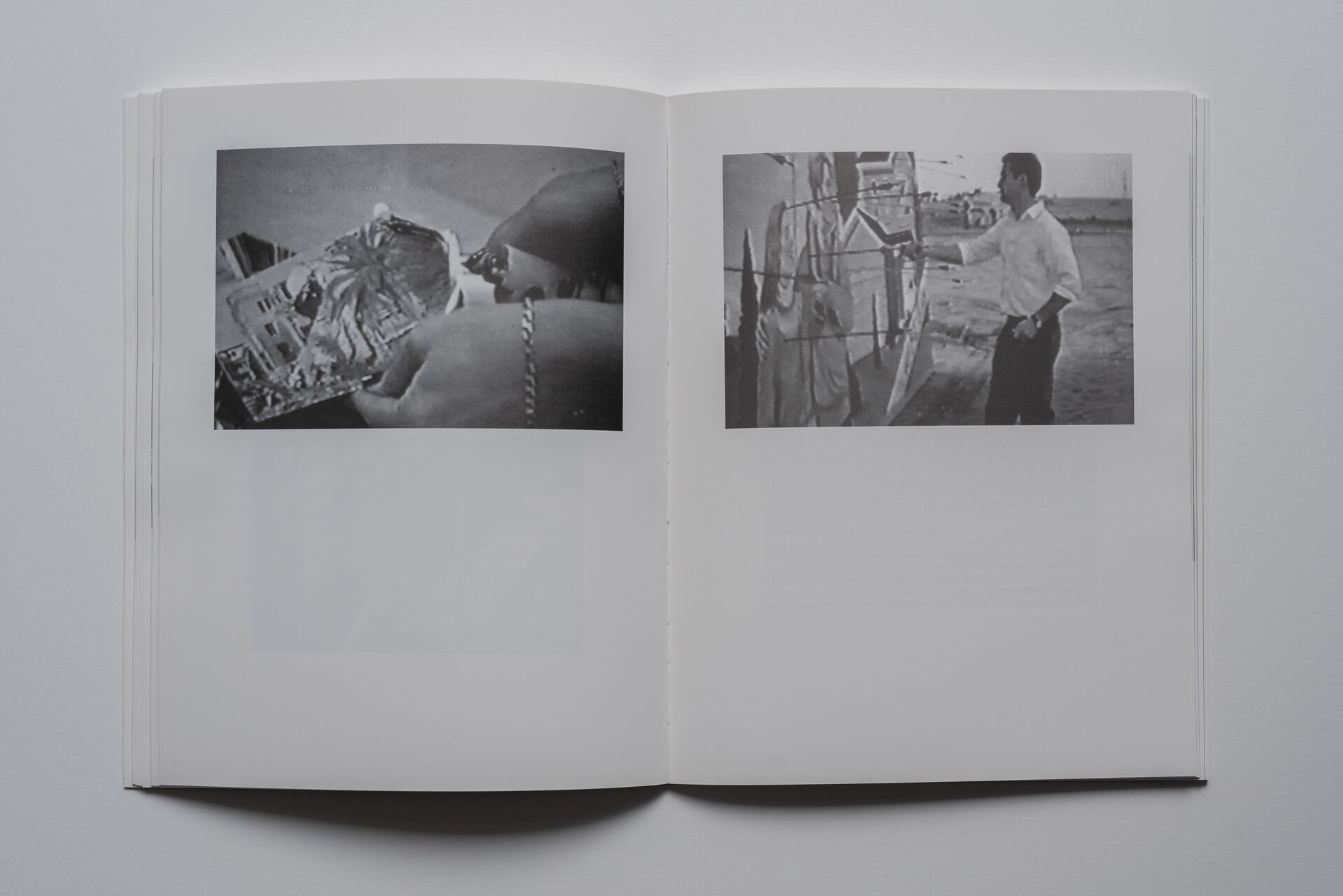

The book on Egoyan’s work is conceptualized just like that: a recollection of scattered parts. (The chapter by Jacinto Lageira is maybe the best entry.) You get insight into Atom’s filmography through multiple paused frames, grainy textures, and ruminations on how to spend time at home. Or at least that’s how I find myself reviewing his films this summer – not in a frontal way, but in profile. Through a mirror, I see associations that are far more quotidian, far more domestic and mystified. Which drives me back to another character – Chaykin’s Bubba – from the same film, reciting the following line: ‘So many places you see, you wouldn’t think twice about, they pass right through you. And then, for no reason, you can see a house, and find yourself wondering, “what is going on inside of those walls?”’

My personal associations within Egoyan’s work made me see not only how the film is no longer ‘in the film’ but around, through scattered objects – but also how scattered parts, looking back at us in different contexts, define our personalities. In a similar way, this publication tells us more about how Atom Egoyan’s films look back at us, through a diversity of angles, personalities, and texts.

Atom Egoyan is part of a series edited by Danielle Riviere, published thirty years ago, in October 1993 by Editions Dis Voir. The edition I have is translated from French to English by Brian Holmes.

Note to the reader. This article is part of Trigger’s 2023 ‘Summer Read’ series. We invited writers, researchers, photographers and curators to share what is currently occupying their mind through one publication they have been (re)reading during summer. What matters to them is now being recast as a challenge for today. Highly personal entries to a diversity of publications (photobooks, studies, monography, essay, historical research) lead us – readers of these readers – to reorient our gaze on (the history of) images and photography.