A way to preserve forgotten stories. To amplify and reclaim counternarratives. A form of healing, an intimacy. A way to position oneself, and a commitment towards social change. A space in which things can happen. ‘Doing art’ has multiple meanings to the emerging talent of MINO LAB, implying a great many questions: How can you invite someone to look differently? How do you root your work in the communities it emerges from – and how do you give back? How do you dedicate your creativity to where it is needed? And how do you sustain yourself while doing it?

Creating from a social engagement is an ongoing commitment that manifests in a multitude of ways in their diverse practices, but if one thing is clear to the dedicated young makers, it’s that you can’t do it on your own. And that a shared meal may help to digest the challenges that come with social art practices – to start a conversation.

In my notebook, I write down: ‘Collectivity’ and ‘Exchange’. Two thick lines under ‘Collectivity’.

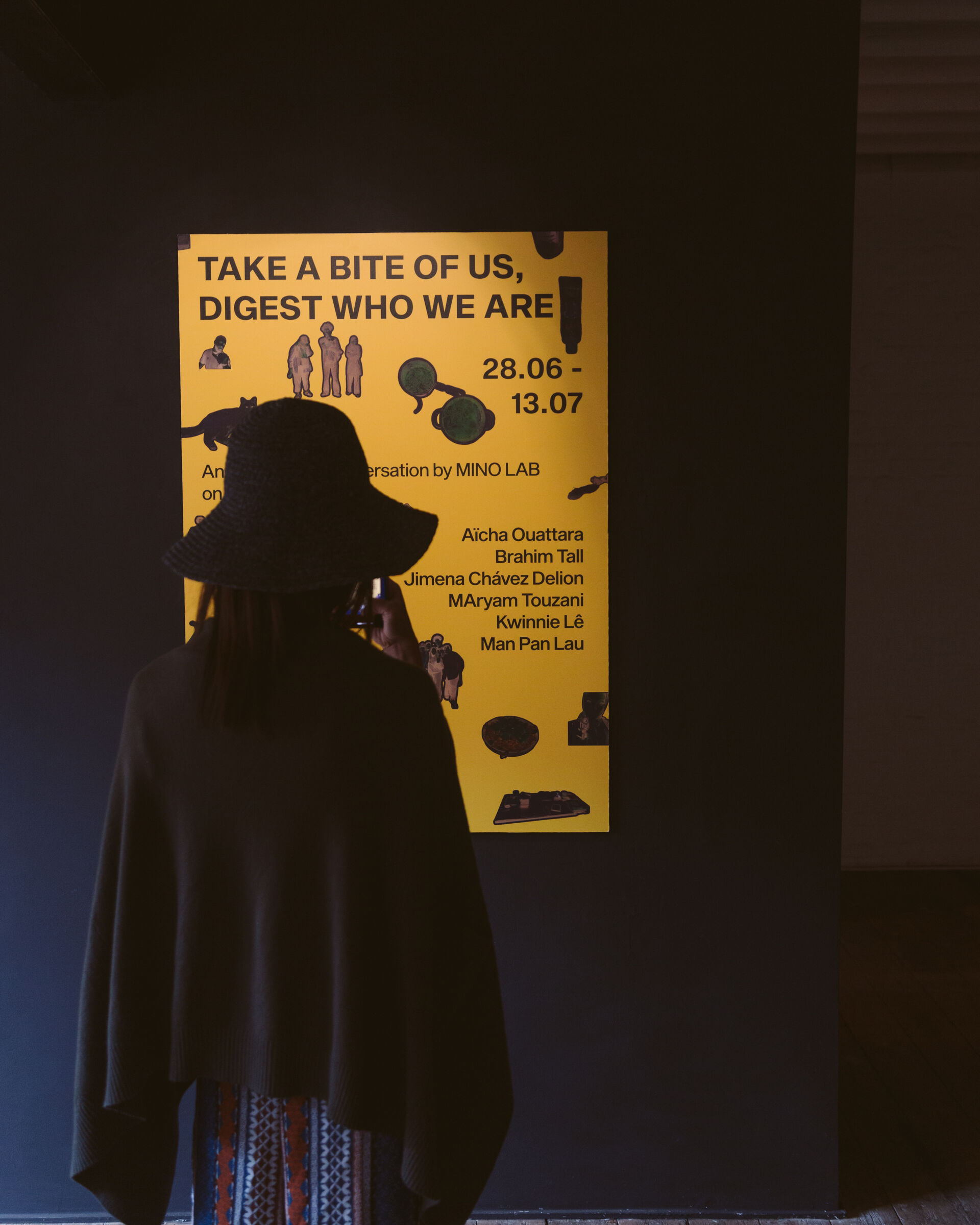

Two years ago, a message from Ama Koranteng-Kumi (image on the left, Ed.) popped up in my mailbox, asking me if I would be interested in exchanging thoughts on MINO, an art space she was co-founding with Tinne Langens, which would focus on underrepresented makers and community-building. A few months later, with MINO still taking its very first steps, we welcomed MINO’s first group of residents as part of the MINO LAB residency programme for social art practices. This year, MINO LAB once again selected a group of promising makers, consisting of multidisciplinary artist Aïcha Ouattara; Brahim Tall, a multidisciplinary artist with a background in photography; Peruvian multidisciplinary artist Jimena Chávez Delion; Rotterdam-based artist, researcher, and writer Kwinnie Lê; Lau Man Pan, a Tilburg-based visual artist from Hong Kong; and Rotterdam-based photographer MAryam Touzani.

I’m meeting with them on one of the hottest days at the end of summer, in the historic warehouse that is MINO, where, just weeks ago, their open studio exhibition Take A Bite of Us, Digest Who We Are opened. Looking back on their time at MINO, we sit down at MINO’s kitchen table – in line with the spirit of their exhibition, which centred around the table as a creative and communal space.

Joined by Reem Shilleh (artistic coach of MINO LAB 2024) and Tatjana Huong Henderieckx (production and coördination), Ama Koranteng-Kumi enters into a dialogue with the residents.

Ama: MINO LAB focuses on social art practices and change-making through artistic strategies, something that resonates with all your practices. What initially drew you to socially engaged work and, more specifically, to this residency?

Brahim: For me, it grew very organically. I studied photography at LUCA School of Arts to further develop my technical skills, but during my studies, I was introduced to different theoretical frameworks that very much coloured my work. If I look back at my earlier work, I can really see the evolution of how the Black body and bodily performances became a central element in my practice, something inherently tied to social and political engagement. After finishing my studies, it was difficult to find a space to ground. To me, MINO really provided this space, as well as the funding and the connections that are essential to the further development of my work.

Lau: I found the open call by accident, and it instantly spoke to me. I trained as a painter and always wondered about the social impact of images: How can they change someone’s view? What is the importance of exhibiting nowadays? And how can I communicate through my images? I was curious about exploring this further and looking for the time and space to do so.

Jimena: My main motivation, which is very much bound up with social engagement, is preservation. The preservation of memories, of things, of spaces, of forgotten stories from the margins and the general state of being marginalised. MINO immediately appealed to me because I was looking for a space that focused on socio-politically engaged work. I just arrived from Peru and felt quite lost, so I was very much looking for a community too.

Kwinnie: Looking at traditional tattooing practices as a form of dealing with colonial trauma, social engagement was always, quite organically, a part of my practice. Similar to what you’re saying, Jimena, I view my practice as a form of amplifying counternarratives and healing. Unfortunately, there isn’t a huge canon built around tattoo traditions and, most of the time, it’s situated in ethnographic research. I was, however, looking for a place where I could position my work as an artistic practice. This is precisely why MINO LAB spoke to me, as there doesn’t seem to be a lot of space for these very particular practices in other art institutes.

MAryam: Being confronted with social issues from an early age deeply impacted me. Rather than being something I actively searched for, photography organically became a tool to express and explore these issues. Driven by what I would call a ‘productive frustration’, I use my art to further question, understand, and communicate social issues and the themes related to them. When I saw the open call for MINO LAB, I recognised an opportunity to connect and create with makers who, while not necessarily sharing the exact same experiences, create from a similar place.

Aicha: In relation to social impact, I think it’s essential to position yourself in a way that isn’t disconnected from the world. I could be inspired by many different things, but I’m interested in thinking about how I can commit my creativity towards something that is needed. I was drawn to MINO LAB because I felt a lot of openness: I didn’t go to art school, but at MINO, I felt welcome to try things out. It gave me the trust and support I needed to further develop my research without the pressure of immediately producing something specific.

Ama: Could you walk us through your creative processes and how your time here has shaped your work?

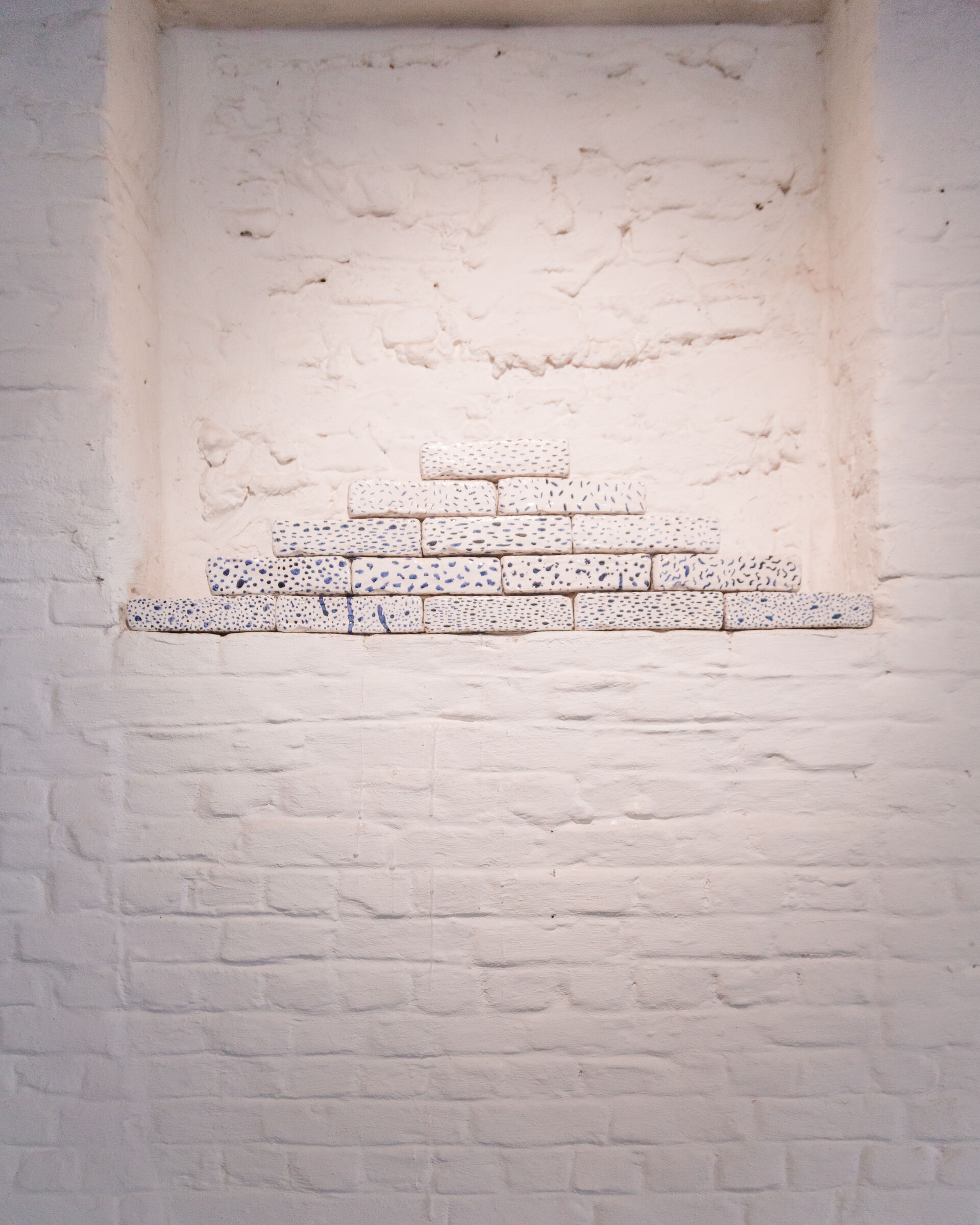

Jimena: I knew I wanted to work around my own experiences of migrating, with the feeling of nostalgia as a driving force. After a few months, I realised I mainly wanted to address ways of holding onto something. I started from very specific locations, such as my mum’s room or the house in Lima where I grew up. I searched for similarities between how I relate to these places and inhabiting the space at MINO. I had been writing a lot throughout the process, and during the residency, I mainly focused on translating my writings into something more tangible, mixing old and new ways of materialising my work.

Brahim: Initially, I did have quite a clear idea of what I wanted to explore during MINO LAB. Being here, however, I redirected my focus towards the group, asking myself: How can I feed the collective? How can I, while being here and absorbing a lot of things, also give back? I tried introducing things into the group that I’ve been researching in my own practice but that might benefit others too. In the final month, I was more focused on my own work, but this has, of course, been shaped in and through this exchange. Being open to what was happening around me and actively engaging with it really benefitted my own practice in a lot of ways.

MAryam: I absolutely agree. During this residency, our shared experience of cooking, talking, and learning allowed me to slow down and embrace a more reflective process. As a photographer, my usual approach is active and often solitary. But the residency transformed that rhythm, offering a collaborative environment that encouraged patience, listening, and connection. This shift has given me a new appreciation for the value of slowing down and creating alongside others.

Kwinnie: In my experience, residencies tend to be a rather solitary experience, but MINO LAB was quite the opposite. We learned a lot from each other, and I found it very insightful to see how everyone deals with the challenges that their particular practice poses. The exchange during the masterclasses was very valuable too – talking to people who’ve been in a similar field for a much longer time really broadens your perspective.

Aïcha: Absolutely. While being here, I somehow found ways of accessing my initial ideas through different doors – approaches I otherwise wouldn’t have thought of. The masterclasses and the people we’ve met throughout the residency played an important part in (re)directing my research. A big shift in my creative process was inspired by our visit to Dodi Espinosa’s studio,The Antwerp-based multidisciplinary artist Dodi Espinosa (Mexico City, °1985) coached the first cohort of MINO LAB residents in 2022 and kindly welcomed this year’s residents into his studio. who introduced me to new materials and provided me with the tools and methodologies to approach them.

AMA: How do you define the role of art in addressing social issues? And what challenges do you encounter in doing so?

MAryam: I think the potential of art in addressing social issues is deeply rooted in vulnerability – in the sense that being open and vulnerable is essential in authentically engaging with these issues and connecting with others. The challenge here is, of course, that this requires a continuous process of critical self-evaluation.

Aïcha: We all have a certain intimacy with very different things. I think art can create a space in which we can value that intimacy, try to understand it, and put it at the service of change.

Lau: I think of art as a tool, or a facilitator. A way of providing a structure in which something can happen.

Jimena: And it was very valuable to see examples of how different art spaces relate to the idea of social art practices – which structures there are.

Kwinnie: Something that came up a lot in our conversations was the issue of a certain ‘art bubble’. Being afraid that, while you’re trying to bring about change, you’re only talking to the same people over and over again, from a comfortable place.

Brahim: Yes, and at the same time, sustaining yourself is really hard. Finding ways to monetise your work and professionalise your practice takes away a lot of the spontaneity and freedom, but it’s often presented as the only way. It disregards a lot of what art is about and erases alternative economies and forms of exchange. Throughout our field trip to Amsterdam, it became very clear that there’s a big gap between the professionalised ‘real’ art world and these squats or other places where people ‘do’ art in very different ways that aren’t recognised by bigger institutes. And they don’t seem to merge.

Aïcha: Exactly. And this very much relates to what Kwinnie said: if you’re depending on this particular bubble to sustain yourself, you get trapped. It’s not easy to have a real impact and, at the same time, be able to support yourself. If it’s really about impact, then you might have to take more risks or work in ways that might not be subsidised or supported by bigger institutes.

Ama: When we talk about social art practices, we often talk about community – in a very different sense than the so-called ‘art bubble’ you mention. What strategies, be they aesthetic, conceptual, or collaborative, do you use to engage with different communities, outside of MINO too?

Kwinnie: Working with traditional tattoo traditions, I mainly relate to the specific communities built around these practices. I’ve collaborated with other traditional tattoo practitioners who are embedded in a broader community, but I’m still trying to figure out what it means to, more specifically, revive these traditions in Vietnamese communities.

Aïcha: It’s really all about collaborative strategies. As I don’t have a formal arts education, I rely on a community of friends and their experiences and knowledge to be introduced to certain spaces and to know how to navigate them – or to have the tools to write a grant application, for example. It’s through these communities that I’m able to further evolve, both as a person and an artist.

Jimena: For me it’s quite similar. The notion of ‘community’ is not necessarily visibly translated into my work, but being a Peruvian artist in Europe, it’s imperative to build a community, sharing tools with other Latin American artists about different ways of sustaining yourself and your practices.

Brahim: It’s not always a very obvious thing. I just don’t see my practice as existing in a vacuum: you pick up things along the way that inevitably infiltrate your practice, which is, in this way, organically connected to a community.

Ama: In sharing this space and collaborating, what have you found and what do you take with you towards future projects and challenges?

Aïcha: I very much value how MINO Lab gave us the time and space to just ‘be’ together. It wasn’t just about producing as much or as fast as possible. Sharing meals was a big part of that, too.

I was also really inspired by the garden community at MINO. Meeting the people behind it and interacting with the space opened up new ways of thinking about bringing together artistic practices and permaculture initiatives.

Brahim: I agree with Aïcha: finding a space to slow down, to ground oneself, and to give certain projects the time and space they need was very meaningful. From the beginning, we could shape the residency to fit our own needs, resulting in a lovely feedback loop: we were shaping the residency while it was shaping us.

For me, going to Amsterdam and seeing all these different kinds of art spaces further developed my own view of the art world. It gave me a more graspable overview of the possibilities, once again opening up the question of where to position myself as an artist.

Lau: I recognise what you say about shaping and being shaped: I learned a lot from all of you. I was inspired by a lot of different approaches and tried to pick up something from all of them, trying to merge it with my practice, making it my own. The same goes for the masterclasses and all the people we have met during our time here: the exchanges that grew out of sharing a particular time and space were extremely valuable.

MAryam: I very much agree: after graduating, the importance of community became even more clear to me — not only as an environment in which I develop my own work, but as a shared creative space in which my work resonates with the practices of others. This particular collectivity is something I really valued in MINO LAB. Looking ahead, I hope to keep contributing to communities who amplify marginalised voices, foster dialogue on migration, and reclaim underexposed stories.

Jimena: MINO Lab allowed me to work on projects that I had put on hold due to a lack of time or means. This openness was very important to me, and something we touched upon earlier: finding ways to sustain yourself. And I have learned a lot from all of you in that regard, providing me with better tools to navigate the Belgian context too. Like MAryam says, having this small community was truly meaningful. I haven’t had the chance to do a lot of collaborations in Belgium and I would love to explore this collectivity more in future projects.

Kwinnie: This collectivity was undoubtedly central to my experience here. In meeting people, talking to them and having the time to do that, I learned a lot of very concrete things. For example, when I was struggling with the element of participation in my performance, talking to Va-Bene really helped me to further develop this aspect of my practice. I think it’s also very important to mention Reem being our guide during our time here. She’s been extremely valuable throughout our process.

Reem: It has been transformative for me too. It truly was an exchange. And I think the togetherness you are referring to, and the consequent exchange, were very present in the exhibition concluding the residency. To me, it really embodied the collectivity we were trying to cultivate: you could tell that a lot of attention was paid to how different works relate to each other, and how they enter into dialogue. Having a large dinner table as the centrepiece seemed only fitting, inviting everyone into this exchange, creating a platform where everyone could present their work, and gathering around it.

Brahim: Yes. A very big part of the commitment towards this residency was learning to listen to others, becoming part of their process, understanding what other people bring to the table. Finding a common ground throughout this exchange and being able to create something together really is a testimony to this commitment.

Reem: Like every single meal we made together.

Partners

-

MINO is an Antwerp-based independent art and community space, strongly situated at the intersection of arts and society. Since January 2022, MINO has striven to create opportunities and visibility for emerging multidisciplinary artists, centring underrepresented voices and alternative narratives without aiming to institutionalise them. MINO thus actively positions itself in a fertile in-betweenness, with the objective of building an inclusive and socially engaged environment through socially motivated projects and practices by trained as well as autodidact makers. In doing so, MINO is committed to providing emerging artists with the support to professionalise their practice while consciously rooting it in the communities it grows out of. With community-building as a core value, MINO houses a multiplicity of projects, including MINO agency, which provides inclusion training and expertise to different (cultural) organisations; MINO’s lively rooftop garden; and a wide array of events such as exhibitions, talks, workshops, and nightlife.

Central to MINO’s ongoing engagement in supporting emerging makers whose practices are situated between grassroots and institutionalised contexts, is its talent-development programme, MINO LAB. MINO LAB is an annual residency for emerging talent, focusing on social art practices. Exploring the potential of aesthetic strategies for changemaking, the programme provides six multidisciplinary artists with the space, time, expertise, and budget to further develop their work. For a period of three months, the residents are intensively coached and take part in a series of masterclasses and field trips. They are invited to critically reflect upon their own practices, grounding them in a broader socio-political context. The residency concludes with a final, self-curated exhibition at MINO.