I’m still thinking

about some sweet summer plums

I ate in Italy last summer

known as nuns’ thighsFrancesca Woodman, diary entry, as cited in The Woodmans

Scott Willis’s 2010 documentary The Woodmans tells the story of, well, the Woodmans – Betty, George, Charles, and Francesca.The Woodmans, directed by C. Scott Willis (Kino Lorber: 2010), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bSKsA8gwSaM. All four worked as professional artists, and the film gives ample time to each of them, but all through the lens of Francesca. For anyone interested in learning more about the short but intense trajectory of Francesca, the documentary is a must. It showcases not only interviews with the family but also with classmates from the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), neighbours and childhood friends, and a colleague from Francesca’s brief and peripheral involvement in fashion after graduation, as well as fragments from her journals and sketchbooks. In an interview excerpted at the end of the film, Francesca’s father, George, says something I find very compelling when trying to understand her work: ‘All artmaking involves some psychic risk.’

This stood out to me for a couple of reasons. First, I totally agree that artmaking is inherently a psychic risk. It requires a great degree of independence, a willingness to confront and share one’s vulnerabilities, and an acute need to make meaning from one’s own life and experiences, all explored while pushing back against conventional social and aesthetic boundaries. There’s a long history of artists living through unique, risky, and precarious circumstances, but this can also contribute to art’s value: to truly understand our humanity we have to see its limits. Balinese artists sometimes give offerings to Saraswati, the Hindu goddess of knowledge and creativity, because they understand that one’s tools and experiences as an artist can either provide insight and a clear connection to divine energies or, just as easily, personal ruin.

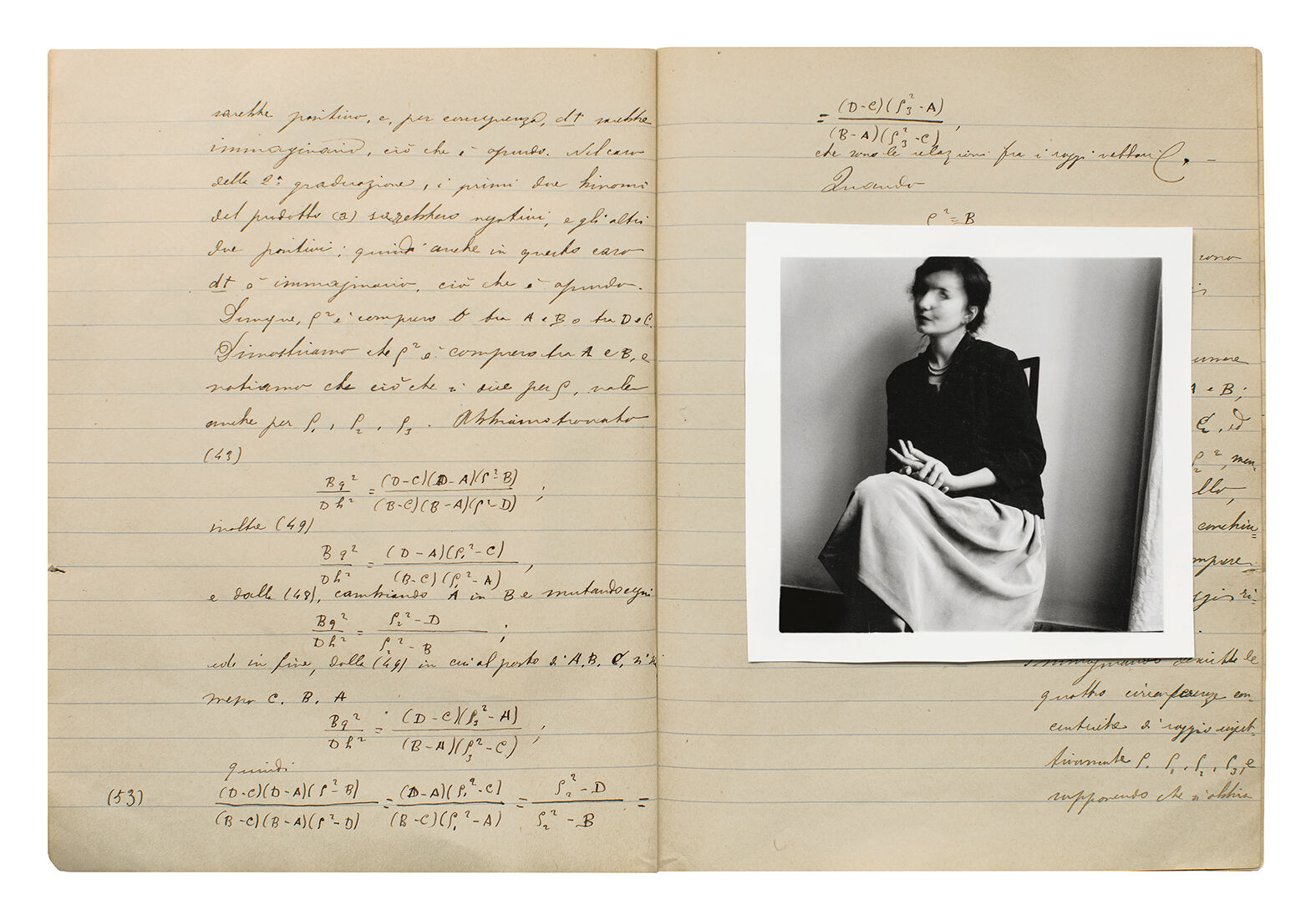

One of Francesca Woodman's first nudes. From: The Woodmans, directed by C. Scott Willis, 2010.

George’s comment also stood out to me because it so clearly defines what I find remarkable and problematic about Francesca’s unique and challenging oeuvre. I’ve always felt that her work is precisely about this psychic risk; from the beginning – dating back to when she was thirteen or fourteen, the age at which she is often cited as making her first ‘mature’ artworks – she walked a sharp edge, exposing herself as an artist, a free-spirited woman, and a deeply sensitive human being, using manic impulses and personal trauma to peel back layers of her psyche and expose a raw and primal core.

I watched The Woodmans after reading the newest MACK Books publication devoted to Francesca, Francesca Woodman: The Artist’s Books. Like any committed photographer and educator, I’ve been familiar with her work for decades, but I never really studied it. I knew that Francesca was from a family of artists – I worked at a prestigious ceramics college in Alfred, New York, and there Betty was more fashionable than Francesca – but The Woodmans helped me to see that differently. Born in Denver, Colorado, and raised in nearby Boulder, Francesca was immersed in an artist’s life from the beginning. Her mother, Betty, was an accomplished and influential ceramicist and provided a model for the personal discipline and sacrifice required of any artist. Her father, George, was an abstract painter and a professor at the University of Colorado in Boulder, which provided sabbaticals and academic freedom. The family home was filled with art made by Francesca’s parents and collected from friends. Francesca even did her second grade of school in Italy, where her parents provided deep exposure to art museums in Florence and Rome.

George gave Francesca her first camera when she was thirteen, right before she left home for boarding school at Abbot Academy in Massachusetts (now Andover Academy). She immediately took to the medium, and apparently had an exceptional middle school photography teacher who was able to nurture her interest from the beginning. Francesca’s first pictures were conventional, like any beginner’s, but she quickly discovered self-portraits and nudes, photographs that both her family and critics see as the true beginning of her work as an artist. As her interest in photography developed, these became her primary subjects, the pictures evolving into much more complex representations of personal and gender identities and sexuality.

There are a few other things discussed in The Woodmans that I feel are important to acknowledge when looking at Francesca’s work. Edwin Frank, a childhood friend from Boulder, talks about the summer of 1974, when a sixteen-year-old Francesca stayed in Boulder while her family went off to Italy; she instead spent the summer with a boyfriend whom Frank describes as ‘a good deal older than she’. A little bit later in the film, offered tangentially and with no clarification, Betty talks about a bad relationship that Francesca had a difficult time extricating herself from, telling us that for years she was with a man who was ‘not treating her well’. There is no further explanation of either of these relationships, or even any indication of whether they were the same one. I think today we have a better understanding of these things and have to ask, was this an abusive or manipulative relationship? If so, should that impact our understanding of the psychosexual performance enacted in Francesca’s photographs? If Edwin and Betty refer to the same relationship, these questions become so much more important. Also, in some of her excerpted interviews, RISD friend and classmate Sloan Rankin describes Francesca’s romantic and sexual life as ‘a sad situation’, noting incessant sexual attempts that were meant only as fodder for her work and her denial that sex had emotional meaning. Francesca’s exploration of sexual freedom isn’t necessarily problematic, but if her behaviours were an expression of pain or trauma from these relationships, questions should be asked. Regardless, given the sexual performance at the core of Francesca’s work, it feels much more important to me to address these kinds of ideas rather than, for example, to dissect the similarities between Francesca and Donald Judd and their understanding of corners, as UCLA art history professor George Baker did in a 2012 lecture at the Guggenheim Museum.George Baker, 'Through the Lens of Francesca Woodman,' (Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OM3uBw5_voY).

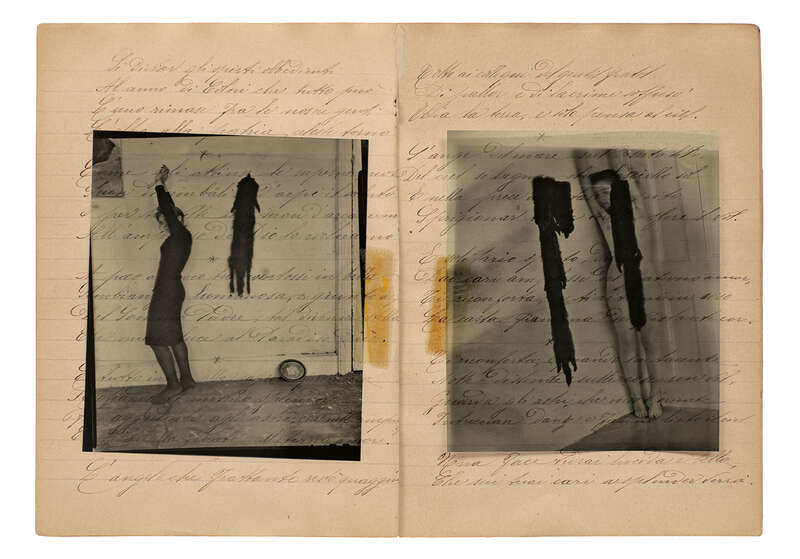

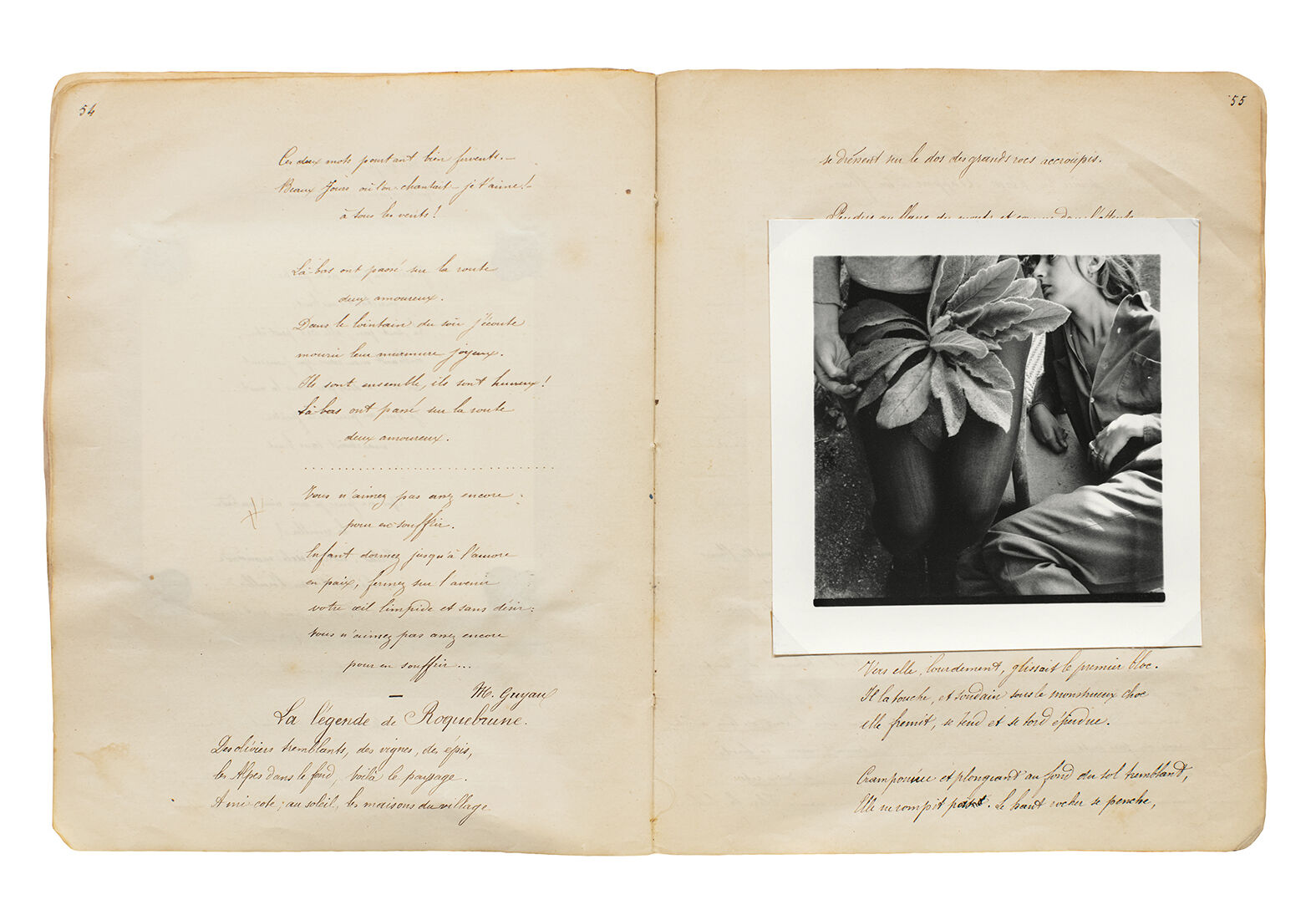

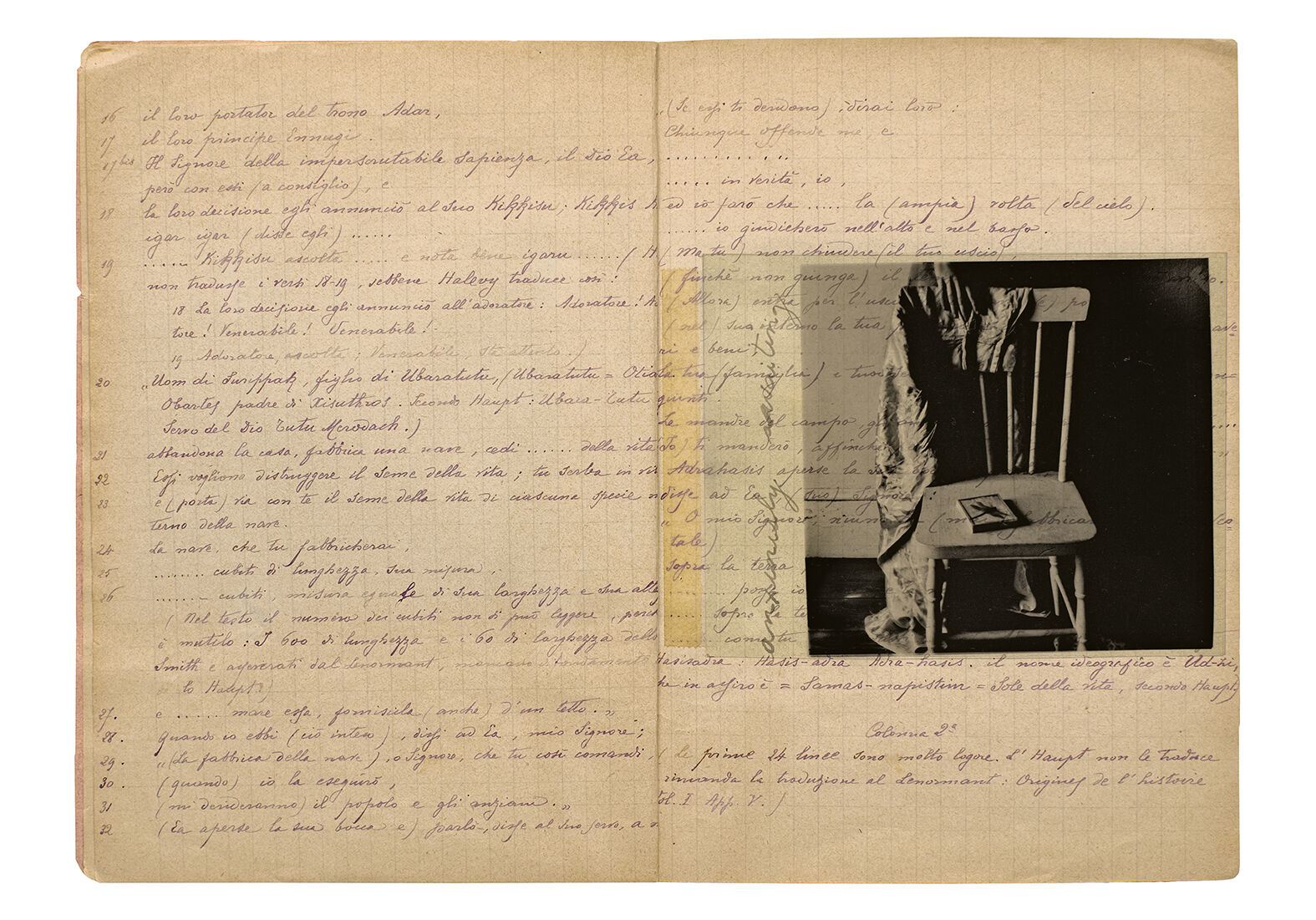

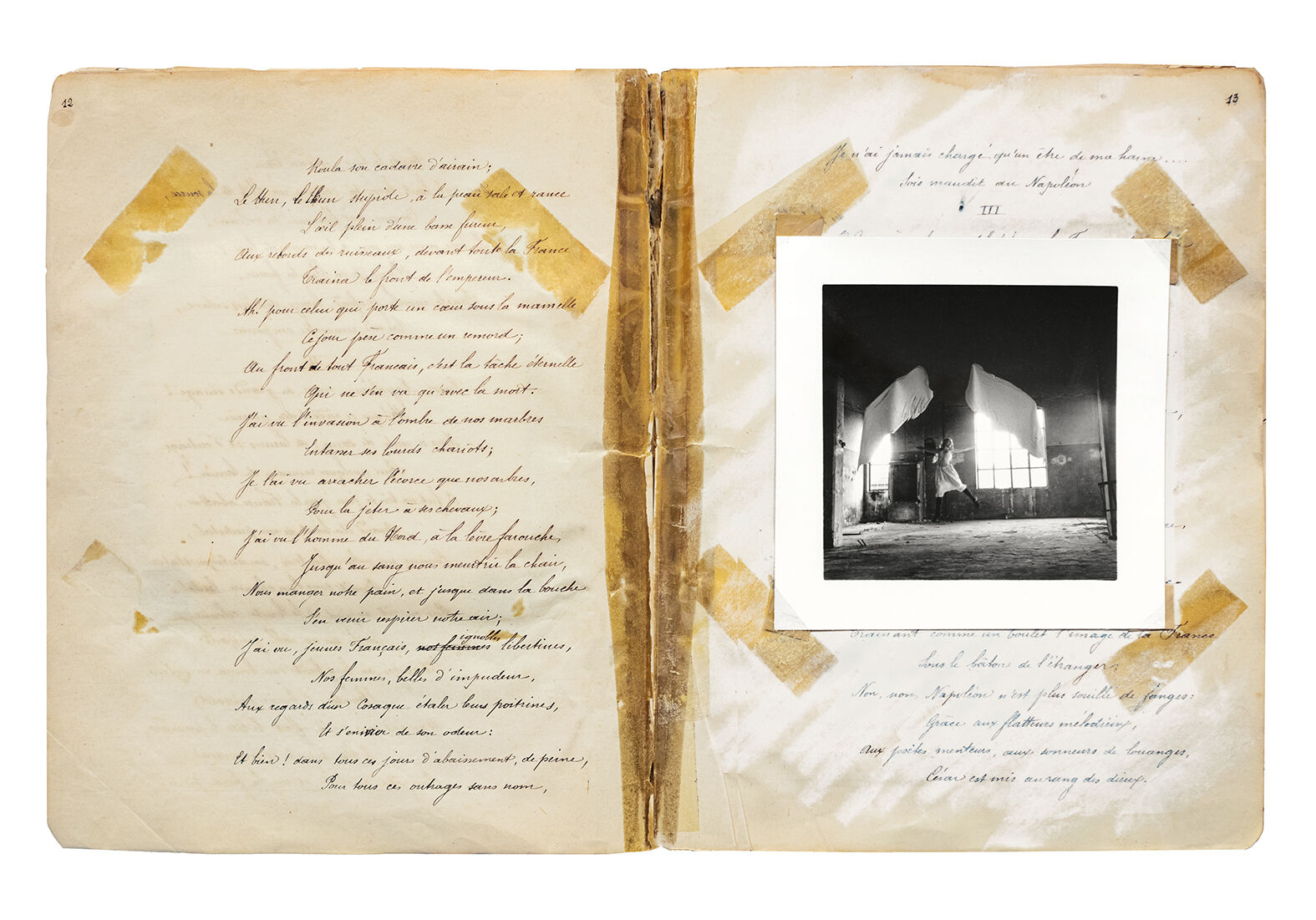

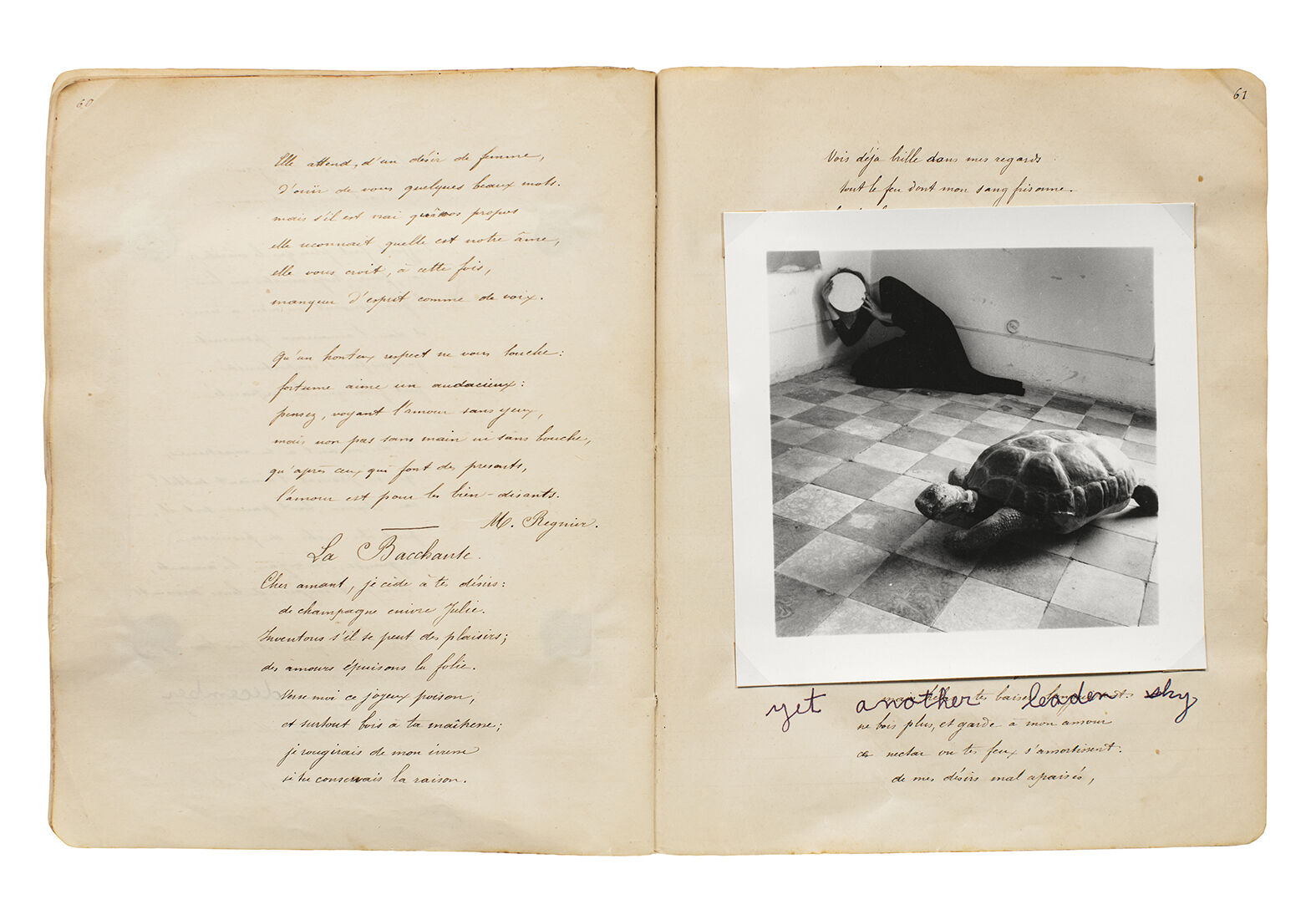

Francesca Woodman: The Artist’s Books offers the newest look at Francesca’s work and spawned my interest in reinvestigating it. The book is richly and beautifully designed, reproducing eight handmade books by Francesca, all made between 1976 and 1980 and each presented in its entirety (two for the first time). All but one of the books, Portrait of a Reputation, 1976–1977, she made by mounting her own photographs on pages of old books she found while attending the RISD honours program in Italy in 1977 to 1978. Portrait of a Reputation is simpler, with pictures mounted onto white paper, stitched together with a red ribbon. The books she appropriated were from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, all but one of them written in Italian. In developing these photobooks, she experimented with pasting both traditional darkroom prints and positive transparencies made on sheet film directly onto the pages, exploring different ways to see the text and photographs together. The Woodman Family Foundation, which acted as the editor of The Artist’s Books, offers simple but clear and important background information on each of the books reproduced and provides insight into how Francesca conceived of them based on her diaries and letters sent to family and friends.The Woodman Family Foundation was developed to secure and promote the artistic legacies of Betty, George, and Francesca Woodman: https://woodmanfoundation.org/. Apparently, Francesca liked to compare these books to André Breton’s collage novel Nadja, though also just the opposite; Francesca felt the pictures in Breton’s books were secondary, used haphazardly as springboards for the text narrative, and she reversed that strategy by making the text secondary (though still haphazard).

Given the number of monographs published of her photographs, a very small if amazing body of work, The Artist’s Books still managed to surprise me, even elevate my understanding of her work. American photographer Lewis Baltz is noted as saying that photobooks offer a narrow but deep space between novels and movies, an idea I’ve always loved, and one I think is aptly utilised in Francesca’s work. Flipping the pages of a picture book can have a stroboscopic effect, not quite the same as a film but still providing visual and narrative pace. Francesca used this beautifully. Anyone familiar with her work knows at least some of the pictures in the series On Being an Angel, but seeing them in The Artist’s Books I felt I was experiencing them for first time, understanding the flow Francesca created as deep lyrical and surrealist poetry. Beautifully designed by house designer Morgan Crowcroft-Brown, the MACK publication reproduces Francesca’s books one to one (except Untitled (Self-Deceit), 1978) and is as faithful to their original intent as possible. Each spread of The Artist’s Books illustrates a one-page spread from the originals. (The collector’s edition is actually a boxed set of facsimiles printed to look exactly like Francesca’s books.)

Francesca Woodman, The Artist's Books (London: MACK, 2023).

Generally speaking, there are two different schools of thought for interpreting Francesca’s output. One school sees her as a prodigy, an artist full of insight and ideas so much more mature than her years. The other school suggests that a tremendous amount of critical and historical interpretation is projected onto her work. In addressing John Szarkowski’s work on Eugène Atget, Abigail Solomon-Godeau argues that Atget was a function of modernism rather than a photographic visionary, telling us more about Szarkowski and the agenda of the Museum of Modern Art than the photographer.Abigail Solomon-Godeau, ‘Canon Fodder: Authoring Eugene Atget’, The Print Collector’s Newsletter 16, no. 6 (1986): 221–27. Available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/24552884. Some have offered similar readings of Francesca’s work, suggesting that criticism of her photographs often tells us more about the critic than an artist. Personally, I think both these schools of thought are correct. Given that Francesca was only twenty-two years old when she committed suicide, there’s no denying she was incredibly precocious and talented, depths equally matched by her relentless ambition. On the other hand, today we have a much better understanding of neuroscience, and could argue that her cognitive development may not have been mature enough to embody the ideas critics frequently attribute to her work (and thus George Baker loses me when he compares the critical framework of Woodman to Donald Judd, an artist who spent decades developing his ideas).

As an educator, I’ve had the remarkably difficult experience of coaching exceptionally talented young artists going through periods of intense trauma and emotional instability. I do feel quite strongly that art can be the best therapy for people in emotional crisis, but also understand that other therapies can be required too. How do you coach the work but also help them pull out of the damage they’re expressing? What is an educator’s ethical responsibility in seeing students make work like Larry Clark’s or Nan Goldin’s? To tell them, ‘Don’t do drugs or have psychic breakdowns’? In The Woodmans, Betty describes her understanding of Francesca’s work as strictly formal and not biographical, and classmates called her a ‘rock star’. I see her as precocious, ambitious, and independent, but I also see that she was making work like other young artists I’ve watched enacting trauma. And I find it incredible that no one close to her acknowledged this at all.

Indeed, I would say the real strength of Francesca’s work and its enduring quality lies with this idea of trauma. Woodman possessed an incredible aptitude for revealing her psyche before the camera, without any inhibition or restraint. More than that, however, somehow, miraculously, she was also able to explore an incredible drive for freedom, balancing her trauma with a reckless pursuit of transcendence. With unflinching abandon, she laid it out there for all of us to see, finding play and joy among her most broken pieces. If you agree with George that all artmaking involves some psychic risk, then Francesca was a psychic warrior, performing some kind of pagan dance that was at once an expression of freedom and an exorcism.