Afrapix Photographers’ Collective and Agency

Fashioning an ‘Image Space’ in Apartheid South Africa

Almost forty years ago, South Africans from a range of social, economic and racial backgrounds organised to challenge the repressive policies of apartheid, its violent police apparatus and the National Party, which had ruled the country since it came into power in 1948. Artists, cultural workers, members of fast-food workers’ unions, university student groups, faith-based organisations and members of the radical, oppositional press came together, despite their differences in race, culture, class and political opinions. Their goal: nothing short of regime change from within, with their collective power as leverage. Their vision: a non-racial future in which South Africans of all backgrounds played a part. This collective spirit, evident throughout the 1980s’ organised resistance to apartheid, was instrumental in the formation of Afrapix, one of the most influential photographers’ collectives in the country.

M. Neelika Jayawardane

06 nov. 2019 • 10 min

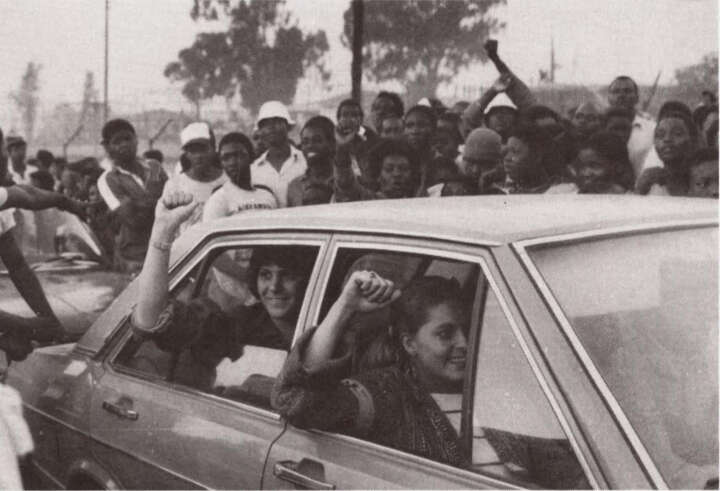

The morning after. The youth who was the target of a massacre in which twelve members of his family where shot dead. Security forces were implicated in the murders then dubbed the 'AK47 massacre'. This youth was killed several months later. KwaMakhuta. KwaZulu-Natal. 1987

©Cedric Nunn

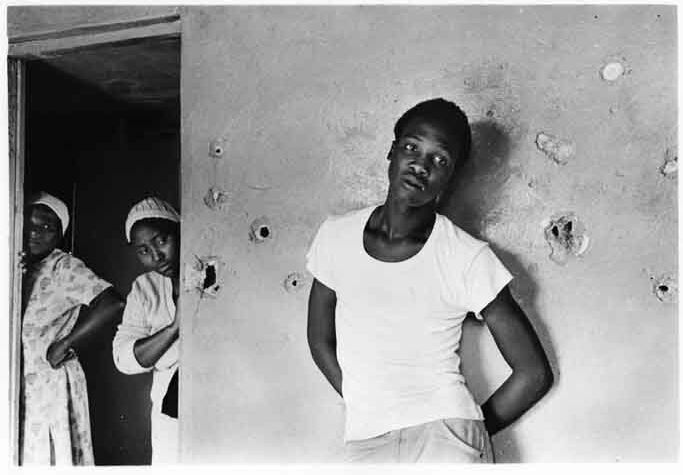

COSATU Cultural Day, JHB. 18/7/87

©Anna Zieminski, SAHA collection AL2547

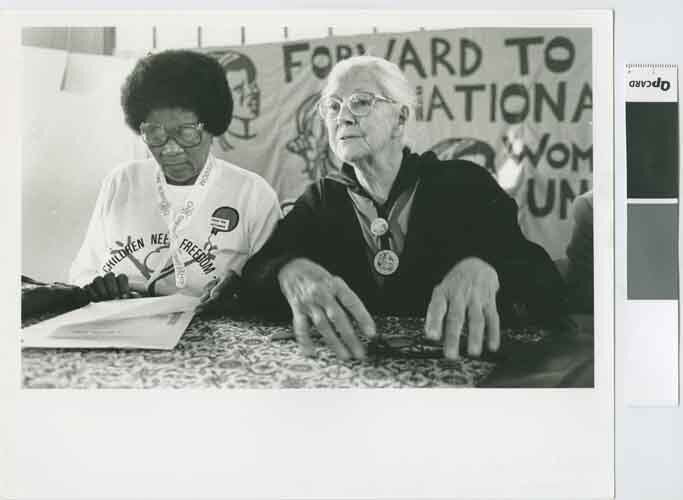

Albertina Sisulu and Helen Joseph at a FEDTRAW meeting

©Anna Zieminski, SAHA collection AL2547

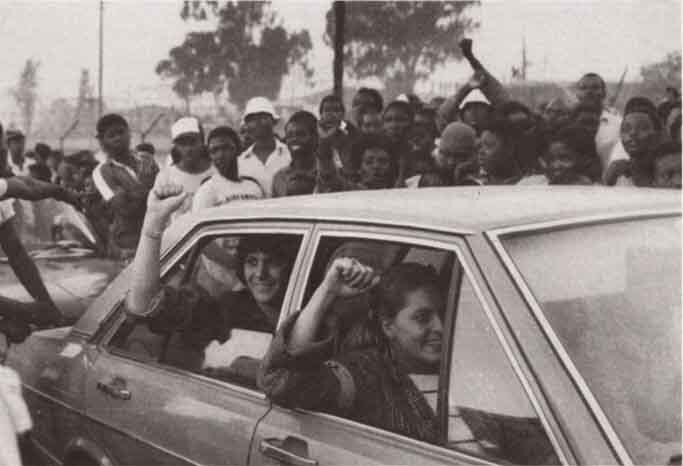

White members of JODAC visiting Alexandra to commemorate the "Alexandra massacre"

©Anna Zieminski, The Unbreakable Thread publication, SAHA collection

Woman dumped at Beestekaai North West after removal, 13 August, 1983

© Gille de Vlieg

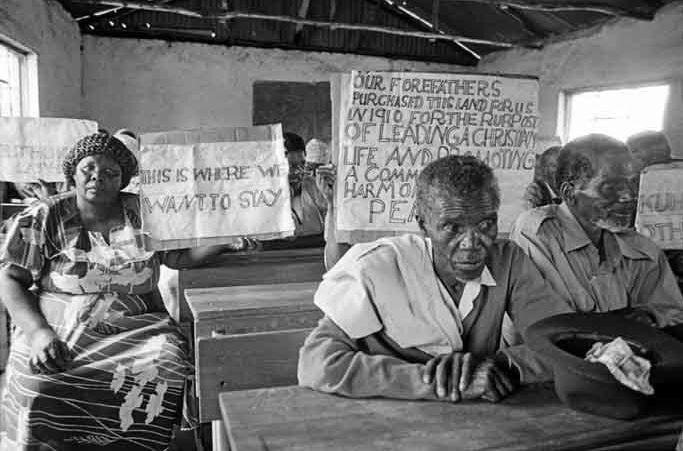

Villager's protest against removal, Cornfields KZN, 22 November, 1988

© Gille de Vlieg

Mrs Mazibuko with dead son Flints bloody T-shirt, Tembisha, Ekurhuleni, 22 June, 1985

© Gille de Vlieg

According to Afrapix cofounder Paul Weinberg, those who initially came together to discuss the possibility of forming a photographers’ collective had two major objectives: first, to become ‘an agency and a picture library’—modelled on the principles of Magnum Photos, the photographer-owned and operated cooperative founded in 1947 by the photographers Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa, David Seymour, George Rodger, and William Vandivert—and second, to ‘stimulate social documentary photography in the country.’ Weinberg, Paul. 1990. ‘Beyond the Barricades.’ Full Frame: South African Documentary Photography. 1:1: 5.Coming together during this last, turbulent decade of apartheid, Afrapix photographers wanted to ensure that photography became ‘a more effective vehicle for social change.’ Weinberg, Paul. 1984. ‘Afrapix – Going beyond the image.’ Creative Camera. July/August: 1479. They dedicated themselves to exposing the lies behind the regime’s propaganda, using photography as their medium. They provided a visual dimension to the South African resistance movement through their artistic and social documentary photography projects, as well as their journalistic work. As photographers who embraced the philosophy and principles of social documentary photography, they were motivated by the imperative to make things visible and transparent—and to bear witnesses. But many Afrapix photographers took a more radical approach. At the influential Culture and Resistance Symposium and Festival, held in Botswana in June 1982,The Culture and Resistance Symposium and Festival was organised by Staffrider and the Medu Art Ensemble (a cultural association operating in Botswana, formed by Botswanan and South African artists and writers who opposed South Africa’s apartheid policy of racial segregation and violent injustice). It was hosted by the Botswana National Museum and held in Gaborone, Botswana. It brought together a large cohort of activists, political party members living in exile and those who identified as ‘cultural workers’—artists, photographers, writers, musicians and performers. Included in the festival’s programme was an exhibition of photography. Peter McKenzie—who was, at the time, the first ‘Coloured’ person to attend the exclusively Whites-only Technikon Natal to study photography—famously stated, in no uncertain terms, that the ‘committed photographer’ must not only ‘take sides’ and ‘accept their responsibility to participate in the struggle’ but also use their cameras as ‘weapons’ in the liberation struggle.Katz, Leslie. 1971. ‘An Interview with Walker Evans’. American SuburbsX. https://www.americansuburbx.com/2011/10/interview-an-interview-with-walker-evans-pt-1-1971.html.He urged photographers to ‘be involved in the strikes, riots, boycotts, festivities, church activities and occurrences that affect our day to day living [and to] identify with [their] subjects in order for … viewers to identify with them.’McKenzie, Peter. 1982. ‘Bringing the Struggle into Focus’. Staffrider5, no. 2: 18.

McKenzie and others of his generation were inspired by the German worker photography of the 1920s—factory workers and union members who used newly available, more affordable cameras, such as Leicas and Ermanoxes.See: Ollman, Leah. 1991. Camera as Weapon: Worker Photography Between the Wars. San Diego, CA: Museum of Photographic Arts: ‘Photography entered a new age of creation in the mid-1920s with the advent of small, hand-held cameras, such as the Leica and Ermanox, capable of functioning with available light rather than flash. These cameras facilitated a new, more candid documentation of the world, while faster, more efficient rotary printing methods made this vision widely available to the German public through a proliferation of new, photographically illustrated magazines. Likewise, the Afrapix photographers’ mandate was to be participants in action, aligned with the politics and principles of the anti-apartheid movement. Their work was grounded in the belief that exposure and visibility were not the end goal; rather, the objective was ‘preconditions for an empathetic and humanistic reaction that would prompt international political action.’Campbell, David. 2009. ‘“Black Skin and Blood”: Documentary Photography and Santu Mofokeng's Critique of the Visualization of Apartheid South Africa.’ History & Theory 48 no. 4: 53. In many ways, the Afrapix photographers’ ultimate goal was nothing short of the desire to use photography as a political tool in the liberation struggle. As Pierre-Laurent Sanner’s rousing rhetoric sums up, Afrapix’s objectives were to expose the atrocities of a regime that had been in power since 1948 and, just as importantly, to foster and train a new generation of black photographers. At the time, South Africa had been experiencing the most turbulent racial history. As particularly intimate witnesses of the events of the period, photographers felt the imperative necessity of testifying to their involvement through their images.Sanner, Pierre Laurant. 1999. ‘Comrades and Cameras’. Anthology of African and Indian Ocean Photography. Edited by Saint Léon, Pascal Martin, Fall, N’Goné, and Chapuis, Frédérique. 253 – 259. Paris: Revue Noire. 253. Given the state’s repression, censorship laws and sanitised propagandistic images whitewashing the violence under which the collective lived and operated, calls for ‘objectivity’ seemed high-minded and unrealistic, if not directly feeding into the directives of the state; the times ‘did not call for objectivity, art, or multiple perspectives’ but a commitment to portray ‘the truth’.Wylie, Diana. 2012. ‘Introduction to special issue: Documentary photography in South Africa.’ Kronos 38, no. 1: 17. Afrapix needed to create a radical, oppositional image-bank to counter the surfeit of propagandistic images showing Black people as incapable of political leadership or intellectual achievement.

*

Long before the formation of Afrapix in the 1980s, South African photographers had been using their cameras—the instruments through which Black and African people were (and continued to be) depicted in denigrating ways—to write over the colonial archive and the apartheid state’s growing reservoir of propaganda. In the hands of Black South Africans, cameras and pictures became conduits for Black people to refashion themselves, re-visualising the country and its inhabitants’ day-to-day experiences in spite of the superfluity of a racist gaze. It wasn’t only a way of wresting control of the image field from the state but a visual practice essential to the struggle for political liberation and the desire for self-liberation. Black photographers also understood photography’s power to bear witness and disseminate a political message to audiences around the world.

Despite photography’s rich presence in South Africa, little to no opportunities were available for Black people interested in the discipline, this because of the racialised education system, with its built-in inequalities preventing Black learners from advancing. Black, Coloured, and Indian people were barred from attending photography classes at technikons, to which only White students were admitted. For most, imagining the camera as a conduit to engage, contemplate or theorise their outer and inner worlds wasn’t a realistic possibility.

A number of catalysts and conditions were essential to the formation of Afrapix, helping the cofounders forge a clear vision for their future. On practical and logistical levels, Afrapix’s formation was aided by the cultural magazine Staffrider.Staffrider Magazine began its first print run in 1976; it reflected the political and cultural needs of the progressive, leftist and radical youth that emerged after the 1976 student protests against the forced introduction of Afrikaans in schools. Since its inception in 1976, the magazine created a much-needed social location for ‘up to then unheard’ and unknown poets, writers, artists and photographers, so that they could learn about each other’s work.Weinberg, Paul. 1989. ‘Apartheid – a vigilant witness, A reflection on photography’. In Culture in Another South Africa, edited by Willem Campschreur and Joost Divendal. 63. London: Zed Press. Biddy Partridge, a Zimbabwe-born musician and photographer who’d worked with Staffridersince its early days, was instrumental in selecting the photographers’ work for publication. Through seeing each other’s work in Staffrider, photographers learned that there were a significant number of photography enthusiasts interested in using the discipline to document the injustices they, too, were seeing.

The idea of creating a photographers’ collective was also influenced by a prevalent cultural ethos among activists, student groups, unionists, artists and cultural workers who used collective action to push for change. At the time, photographers were generally disconnected from each other by geography, class and race. They had little to no structure to aid their development, nor did they have connections to platforms that would publish or exhibit their work. The structure of a collective provided a spatial construct, bringing together photographers from Johannesburg, Cape Town and Durban, each isolated in South Africa’s socio-political geographies of White suburban enclaves, Black townships and designated areas for ‘Coloureds’ and ‘Indians’.

Although Afrapix’s official formation as a photographers’ agency took place in 1982, they’d already begun discussions in 1981 at Staffrider publisher Ravan Press’s offices in Johannesburg. Omar Badsha, Judas Ngwenya, Jimmy Matthews, Biddy Partridge, Mxolise Moyo, Lesley Lawson and Paul Weinberg were among those at the first meeting, along with Lloyd Spencer and others from Ravan Press, including Mike Kirkwood of Staffrider.Weinberg, Paul. Interview with author. Cape Town. 26 October 2018.

Afrapix photographer Cedric Nunn, one of the collective’s first coordinators and administrators, also remembers that Rev. Bernard Spong, who headed the Interchurch Media Project, which was part of the South African Council of Churches (SACC), supported Afrapix during its early years.Nunn, Cedric. Interview with author via WhatsApp. 20 March 2019 For a small fee, the SACC provided Afrapix with an office, a darkroom connected to the office area and bookkeeping services at Khotso House, a modernist, concrete high-rise building located at 42 De Villiers Street, in the heart of Johannesburg’s Central Business District. The building became a hub, playing the important ‘role of incubating organisations that were directly confronting the apartheid state’, according to Nunn.Nunn, Cedric. Interview with author via WhatsApp. 21 March 2019 It housed alternative media groups and several community organisations, charities and NGOs, including the Black Sash and the United Democratic Front (UDF). Afrapix photographers not only created practical collaborations with these groups; in the face of police raids, restrictions and states of emergency, they provided each other with genuine support and solidarity.

*

At its height, Afrapix’s full members included a large repertoire of photographers, as well as a number of photographers who contributed their work to the agency as non-members.Full members included, in alphabetical order, Joseph Alfers, Peter Auf de Hyder, Omar Badsha, Steve Hilton Barber, Graham Goddard, Dave Hartman, Lesley Lawson, Chris Ledochowski, John Liebenberg, Herbert Mabuza, Humphrey Phakade ‘Pax’ Magwaza, Kentridge Matabatha, Rafique Mayet, Mxolise Mayo, Vuyi Lesley Mbalo, Peter McKenzie, Roger Meintjies, Eric Miller, Santu Mofokeng, Deseni Moodliar, Cedric Nunn, Billy Paddock, Biddy Partridge, Myron Peters, Jeeva Rajgopaul, Wendy Schwegmann, Cecil Sols, Guy Tillim, Zubeida Vallie, Gille de Vlieg, Paul Weinberg, Gisèle Wulfsohn and Anna Zieminski. Many young, White photographers, such as Eric Miller, remember that they were aware that the politics of the country made them angry, but they had limited experience of what apartheid meant for Black communities and individuals. He remembers that the police would regularly release a so-called Unrest Report, and the media would quote those reports, saying that due to ‘provocations by Black provocateurs, “police were forced to retaliate” or “forced to fire”’; but even then, he knew that ‘it simply didn’t sound logical or correct.’Miller, Eric. Interview with author via WhatsApp. 20 December 2018.

Anna Zieminski was 19 when she bought her first camera. It was ‘a tiny, baby Rollei’, and with that, she took photography classes at Ruth Prowse School of art, learning about F-stops, basic darkroom techniques to process and print black and white photographs, and, eventually, Ansel Adams’s ‘zone system’.Zieminski, Anna. Interview with the author. London. 2 February 2019 There were many factors that led to her political awakening; one event that stands out in her mind was the discovery of Leslie Lawson’s book on domestic workers, which she found at Grassroots, ‘a little bookshop in Observatory’, a left-leaning artists’ and writers’ enclave in Cape Town.Zieminski, Anna. Interview with the author. London. 2 February 2019 Another significant event she remembers was the day she decided to go to Khayelitsha, an area to which Black Capetonians were about to be forcibly removed. At the time, the apartheid municipal government was telling a completely different story; ‘they were trumpeting how they were building a new development … a place called “Our Home”.’Zieminski, Anna. Interview with the author. London. 2 February 2019 When she got to the location, she saw that some sand dunes had been cleared off to flatten the land, and that ‘some tall lamp posts, like [those] at football stadiums … toilets, and houses [were] beginning to go up.’ But it was nothing but a desolate, windswept area that ‘was such a contradiction to the name, “Our Home”.’Zieminski, Anna. Interview with the author. London. 2 February 2019 Subsequently, Zieminski moved to Johannesburg, where she met powerful Black women who were community workers, which also made her want ‘to know … what [else] was kept from me? I knew I was in the receiving or privileged end of the system. I felt … why had I all these amazing people been kept from me?’Zieminski, Anna. Interview with the author. London. 2 February 2019

For Gille de Vlieg, her political awakening came with a personal revelation in her 40s: ‘My daughter was about to leave; I was emotionally upset. I wanted to do something that was relevant for my own life.’ One night, she was so agitated she couldn’t fall to sleep. ‘It was … a long night of the soul. Up till then, I was a wife, mother and sportswoman.’ She read one of Andre Brink’s seminal novels - she remembers that it was Rumour of Rain or Dry White Season. The following morning, she knew that the ‘something’ she wanted to do would involve women’s organisations. She’d seen members of the Black Sash women’s organisation quietly holding anti-apartheid placards on street corners as she drove to the offices of her and her husband’s sail-making company. She ‘found the Black Sash in the telephone book’, phoned them and began working in their Advice Office. There, she learned that a root cause of the urban migration of Black people from rural areas to the city was due to forced removals of entire settlements and villages from arable, desirable land designated for Whites to ‘Bantustans’ – remote, inhospitable locations. Those displaced people were forced to come to Johannesburg in search of an income because they’d lost their way of life and their livelihoods generated through farming and rearing cattle and because of taxation by the apartheid state. She began to go to those rural areas to document what was happening and record organised resistance to forced removals. Because Black Sash had offices in Khotso House, where Afrapix was also based, she met Weinberg, who invited her to join Afrapix.

Of those who operated in Durban, there were Rafique (Rafs) Mayet, Cedric Nunn, Jeeva Rajgopaul, Pax Magwaza, Myron Peters and Deseni Moodliar (now Moodliar Soobben). Badsha generously opened his tiny photographic darkroom in the Good Hope Centre on Queen Street (currently named Dennis Hurley Street) in Durban to a disparate band of hopeful photographers from a range of apartheid-era racial groups (Black, Coloured, and Indian of both Tamil and Gujarati descent), social classes (some whose families had worked in the cane fields; others whose families were middle class business people), educational backgrounds and levels of photography experience. They honed their skills through the photography workshops Badsha organised. He invited veteran photographer David Goldblatt to, over the course of a weekend, ‘train [them] in the Ansel Adams “zone system” of developing and printing.’Nunn, Cedric. Interview with author via WhatsApp. 20 March 2019. Acts of generosity like this—by Goldblatt, in particular—helped professionalise Durban photographers, most of whom had no formal training because photography courses were typically only available to White students.

Rajgopaul had been a physics teacher who decided to leave the profession to become a full-time photographer. Nunn had been straining to find something more fulfilling than a lifetime of working at the Amatikulu sugar mill, 130 kilometres from Durban. He’d been ‘making occasional forays into the city of Durban’ to hear live music and socialise; there, he met McKenzie, then a third-year student at the Technikon Natal.Nunn, Cedric. Interview with author via WhatsApp. 20 March 2019. He remembers that upon seeing McKenzie’s portfolio, he ‘had an epiphany moment’.Nunn, Cedric. 2011. ‘The Bright Light of the Maelstrom: Okwui Enwezor interviews Cedric Nunn’. In Cedric Nunn: Call and Response. Fourthwall Books: Johannesburg. Mayet was similarly from a working class background; he’d been working at the Sasol chemical factory when he decided to leave after seeing a horrific accident that permanently disabled a fellow worker. He was at home, unemployed, when Badsha invited him to try his hand at photography.

Moodliar Soobben, one of two ‘non-White’ women to join Afrapix, came from a Durban Indian family that ran a successful business. She recalls that ‘[m]y dad [was] always reminding me that I wanted to become a human rights lawyer’, but her interest in photography took her to Technikon Natal to study photography. She became the second Black (or ‘Indian’) person to attend Technikon Natal for photography after McKenzie. Like McKenzie (who was two years ahead of her), she was forced to apply for and obtain a special permit, as a Black (or Indian) South African, to study photography at the Whites-only institution. She remembers clearly that she ‘was the only non-White in my class.’ Because of the hard-won education, she was the only person - among those in the Durban contingent who used Badsha’s darkroom, to have formal training in photography.

*

As young, politicised photographers, Afrapix’s earliest members had been independently ‘documenting the horrors of apartheid resettlement, squatter life, migrant labour [and] poverty’.Weinberg, ‘vigilant witness’, Another South Africa, 65.

Many saw themselves as comrades of the working class, intricately embedded in the struggle against apartheid, along with the greater collectivising forces of the time. Unions represented one of the most effective modes of collectivised effort, spearheading pushback against corporate and government policies that exploited Black workers. If photography is stereotypically thought of as a visual technology that works best with ‘action’ and drama—and, in the case of photography in South Africa during the 1980s, as something dependent on the actions accompanied by spectacular violence—attending trade union meetings would be the antithesis. Discussions, collective agreements and decisions moved at a glacial pace, although punctuated by moments of impassioned speeches. Yet, Afrapix photographers attended these meetings faithfully to learn about the concerns and daily struggles of union members. Reflecting back on his years as a photographer with Afrapix, Chris Ledochowski noted, ‘[e]ntire days were spent attending the meetings of one union or the other; we were highly committed and wanted to change the course of history with our cameras.’Sanner, ‘Comrades’,

African and Indian Ocean, 253. Their cameras followed and recorded ordinary South Africans’ concerns, rather than solely the spectacular moments of confrontation.

Much of the way apartheid operated was through legislation and institutional violence. To photograph those almost invisible machinations meant that Afrapix photographers became witnesses to the ‘slow processes’ of political movement towards justice and democratisation; these photographers became attuned to photographing less obvious and difficult-to-imagine violence. This meant living with the experience of the quiet, quotidian violence faced by displaced communities long after the spectacular violence of forced removal, replete with bulldozers razing homes. It meant following those who were forcibly displaced to the hinterlands and recording the violence they faced: little to no services, opportunities for work or arable land to farm. It meant being present before a community is displaced to record how they did, in fact, organise and present powerful, unified bodies that resisted, sometimes for decades, the might of the apartheid legal and policing institutions that wished to erase their existence. Leslie Lawson remembers that one of the unspoken rules in Afrapix was that they used wide angle lenses to include and reveal ‘as much of the context and the landscape as possible.’Masduraud, Nathalie, and Urréa, Valérie. 2014. ‘Afrique du Sud Portraits chromatiques’. Uploaded in 2013. https://vimeo.com/69172861 In a country with a government and legal system that actively prevented much of the ‘context’ of its divided communities as possible from entering the White public’s (and each other’s, too, by default) field of vision, this was a revolutionary photographic practice.

The practices of Afrapix photographers meant that much of their work had a remarkable quality that the work foreign photojournalists, parachuted into the country, did not. Rather than showing their subjects as a dehumanised and powerless lot demeaned and damaged by police brutality and reliant on violence as their sole means of expression, Afrapix photographers showed those people as they saw themselves: wrestling for power by any means possible, both peaceful and not. As photographers in a collective, their individuality took a back seat; they didn’t adopt the role of ‘saviour’ assuming the mantle of giving a ‘voice to the voiceless.’

Having positioned their work so clearly alongside radical, oppositional politics, Afrapix members and contributors had no doubt that they posed a threat to the apartheid regime. As Okwui Enwezor recognised, in the 1990s, photography ‘frightened the regime’ because no other form of testimony matched its ability ‘to expose and counteract the sanitized, propagandistic images working in the [apartheid] government’s favor.’Enwezor, Okwui. 1996. ‘A Critical Presence: Drum Magazine in Context’. In In/Sight: African Photographers 1940 To The Present, edited by Okwui Enwezor, Octavio Zaya and Olu Oguibe. 191. New York: Guggenheim Museum. Even when photographs showed ordinary scenes in which Black people were carrying on with life, creating culturally vibrant centres outside the confines of the depravation that apartheid’s mandates engineered, they threatened and ‘taunt[ed]’ the state, argues visual culture scholar Kylie Thomas.Thomas, Kylie, and Green, Louise. 2016. ‘Introduction – Stereoscopic Visions: Reading Colonial and Contemporary Photography.’ In Photography In and Out of Africa: Iterations with Difference, edited by Kylie Thomas and Louise Green. United Kingdom: Routledge. While these photographs depicting ‘alternative’ and thriving existences did not ‘directly attack the state [they] … ignored it’ and thus illustrated that ‘there is a space outside apartheid’s stranglehold.’Thomas, Kylie, and Green, Louise. 2016. ‘Introduction – Stereoscopic Visions: Reading Colonial and Contemporary Photography.’ In Photography In and Out of Africa: Iterations with Difference, edited by Kylie Thomas and Louise Green. United Kingdom: Routledge.

*

As Afrapix grew in influence and numbers during the mid- and late 1980s, its photographers faced challenges from increasingly oppressive media censorship laws, which restricted their movements and what they could photograph; they also faced pressures from market forces governing the media, and internal discord.

To begin with, apartheid security forces continually harassed Afrapix photographers. They lived in constant fear of police surveillance, infiltrators, spies and direct threats. In June 1986, the apartheid police raided offices of the UDF, SACC and Afrapix, all of which were housed in Khotso House. In August, the building was bombed for harbouring anti-apartheid groups, resulting in the injury of nineteen people.

Media restrictions in the country grew in ‘length, scope, and complexity with each successive state of emergency’, expanding on the ‘one hundred censorship statutes already in existence’.Trabold, Bryan. 2018. Rhetorics of Resistance: Opposition Journalism in Apartheid South Africa. 28. University of Pittsburgh Press: Pittsburgh. These restrictive laws were designed to combat ‘the public relations nightmare the apartheid government was experiencing overseas, namely, images of white police officers brutalising unarmed black civilians’.Trabold, Bryan. 2018. Rhetorics of Resistance: Opposition Journalism in Apartheid South Africa. 29. University of Pittsburgh Press: Pittsburgh.Trabold, Bryan. 2018. Rhetorics of Resistance: Opposition Journalism in Apartheid South Africa. 29. University of Pittsburgh Press: Pittsburgh.

There were also practical realities that gave pause to many executive editors as they looked at their bottom lines. The mainstream press in South Africa actively avoided running stories that showed opposition to the party’s official line. It mainly censored itself in order to survive, and it actively avoided running stories that could have been read as opposed to government policy.Trabold, Bryan. 2018. Rhetorics of Resistance: Opposition Journalism in Apartheid South Africa. 23. University of Pittsburgh Press: Pittsburgh. The paper’s White readership, from which the mainstream newspapers earned their revenue, complained that they were bored and annoyed by headlines about the experiences of Black South Africans.Trabold, Bryan. 2018. Rhetorics of Resistance: Opposition Journalism in Apartheid South Africa. 43. University of Pittsburgh Press: Pittsburgh. Moreover, the addressing of ‘race issues’ didn’t appeal to advertisers, who didn’t want to appear as though they supported dissent.Trabold, Bryan. 2018. Rhetorics of Resistance: Opposition Journalism in Apartheid South Africa. 43. University of Pittsburgh Press: Pittsburgh. That meant Afrapix photographers’ work, which conscientiously objected to the apartheid state, wouldn’t find space in mainstream newspapers. Rather, the resistance and alternative presses and anti-apartheid organisations provided space for Afrapix productions.

Life as a photographer, whether as a member of Afrapix or an independent, remained precarious, and securing a dependable source of income was difficult. According to Cedric Nunn, Afrapix photographers mostly found work with the ‘so-called alternative press newspapers … as “stringers”’,Nunn, Cedric. Interview with author via WhatsApp. 20 March 2019. independent photographers hired to take photographs of a particular event. But few of these outlets hired staff photographers, with only the odd person like Santu Mofokeng getting a staff position at The Nation.’Nunn, Cedric. Interview with author via WhatsApp. 20 March 2019. And the pay, whether from the mainstream or alternative newspapers, was poor—maybe ‘R15 per photo, starting out’, notes Nunn; even after accounting for inflation, and the fact that the pay improved later in the 80s, they couldn’t ‘make [a] living doing the news beat.’Nunn, Cedric. Interview with author via WhatsApp. 20 March 2019. If photographers were able to get jobs as stringers with foreign wire services or get commissioned to cover a story, the pay was better.Nunn, Cedric. Interview with author via WhatsApp. 20 March 2019. However, Nunn maintains that those jobs were hard to come by.

Moreover, the international media in particular demanded spectacular, two-dimensional visuals for the sake of sales and stock values. In order to make an income, photographers often felt the pressure to work in ways that were sometimes antithetical to the politics they’d come to espouse: that is, photographing communities in a way that provided deep context rather than caricatures of a violent, dystopian Africa. Given that the money was in those spectacularly violent images, photographers found it difficult to balance their desire to change and challenge visual tropes with the realities of making an income. For instance, a photograph of a ‘white policeman beating a black school child or protester’Mayet, Rafique. Interview with author. Johannesburg. 15 October 2018. would show the apartheid government as the instigator of violent actions, creating a public relations and diplomatic nightmare. But the iconography essential for such stark images of violence also depends on the continuation of predictable narratives and simple binaries between ‘good’ and ‘evil’. Even if photographs of police brutality made the apartheid regime look bad, the people they violated often appeared to be without agency.

Afrapix also developed ideological rifts within. Lawson remembers that that the legalism and didacticism embedded in Afrapix’s politics could be limiting. Although she understood photography as ‘a language’ that came with nuances and contradictions, the politics of Afrapix maintained ‘that the camera was a weapon of the struggle’.Masduraud and Urréa, ‘Portraits chromatiques’.At the time, photographers felt the pressure to internalise this refrain.Masduraud and Urréa, ‘Portraits chromatiques’.However, therein lay the conflict: ‘if you are saying it is a weapon of struggle’ notes Lawson, ‘you are making it one dimensional. And that did happen in Afrapix.’Masduraud and Urréa, ‘Portraits chromatiques’.

Conversely, as Afrapix’s influence and roster of contributing photographers grew, it became evident that not all of them were onboard with the non-racial politics and collective action that drove the activism and became the popular strategy of the 1980s. Some weren’t as committed to developing a political consciousness to undergird their work or as the motivation for their practice; others made successful careers producing images that reflected demands for stereotypes. They wanted to photograph the unfolding action and violence, a feature of South African photojournalism in the late 1980s and early 90s. Dozens of photojournalists were flying into the country, wanting to get in on the danger and adrenaline-fuelled ‘missions’. Others who became involved in Afrapix towards the latter part of the collective’s life were anti-authoritarian and rebellious, but they weren’t necessarily as articulate or clear about the need to work collectively against White supremacy. Many were rebelling against the restrictions that the apartheid regime placed on them as White youth, especially mandatory conscription into the South African Defence Forces. As Gille de Vlieg, one of the photographers who joined Afrapix early in its formative years, remembers: ‘We were really a conglomerate of, I suppose, somewhat rebellious people. All of us had a slightly “fuck you” nature, as one could put it.’ At the time, apartheid ‘gave us a unity; apartheid … and the fight against it … was always the great unifier.’de Vlieg, Gille. Interview with author. Johannesburg. 31 October 2018.

Black photographers remember that they simply had more difficulties because they came with far less resources than their White counterparts; these difficulties came about as a result of structural racism, rather than because of individually-directed racism. For instance, it was sometimes difficult for them to find transport to a particular assignment since they didn’t often have the luxury of owning a vehicle or having money for petrol; so a White photographer with those resources was likely to get the jobs that required mobility. Black photographers also had little access to the funds required for expensive camera equipment and photo-developing materials. When he moved to Johannesburg, Nunn realised that there were few in the Afrapix group who would actually spend time teaching technical proficiency to other, less experienced photographers. He remembers that though there were several White photographers with whom he felt a deep kinship, he was sometimes forced explain his (and other Black photographers’) disadvantages in stark terms:

We came from fucking Bantu education; the [White photographers] … when we asked for help from the guys who did know and had training … they laughed at us. These guys were very good at doing the talk … but it took Goldblatt to [eventually] set up the Market Photo training centre. We then became part of the original workshops that became the Photo Workshop.Nunn, Cedric. Interview with author via WhatsApp. 20 March 2019.

Nunn maintains that the ‘greatest difficulty [for Black photographers] … was not being networked into the publishing world [which was] almost entirely white at the time … [Because] whites were likely to have an “uncle in the business”, they knew more about publishing and what was possible, so were also more likely to get commissioned.’ Nunn, Cedric. WhatsApp message. 23 August 2019.

As several women photographers noted, there was very little recognition of gendered differences, or everyday sexist attitudes towards women or patriarchal expectations. For instance, the expectation that women would serve as office coordinators or in administrative positions, rather than aspire to develop their skills as photographers, was the norm. But as several photographers and office coordinators noted, these were such normative attitudes at the time that they never questioned or challenged them; de Vlieg maintains that the idea of taking on an administrative position may have, in fact, been in her own mind, as she had previously been doing administrative work for her husband at their shared business. But she, and other women who joined Afrapix simply refused to be limited; instead, they did as they saw fit—and necessary. As a member of the Black Sash, de Vlieg used her camera to document injustices and pushed to get the photographs published in order to educate a (White) public that was often ignorant of these events.

Nunn’s memories of rivalries and the sometimes-dismissive attitude he encountered from those who refused to understand the disparities and disadvantages arising from racial (and at times gendered) differences accentuate some of the less-than-idealistic issues with which non-racial collectives of the period dealt. His pointed critique illustrates that the idealistic thesis that Pierre-Laurant Sanner presented in 1999Sanner, ‘Comrades’, African and Indian Ocean, 253. —of ‘comrades and cameras’, or of a band of brothers (and some sisters), united as one, who went forth to fight a regime’s injustices using photography as their weapon—may not, in fact, be wholly accurate.

*

Afrapix disbanded in 1991 amid rising internal tensions, moves by some photographers to establish a more commercially minded agency and growing pressure from international photographers hired by foreign news agencies. However, its members’ photographs remain a unique record of the struggles waged by the mass democratic movement and the myriad of grassroots resistance groups that sprang up, as well as a record of ordinary life under apartheid in the 1980s.

Ultimately, Afrapix’s long-term impact as a collective and an agency was that its founding members engaged in the invaluable work of creating what I refer to as an 'image-space', despite ever more restrictive and often dangerous conditions. In his investigation into the ways in which the resistance press in South Africa operated under the states of emergency, Brian Trebold uses the term ‘writing space’ as a ‘metaphor to describe the parameters of expression’ and as a way to show how ‘editors, journalists, and attorneys working for the newspapers devised various legal, writing, and political tactics to maximise their writing space’ even as the government, using states-of-emergency legislation, worked to constrict expression.Trebold, Bryan. 2018. Rhetorics of Resistance: Opposition Journalism in Apartheid South Africa. University of Pittsburgh Press: Pittsburgh. This is similar to the ways in which Afrapix photographers pushed the boundaries of apartheid censorship in concert with resistance organisations and the anti-apartheid alternative-media community that emerged in the late 1970s and early 80s. Together, they helped create visual spaces in which they could challenge the narrow picture circulated by the state and mainstream media within the country and the often misleading narratives that reporters and photojournalists from international news agencies disseminated to a global public.

The collective influenced the opening up of photography to those who would otherwise, under apartheid, not have had the chance to record and disseminate their worlds and experiences as they saw them. Its legacy is today evident in South Africa’s thriving and multifaceted photography scene. It’s also evident in the historical importance of Afrapix photographers’ images; their work has contributed to how the public—both within and outside South Africa, as well as the generations that came of age in subsequent decades—envisions what it meant to live under an unjust, racist system of governance and what it meant to resist that government’s dehumanising edicts, the structures that upheld racial hierarchies and the police that maintained the status quo with violence. Their photographs remain essential to how we comprehend and decode apartheid.