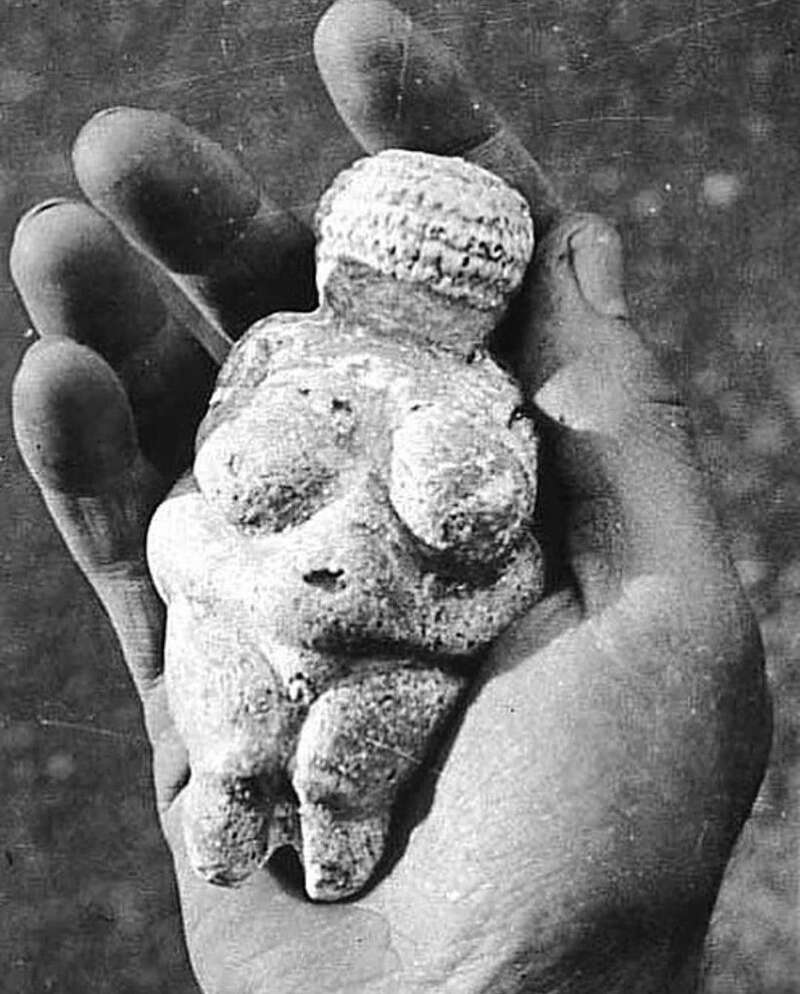

The Venus of Willendorf, possibly in the hands of her finder Johann Veran, 1908, analogue photograph, Willendorf, Austria.

Agency over Images: Who’s in Control of the Female Nude?

Lena Holzer

05 feb. 2026 • 18 min

At first glance, it was no more than an accumulation of pixels, randomly arranged. As I moved the tiny screen of the Sony Ericsson phone farther away from my eyes, the dark and light spots took the form of a prepubescent naked figure. Photographed from below, her pose disclosed everything a body could possibly have to offer at such a young age, and with her fingers she opened whatever wasn’t already exposed by the spreading of her legs.

I was around 14 years old when the nude photograph of a girl even younger than me was shared and debated over desks across the classrooms of our school. She had sent it to her former boyfriend, who, after their breakup, handled the unexpected complexity of emotions in the way many boys and men are socialised to: he passed his pain on to her by publicly shaming her.

In the hands and on the cell phones of hundreds of students, the nude came to cost her much more than the €1-something that sending a photo via MMS cost in the pre-smartphone era.

Today I don’t remember the girl’s name or face. The one thing that’s remained with me in all the years since is her pose of merciless self-display: legs open wide, camera between them, the shot brutally direct and, to me at the time, profoundly irritating – an amateur female nude produced exclusively for the eyes of a boy.

In the many years that have passed since then, I’ve sent one or two or twenty nudes to people myself, and, quite miraculously, none of them have been shared further (at least not to my knowledge). The poses in which I sometimes staged myself in those images, much like the perspective and pose the girl from my school chose for her nude, attest to how young people’s early understanding of what’s sexy and arousing is influenced by exposure to pornographic imagery. According to a 2017 study commissioned by the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children and the Children’s Commissioner, the average age at which children first see porn in the UK is 13,Elena Martellozzo, Andy Monaghan, Joanna R. Adler, Julia Davidson, Rodolfo Leyva, and Miranda A.H. Horvath, ‘. . . I wasn’t sure it was normal to watch it . . .’: A Quantitative and Qualitative Examination of the Impact of Online Pornography on the Values, Attitudes, Beliefs and Behaviours of Children and Young People, Children’s Commissioner and NSPCC, 2017. doi:10.6084/m9.figshare.3382393. and with children increasingly owning smartphones it’s likely this age hasn’t risen but rather fallen in the years since. (A few weeks ago, I was on a public bus and noticed a toddler in their pram, holding what was hopefully their parent’s smartphone and swiping through reels on TikTok. Considering an infant’s enthusiasm for female breasts as their first and main source of nurture, I wouldn’t be surprised if the algorithm provided this toddler with some premium boob content.)

That said, the study didn’t consider the pervasive way in which porn has seeped into almost every form of mass media and image production. From music to fashion to art to movies to literature, imagery and ideas that reference pornographic aesthetics are everywhere in our contemporary capitalism-driven culture, and this is hardly a new fact. In 1999, for instance, a 17-year-old Britney Spears was on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine, wearing only underwear and pressing a Teletubby toy to her chest. Snoop Dogg appeared at the 2003 MTV Video Music Awards with two adult women on leashes, and in 2002, you could go to the cinema and watch Monica Bellucci get anally raped for nine minutes straight in Irréversible by director Gaspar Noé, who, together with his comrades, is said to have introduced New French Extremity to art-house cinema.The term ‘New French Extremity’ was first coined by film programmer and critic James Quandt in his 2004 Artforum essay ‘Flesh and Blood: Sex and Violence in Recent French Cinema’, which, despite its relevance as a trigger for the scholarly debate that followed it, has been criticised for its polemic and reductive arguments. (See Tanya Horeck and Tina Kendall, introduction to The New Extremism in Cinema: From France to Europe (Edinburgh University Press Ltd, 2011), II-III.) Porn came, saw, and conquered – it came with capitalism, it saw its potential in post-feminism, and it conquered the minds of a young generation. In Sophie Gilbert’s words, it ‘has shaped more than anything else how we think about sex and, therefore, how we think about each other.’Sophie Gilbert, introduction to Girl on Girl: How Pop Culture Turned a Generation of Women Against Themselves (John Murray, 2025), xviii.

The early aughts, with reality TV’s massive rise in popularity and mainstream pop culture, presented a mass audience of millennials, myself included, with a shallow and blatantly sexist idea of womanhood that was truly profitable only for the group of powerful men who tailored it. More than two decades later, with the hyper-individualisation of Web 2.0 and social media, we’ve entered a more personal relationship with porn, and its production and dissemination are no longer controlled only by men. Today, as women, we can actively participate in economies that were built on our exploitation and commodify our own self-representation. Have we thus gained more control? Or are we merely helping the ones in control control us?

During the Covid-19 pandemic, online platforms like OnlyFans and Fansly, which allow people to create and sell sexual content, gained millions of new, mostly female users flooding them with autonomously produced pornographic material.Matilda Boseley, ‘“Everyone and their mom is on it”: OnlyFans Booms in Popularity During the Pandemic’, The Guardian, 22 December 2020. On the one hand, these platforms offered in-person sex workers the possibility of continuing to work despite strict regulations, closed hotels, and safe-distancing orders, and without having to put themselves at risk of being infected with Covid-19. On the other hand, the rising popularity of these platforms and the promise of quick money (for some, perhaps paired with the boredom of lockdown) led many women who were new to the commercial sex industry to start selling images and videos of themselves online. Suddenly, instead of being just an ominous object on the device of a hurt ex-boyfriend, the amateur female nude was a commodity that women could produce, control, and monetise in the way they wanted. A scent of agency and empowerment was in the air.

But what does it mean when women participate in the production of images that objectify them? And what potential, if any, does that have for feminism?

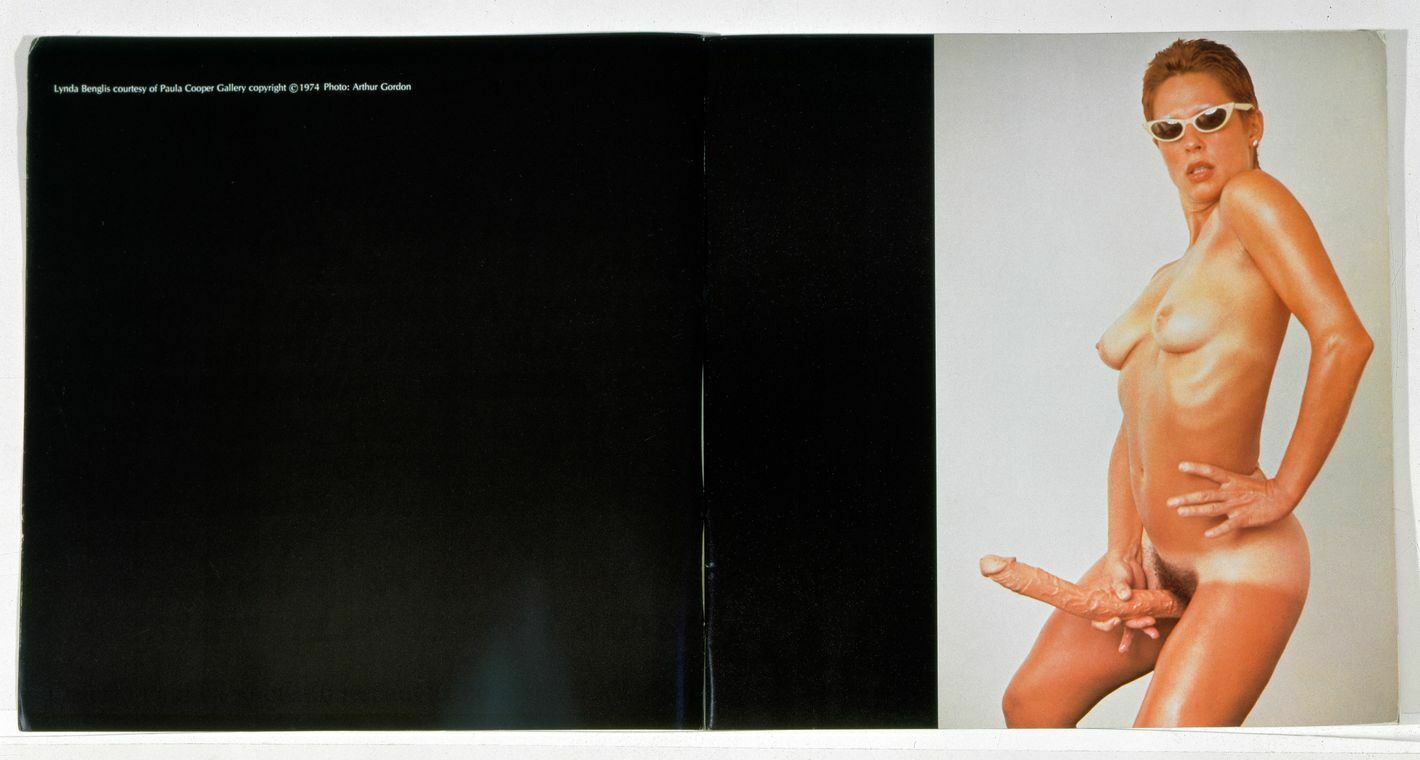

This is not a new discussion. ‘The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house’, Audre Lorde famously declared in 1979,Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Penguin Books, 2019), 105. a time marked by the feminist sex wars.The feminist sex wars were, in simplified terms, debates between anti-pornography feminists and pro-sex feminists on questions regarding the illustration of female sexuality, sex work, and pornography. Their legacy has brought with it a reductive dichotomy of ‘exploitation' versus ‘empowerment’, which denies the complexity of the lives and experiences of sex workers and women and has therefore been criticised. (See Lynn Comella, ‘Revisiting the Feminist Sex Wars’, Feminist Studies 41, no. 2 (2015): 437–462.) In the 1970s, when all means of image production and dissemination – from fine arts to cinema and television to magazines – lay almost exclusively in the hands of men, the image of female attractiveness was largely defined by patriarchal standards, which, for many women, made it incompatible with feminist intellect. The image as the most important medium of advertisement and a carrier of capitalism was looked upon with great distrust.Annekathrin Kohout, Netzfeminismus [Web Feminism] (Verlag Klaus Wagenbach, 2019), 30. Despite the work of feminist avant-garde artists like Ana Mendieta, Lynda Benglis, Carolee Schneemann, and VALIE EXPORT, to name just a few, image production as a feminist strategy was impeded for a long time, and the movement stayed first and foremost a political, theoretical one.

Lynda Benglis, Advertisement in ‘Artforum’, November 1974. Art © Lynda Benglis/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

Until rather recently, the female nude in art and popular culture continued to be produced mainly from and for a male perspective, perpetuating beauty standards that idealise white, slim, hairless bodies and exoticise any body that deviates from that. The female gaze that aims for a more diverse and truthful image, nude or dressed, is a relatively young one and is therefore still somewhat rudimentary and hard to define, as Annekathrin Kohout addresses in her book Netzfeminismus [Web Feminism]. She looks at a generation of web feminist artists from the late 2010s, among them Petra Collins, Mayan Toledano, and Arvida Byström, who became popular through social media and create work that neither shows women as victims of male desire nor co-opts male desire as a means of representation in order to occupy and criticise it. This, Kohout argues, distinguishes their perspective from that of the feminist artists of the 1960s and 1970s.Kohout, 46.

Even though the young women and girls in their photographs may not be posing for a male gaze, these images often represent the most superficial, privileged idea of what it means to be a girl – rolling around on your bed against the pastel hues of your teenage room, looking cute wearing only makeup and underwear or nothing at all, dreaming away alongside your girlfriends, who, like yourself, are carefree, skinny, and beautiful. However, this apparent agency and visibility are instrumentalised by capitalism yet again. As Emma Lewis observes,

There is no denying, for example, that . . . when [Byström] and her peers secure highly lucrative commissions (with major brands such as Gucci and Adidas) in an industry that awards four out of five jobs to men, it represents a form of progress. At the same time, the co-opting of this new imagery by corporations that are wise to social media’s fetishization of ‘authenticity’ and the marketability of feminism can be hard to reconcile with a feminist agenda.Emma Lewis, Photography: A Feminist History (Octopus Publishing Group, 2021), 223.

While these images might simply not correspond with my memory of what it was like to grow up as a girl in the Dolomites, it seems to me that the notable progress here lies in a step towards greater equality in commissioning professionals from all genders, rather than in ‘girling the gaze’.Lewis, 223.

I’d rather sell my nudes to men with an awareness of what they might use them for than visualise a superficial idea of girlhood and sell it back to my sisters as ‘normal’ under the cover of feminism.

But while, theoretically speaking, platforms like OnlyFans give women more agency over how we’re portrayed in our sexuality and offer a straightforward possibility of monetising our own images, post-feminist promises don’t hold.

Besides the moral issues with OnlyFans and its incapability to properly moderate content and report or at least delete imagery that shows child abuse or suggests human trafficking,Noel Titheradge and Rianna Croxford, ‘The Children Selling Explicit Videos on OnlyFans’, BBC News, 27 May 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-57255983.the business isn’t all that lucrative for most of its content creators. While the top 0.1 percent of creators (many of whom already held celebrity status before creating an account) capture 76 percent of the total revenue,‘Here Are the 2025 OnlyFans Statistics: Economic Insights Uncovered’, OnlyGuider, last modified 14 May 2025. the average creator is said to earn only €151 to €180 a month.Valesca Wilms, ‘Here’s All You Need to Know about Earning with OnlyFans’, Accountable, last modified 18 September 2024, https://www.accountable.eu/en-be/blog/earning-with-onlyfans/. OnlyFans itself takes a 20 percent commission on all creators’ earnings.Charlotte Shane, ‘OnlyFans Isn’t Just Porn ;)’, The Money Issue, The New York Times Magazine, updated 21 May 2021.While stars like Cardi B and Bella Thorne don’t need to show a single tit on the platform to skyrocket their already outrageous income even higher, millions of other content-creators compete against each other and unsurmountable odds for visibility, clicks, and fans, unless they fit a very specific niche. Hence, class and social status are largely perpetuated on the platform, with few lucky exceptions who manage to do well for themselves and also reveal a good sense for business.

It is, without a doubt, preferable for the production of such pornographic images to be in the hands of the women and FLINTA* persons they depict than to be in the hands of heterosexual men.FLINTA* is a German acronym that stands for Frauen, Lesben, intergeschlechtliche, nichtbinäre, trans, und agender Personen (in English, ‘female, lesbian, inter, non-binary, trans, and agender'). The asterisk represents all other non-binary gender identities.To a certain extent, this allows us to decide what we want to show and to whom. As always in the economy, however, the demand determines the supply. It would be naïve to think that, as a content creator on OnlyFans, you could entertain your audience in the long run by sharing only feet pics, underwear shots, or even nudes. The acquisition of new subscribers requires the promise of a steady supply of exciting content, and maintaining them requires the illusion of a personal relationship that might also include one-on-one sexting or the creation of customised content.Shane, ‘OnlyFans Isn’t Just Porn ;)’.In that sense, the role of men has shifted as well, from the audience and producers of porn to also commissioners who can make specific requests in exchange for money, which gives them a level of control once again.

Sex work is tough work, is often care work, and porn is an endlessly expanding business. New content needs to be exactly that, though in this industry ‘new’ assumes the comparative: more extreme, more explicit, and literally more fucked to keep viewers entertained and paying. A range of scarily look-alike OnlyFans stars act as the epitome of that logic: In 2024, 23-year-old Lily Phillips went viral for her stunt of sleeping with 100 men in one day. The accompanying documentary by YouTuber Josh Pieters gained millions of views and showed her in emotional distress after she reached her goal.Josh Pieters, ‘I Slept With 100 Men in One Day: Documentary’, YouTube, 7 December 2024, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mFySAh0g-MI. Nevertheless, a week later, she announced on X (formerly Twitter) that she was aiming for 1000 men next.Lillian Phillips (@LillianPhi28967), ‘going to be the first ever person to be with 1000 men all in 24 hours’, X, video announcement, 25 October 2024. In January 2025, Bonnie Blue, another OnlyFans star, claimed to have already reached that number.Bonnie Blue (@bonnie_blue_xox), ‘over 1000 men in a day! thank you to all the barely legal, barely breathing & the husbands’, Instagram, reel, 12 January 2025. The documentary about the sex stunt, 1,000 Men and Me: The Bonnie Blue Story, was out in July 2025 on Channel 4. (See a review by Olivia Petter, ‘Bonnie Blue Documentary Is Sad, Uncomfortable and Prurient Viewing’, Independent, 27 July 2025.Yet another content creator, Tiffany Wisconsin, is now allegedly planning to have sex with 5000 men consecutively.Tiffany Wisconsinn (@wisco.tiff), ‘Im making history’, Instagram, reel, 29 May 2025.

While these girls are busy getting penetrated and the rest of us are busy judging them for it, white male supremacy is constantly growing more powerful and misogyny seems to reach new levels. It feels like we’re going backwards rather than forward, with three Ps leading the way: patriarchy, politics, and porn.

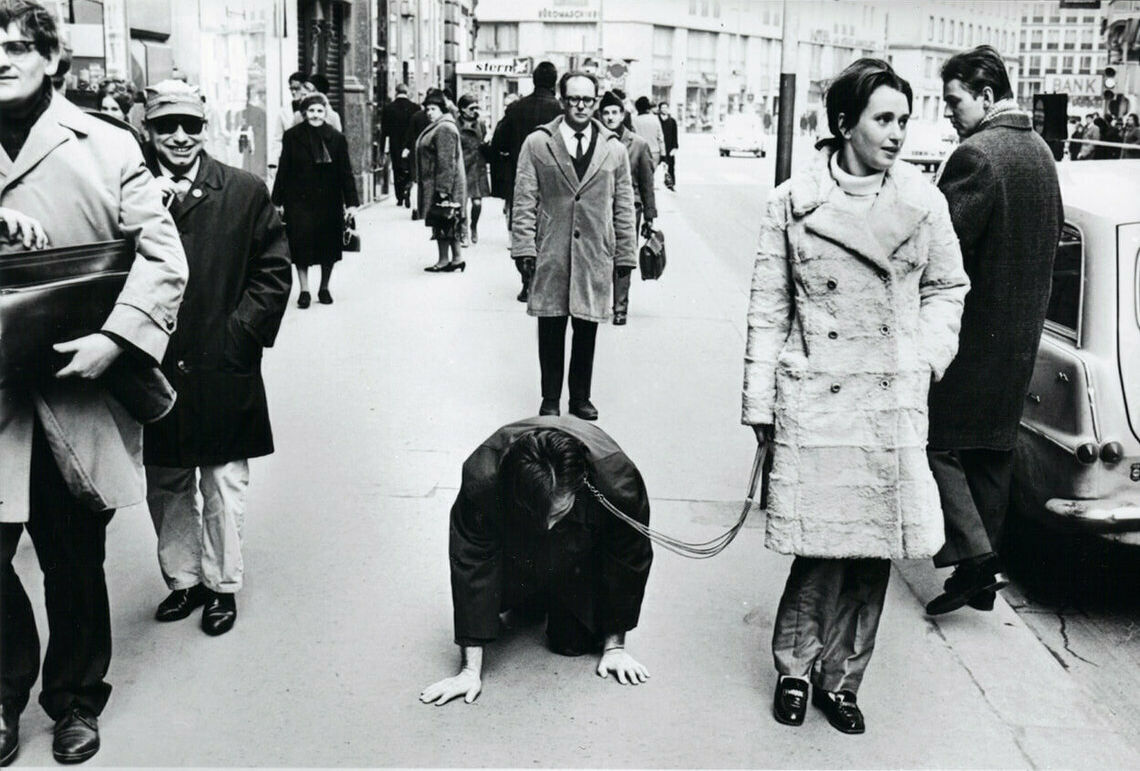

VALIE EXPORT and Peter Weibel, Aus der Mappe der Hundigkeit, 1968, Wien.

When I first started writing this essay, pop star Sabrina Carpenter had just published the cover of her latest album, Man’s Best Friend, which shows her on all fours on a pinkish carpet wearing a tight black minidress and high heels.Sabrina Carpenter (@sabrinacarpenter), ‘My new album, “Man’s Best Friend” 🐾 is out on August 29, 2025. i can’t wait for it to be yours x Pre-order now’, Instagram, post, 12 June 2025.Next to her, at the left edge of the image, we see the legs of a man wearing a suit, who is pulling on a swatch of hair at the back of her head as though it were a leash. The photograph accompanying the album’s title sparked a heated online debate, with many critics calling the image offensive and regressive. Carpenter said she was surprised by the backlash,Conor Murray, ‘Sabrina Carpenter Says She Was “Shocked” over Album Cover Controversy: “Y’all Need to Get Out More”’, Forbes, 29 August 2025.stating that she thinks of the image as a representation of young women’s awareness of when they’re in control and when they’re not. ‘I think some of those are choices,’ she said, and while that might be true, some of these choices can influence a lot of people when they’re made by a world-famous pop star like her. Amidst this controversy, I find myself wondering what’s worse: that the image is dehumanising or that it’s supposed to be empowering – ‘. . . a word that now makes me deeply suspicious any time I encounter it in the wild’, writes Sophie Gilbert in Girl On Girl, noting that she wrote the book ‘to understand how a generation of young women came to believe that sex was our currency, our objectification was empowering, and we were a joke.’Gilbert, xiii.

Post-feminism has gradually redefined feminism from a collective struggle to an individual one, but we’ll have to find one another again in order to fight capitalism in the war it’s waging against us. I don’t mean to sound cynical by using this wording, considering the actual wars and genocides currently happening in the world. ‘To speak of a war’, writes Silvia Federici, ‘is to highlight the state of emergency in which we currently live and to question, in an age that promotes remaking our bodies as a path to social empowerment and self-determination, the benefits that we may derive from policies and technologies that are not controlled from below.’Silvia Federici, Beyond the Periphery of the Skin: Rethinking, Remaking, and Reclaiming the Body in Contemporary Capitalism (PM Press, 2020), 47.

There is, undoubtedly, a sense of freedom in portraying and looking at oneself from a sexual perspective. It feels liberating, exciting, erotic. What distinguishes nudity from nakedness is who, then, gets to look at what we decide to show. As John Berger puts it in Ways of Seeing:

To be naked is to be oneself. To be nude is to be seen naked by others and yet not recognized for oneself. A naked body has to be seen as an object in order to become a nude.John Berger, Ways of Seeing (Penguin Group, 1972), 54.

What matters is not what the image shows but the meaning its content takes on once it’s carried out into the world, forming part of culture, forming culture itself. This, I think, is what we need to be critical of, Sabrina.

After four waves of feminism, the waters are still troubled. In times like these, when hope seems lost, I turn to the women I look up to – the writers and thinkers on my bookshelf. Rebecca Solnit reminds me to look further than the current moment:

So many things have changed in the last half century for women in so many countries that it would be hard to itemize them all; suffice it to say that the status of women has been radically altered for the better, overall, in this span of time. Feminism is a human rights movement that endeavors to change things that are not just centuries but in many cases millennia old, and that it is far from done and faces setbacks and resistance is neither shocking nor reason to stop.Rebecca Solnit, ‘Feminism Has Just Begun’, in No Straight Road Takes You There: Essays for Uneven Terrain (Granta Books, 2025), 127.

Silvia Federici encourages me to put the energy where it’s needed: ‘Selling our brains may be more dangerous and degrading than selling access to our vaginas’, she writes. And she continues:

[O]ur task as feminists is not to tell other women what forms of exploitation are acceptable, but to expand our possibilities, so that we will not be compelled to sell ourselves in any way. We do so by reclaiming the means of our reproduction – the lands, the waters, the production of goods and knowledge, and our decision-making power, our capacity to decide what kind of lives we want and what kind of human beings we want to be.Federici, 30.

A few weeks back, I received a messaging request on Instagram. I clicked on the requester’s profile and found a bloated white middle-aged guy with a worrying sunburn and a cowboy hat. He offered me €500 a week to provide him with several daily pictures of my feet. He would give me detailed instructions on how to pose and photograph them. I told him I would think about it.

With both my feet floating in a tepid foot bath, I’m contemplating what kind of human being I want to be.

Lisa Brice, Untitled, 2019, oil, synthetic tempera, ink, charcoal and pastel on linen, 206 x 103.2 cm.

---

This article forms part of Networking the Audience, a themed online publication guest-edited by Will Boase and Andrea Stultiens, developed in collaboration with MAPS (Master of Photography & Society) at KABK The Hague. The contributions emerge from an open call shared across the MAPS network, including alumni, and bring together artistic and critical perspectives on photography, publishing, and circulation. Together, the nine contributions reflect on how digital systems reshape authorship, readership, and meaning-making, foregrounding publishing itself as a creative and relational practice. Rather than addressing a fixed audience, the series explores how images and texts move through fluid, networked publics.