‘The story begins on ground level, with footsteps. They are myriad, but do not compose a series....Their swarming mass is an innumerable collection of singularities. Their intertwined paths give their shape to spaces. They weave places together.’Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), 97. - Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life

Cody and Raylen, 2020.

Andy Richter had to get out of the house. He’d been cooped up by the pandemic, cut off from the travel assignments that had previously provided much of his work. He had a three-year-old son, Julien, whose early years were being shaped by the social deprivation of lockdown. And he had been engaged in a project – a photographic exploration of where he lived – that took on new urgency as the pandemic raised or foregrounded questions about community and care.

So he took his son and his camera and went out to walk the streets of Northeast, their Minneapolis neighbourhood. As they walked, with Julien sometimes lagging behind, sometimes running off ahead, Richter began noticing his neighbourhood in a way he hadn’t before. Some of that was the simple awareness of being there – being fully present in a place that he’d often merely passed through on the way to somewhere else. Some of it was the awareness that came from having a three-year-old in tow: there were busy streets to cross, dogs to meet, odd sights to absorb, a child’s wonder and attention to honour. But there was another level of awareness in Richter’s walking – and the pictures he’s made in this sprawling body of work most vividly engage with this level – of the meaning of place, the nature of civic engagement, and the complexities of raising a boy in a country struggling with the meaning and nature of both masculinity and citizenship.

The pictures in Walking with Julien document, demonstrate, and enact concentric experiences of world-making. They document the built world of Richter’s neighbourhood, making a kind of portrait of a place and the people in it. They also envision the incorporation of that world into the body and imagination of Richter’s son, whose explorations demonstrate the experience Gary Snyder describes when he writes that ‘we learn a place... as children, on foot and with imagination. Place and the scale of space must be measured against our bodies and their capabilities.’Gary Snyder, The Practice of the Wild (Berkeley: Counterpoint Press, 1990), 105. And the pictures build a world as a novel might, a semi-fictional world we engage with as a kind of intermediate reality, imagining ourselves walking with Julien through the neighbourhood the images create.

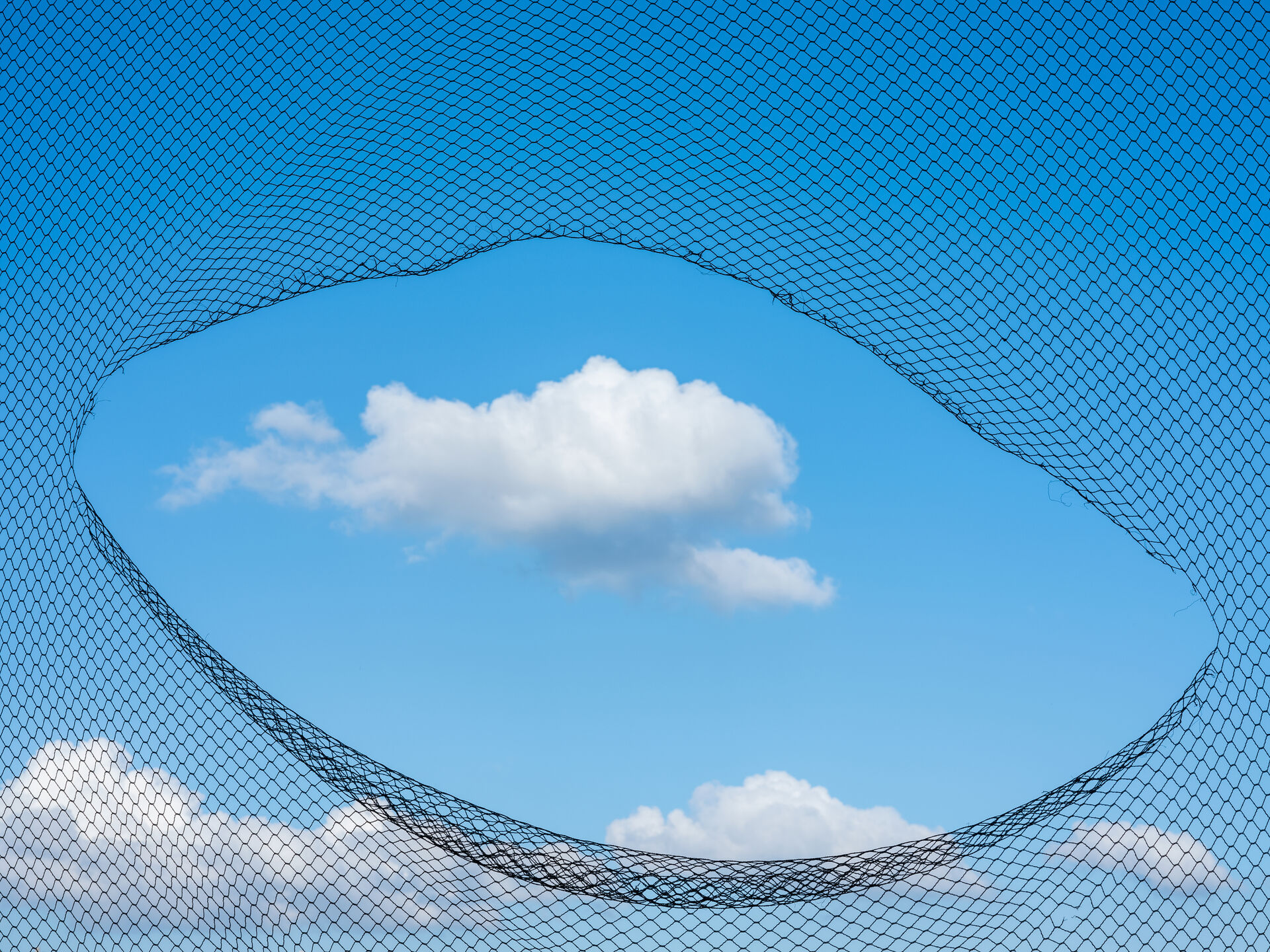

Portal, 2021.

Richter’s neighbourhood is diverse in both population and topography. In his pictures, we meet a range of characters – a young woman in a date-night dress, holding flowers and looking at her phone; a young man in a thobe sitting lightly against a wall, looking into the camera. There are windfall apples scattered on a patch of grass and a wind-blasted railroad crossing in winter; a shady creek and a burned-out church; a tangle of hockey gear on a frozen ice rink and a house almost consumed by the verdancy of its yard.

In these photos, there’s a lot of explicit engagement with the social and political texture of the neighbourhood. Richter’s pictures are full of traditional American iconography, capturing what John Szarkowski called, in Robert Frank’s work, ‘the gaudy insanities and strangely touching contradictions of American culture.’John Szarkowski, Looking at Photographs (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2009), 176. We see our symbols (the cherry tree, the flag, a bald eagle kite), as well as our rituals, both formal and improvised: a Boy Scout ceremony, a marching band, a man attacking his hedge with electric trimmers wearing a red, white, and blue sweatband around his bare head. There’s plenty of irony here, too, a reminder of those ‘touching contradictions’ – a tattered wheat-paste poster of Martin Luther King, Jr.; a building collapsed with neglect; a spatter of blood on the asphalt.

In both their formal qualities and in their blending of intimate detail and social awareness, the pictures allude to, and participate in, a recognizable tradition, one defined by Walker Evans and Robert Frank and Stephen Shore, to name a few. But Richter’s work takes this tradition of American photography and transforms it. Gone is the road trip, the effort to show the country by encompassing all of it. In its place, a local investigation, showing the country by diving deep into a small corner of it. Gone is the ironic distance of a photographer who imagines himself as apart from the world he pictures. That mythical figure was barely credible even well before the pandemic. But the pandemic and then the uprising that followed the murder of George Floyd – which occurred only a few miles from Richter’s own neighbourhood – made it impossible to preserve the old fantasy of an objective photographer floating alongside the social world, documenting it without participating in it. In its place, a photographer who is intimately engaged – for his own sake and for the sake of his son – with the world he lives in.

Richter’s pictures don’t show the protests that raged during the summer when any of these pictures were made, but they are the work of someone aware that he’s working in a world in which his status – as a white man, as a father, as a photographer – has consequences. They show him reckoning with the complexities of parenthood, helping to steer a child through a physical and cultural landscape not only of the blocks surrounding his home but also of the country he will grow up in. Richter’s perspective on America in these pictures is not the analytic point of view of an Evans or Frank – Look at this country, all paradox and hypocrisy and beauty – but rather a deeply felt plea: Look at this country: how am I to raise my son in this?

That son is present literally in only a handful of the pictures, but his presence suffuses the project. The pictures are consistent in their clarity, their stability. There is not a lot of motion here; none of the pictures are off-balance or uncentred. But beyond that superficial consistency they are curiously eclectic in their points of view. Some of them are visually taught, complex layers of line and colour. Some are as simple as a child’s drawing, and depict the kind of thing that Richter’s son might have found interesting: a dead rabbit on the pavement, mordantly outlined in spray paint as though it were part of a crime scene; a drip of paint around a door’s peephole; a stack of enormous Legos dusted with snow. Some of the pictures are tinged with the bittersweet sentimentality of parenting – a child in a swing, caught at the apex of its arc; a child’s delicate hand holding a cherry on its branch. When Julien is in the pictures, we see him at a distance, a small figure in a complex scene: here is he peering into the window of an abandoned store; here he is running into the shadows of an overpass.

The project is also full of reflections on masculinity, from the Boy Scouts assembled on a lawn to a lone bearded man in his driveway hurling a hatchet toward his garage door. There are suggestions of violence and tenderness, a complexity held best in a striking image of a man and a boy in a river. The man is standing, shirtless and with his jeans rolled up, in the water up to his knees. His hand is on the head of a child who is crouching in the river, water up to his neck. They both look directly at the camera, their bodies framed by trees. The gesture – the man’s hand on the head – looks gentle; the man looks anything but. The photograph could have interrupted a baptism or stopped a drowning.

Fourth of July on the Mississippi, 2019.

Julien’s presence in these pictures foregrounds the function of time, too. Photography generally is interested in the present and the past, what Evans described as ‘what any present time will look like as the past.’Quoted in Svetlana Alpers, Walker Evans: Starting from Scratch (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020), 25. Richter’s pictures have this memorializing function, but also work to activate our sense of time’s passing, our awareness that we are hurtling into the future. All pictures, of course, have the potential to do this, but these pictures, so infused by the energy of one moment in a child’s life, make the future feel acutely present. We think about Julien growing up (he won’t always need to stand on his tiptoes to look in the window; he’ll soon be ice skating with confidence), and so we think about the changes in everything else around him: the blood will fade from the asphalt; the hedge will grow back and need trimming over and over; someone will finish painting the house. The boy will grow: what will become of his world, his neighbourhood?

As American lives have been lived more and more in cars and on commutes, the idea of the neighbourhood has become more and more abstract – little more than a name, a zip code, a marker of identity or status. An ironic effect of the pandemic was to restore some materiality to the idea of the neighbourhood. It emptied us out onto the street, putting us in a kind of proximity to other people that many had stopped experiencing – the chance encounter on the sidewalk, a glimpse into the lives of others we’d catch as we ambled past their yards or lit windows. In a time when America’s civic fabric seemed to be shredding in the grips of pandemic, social upheaval, political gloom, these small encounters with strangers in the street seemed to restore some very basic level of social cohesion. They illustrated the point Rebecca Solnit makes in her history of walking: ‘Citizenship is predicated on the sense of having something in common with strangers, just as democracy is built upon trust in strangers. And public space is the space we share with strangers, the unsegregated zone.’Rebecca Solnit, Wanderlust: A History of Walking (New York: Penguin books, 2001), 218.

But even when these pictures are at their most obviously public, they feel deeply personal. They are a meditation on big themes, to be sure – America, citizenship, masculinity, the meaning of public life. But they are also a kind of father’s scrapbook of his son’s childhood, and an affirmation of the importance of the particular, of embodiment, of engagement. They are the story of a community being made by walking, by stopping to look, by being open to a child’s sense of astonishment at the world. They show a possible world, a possible country, in which Julien – and we – might find a way to live.

*All images from Andy Richter’s ongoing series Walking with Julien