In Paris, as in cities and towns around the world, the empty shelves in supermarkets are more than just signs of our last-minute panic buying before the coronavirus lockdown. The disruptions that have hit global markets have also laid bare the glaring hypocrisy of our supermarket of images, also known as our iconomy. With the coronavirus spreading in the Western world, we’re witnessing the shortcomings of crisis photography. Dead bodies are invisible, as are the faces of the suffering and panic-stricken. In fact, all the tropes we’ve come to expect from crisis photography are absent now that the West is on the receiving end. Our society works hard to limit the visibility of our own suffering while making a spectacle of that which happens abroad. Now that an unprecedented health crisis has reached Europe, we are confronted with the question of how to represent ourselves while we die in loneliness, humiliation and quarantine. So far, the output has been representative of our blind spots.

The coronavirus has further plunged contemporary photography in the aesthetic, intellectual, institutional and environmental crises that have been brooding for decades, and future waves of the virus could do the same. In fact, it’s now clear that we’ve failed to learn from critiques of how we represent suffering that have been voiced both within academia and beyond. The hypocrisy in our visual ideology of crisis photography has never been clearer. As Barbie Zelizer (About to Die) and Susan Moeller (Packaging Terrorism), among many others, have brilliantly shown, the codes of representing war, conflict and crisis are deeply steeped in a fear of seeing ourselves: it is, almost always, the other who undergoes the humiliations of wars, hunger, terrorism and epidemics. We’re asked to merely regard, gaze at or reflect on the iconicity of lost lives. Increased knowledge of these codes, steeped, if one likes, in colonial gazes, has done little to change them, and they’ve thus remained shockingly consistent since, at least, the 1970s: dead Westerners aren’t shown; dead Arab men make up a large proportion of our daily war diet; Africans are very often shown in groups and never as individuals; white people are most often portrayed as calm and composed, even when shown as victims of terror. These codes are coming back home to roost now that the crisis has reached territory that vainly thought itself untouchable to the kinds of sanitarily or ideologically inflicted plagues that have haunted all other parts of the world.

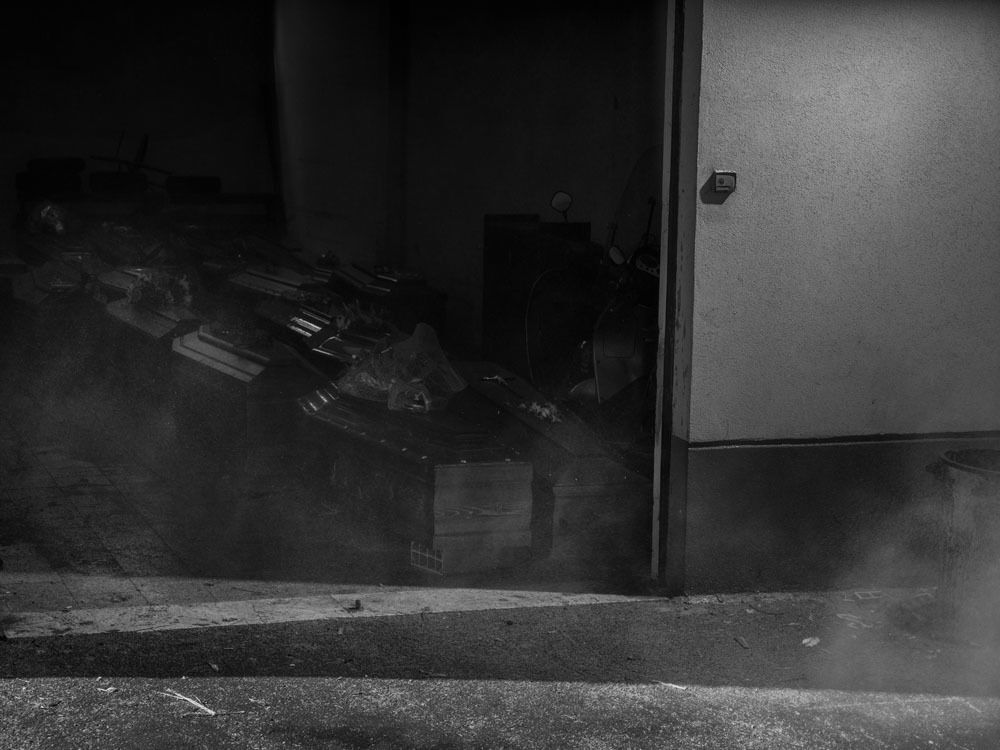

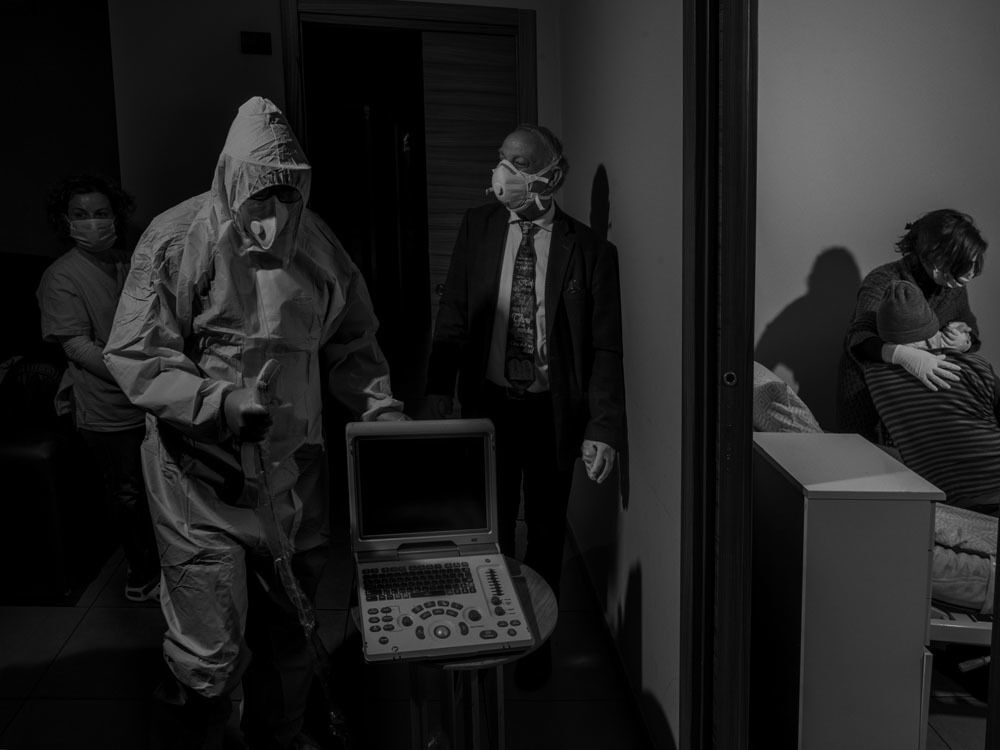

©Alex Majoli / Magnum Photos

In reading newspapers, journals and websites in my Parisian confinement, what strikes me is how fast our coronavirus codes have developed: instead of panic buyers, we see empty shelves; instead of frenzied crowds rushing to reach the safety of home, we see masked pedestrians; instead of a dying economy, we’re asked to look at deserted streets as if they’re abandoned movie sets. The war against an invisible enemy is shown not through its exceptionality but its new normality: an ordered, confined daily life, far from the chaos often portrayed when epidemics hit other regions of the world, such as Ebola in Sierra Leone, Liberia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. So far, the visualising of the coronavirus crisis seems cinematic rather than photographic. The crisis, caused by the global movement of people, seems to beg for stirring images. Heart-breaking videos of doctors and nurses in understaffed and overcrowded hospitals on the verge of collapse have marked our consciousness, not because they show the object of horror but, bowing to a cinematic trope, the reaction of the witness.

Nevertheless, we’ve seen some quality photography. The New York Times published an impressive series by Fabio Bucciarelli in which the layout, text and photography aimed to impress and shock. This was classic documentary at its finest, using innovative mise-en-page to hammer home the point that this crisis is more serious than we thought.

There are some outstanding works in progress that sidestep an all-too-common photographic response to ‘just’ document and manage to capture the current crisis in an intellectually and aesthetically challenging way. The most impressive series I’ve seen so far is by Alex Majoli and was published in Vanity Fair. It continues his aesthetic and intellectual research into the theatrical nature of photography. Shot in Sicily, it shows a stage devoid of all props and an iconomy that itself is touched by crisis. Known to foreground documentary photography’s inherent theatricality, Majoli has shot war, protest, marginal political and social gatherings and non-events.

Exhibition view of Scene, Alex Majoli, at Le Bal, Paris, February-April, 2019 (c) Alessandro Zoboli

In Scene, last year’s exposition at Le Bal, Paris, he showed his often large prints in his trademark grey-infused black-and-white. Brazil, Congo, Paris: through Majoli’s lens, all life in public spaces seems staged. In his newest series, the best work plays with our mistrust and makes us wonder if we’re looking at staged photographs (we’re not). He got close to people in intensive care, healthcare workers in hospitals and police guarding checkpoints, but most impressively, he showed numerous pictures of life on the streets, which culminated in an image of two people passing by a camera crew, adding to the surrealistic aura of his work. In fact, this image exemplifies an entire oeuvre: Majoli constantly crosses the thresholds between documentary, theatrical mise-en-scene and reflection on the production of images, all without ever fixing himself securely on one side.

Alex Majoli - Scene | LE BAL | From February 22 to April 28, 2019

Exhibition view of Le Supermarché des Images at Jeu de Paume, Paris (c) François Lauginie

The production and circulation of crisis photography is deeply steeped in the logic of the market that many photographers and artists honestly try to fight. This production and circulation are under scrutiny in an important exhibition at Jeu de Paume, Paris: Le Supermarché des Images – curated by Peter Szendy, who coined the term ‘iconomie’ in Le Supermarché du visible: Essai d’iconomie – critically unties the inextricable knot of commerce and image making. Image making is complicit in labour abuses, pollution,See the statement by Italian Vogue on publishing an issue without photographs. stocking, circulation and speculation, and it perpetuates similar conditions of production, even if it purports to criticise them. As Renzo Martens showed in Enjoy Poverty, his brilliant documentary on the perversity and complicity of photography in humanitarian crisis, the circulation of soldiers, welfare, products and images all use the same routes. From Le Supermarché des Images, it seems as if this iconomy cannot be criticised outside a self-referential loop.Marie-José Mondzain and Hans Belting already discussed the links between icons and political/financial power in their respective works. The clearest example of this link is the fact that many early portraits are those of emperors and rulers on the obverse sides of coins. Images can only be critical of image production if they engage in similar practices in a similar system. This is not unlike any all-encompassing ideology. As Martens has also shown, those who a enjoy and profit from misery are designated by institutions and imbued with the aura of honest witness, whereas locals doing the same job are considered parasites. It seems this market logic prevents documentary photography from playing the role it’s most comfortable playing: providing excruciating, close-to-the-bone visuals of conflict and crisis.

Exhibition view of Le Supermarché des Images at Jeu de Paume, Paris (c) François Lauginie

©Alex Majoli / Magnum Photos

The reason so few photographs capture the coronavirus crisis isn’t only just one of limits imposed on citizens during the lockdown – it’s equally due to our inability to imagine ourselves at the receiving end of a lengthy health crisis, the sort of catastrophe we all thought belonged to countries considered unhygienic or unstable. As mentioned, our entire society is aimed at limiting the visibility of our own suffering, whereas our visual culture is deeply engaged with suffering far from home. Another reason emerges from reading interventions on the current crisis by the usual suspects of leftist political discourse. From Judith Butler to Jean-Luc Nancy to Yuval Noah Harari, champion of easy-to-digest and all-encompassing histories, these thinkers seem to frame the current health crisis as an opportunity, an invitation to make the world anew: the post-crisis world will be rooted, they seem to agree, in today’s responses, reactions, discoveries and errors. Photography, however, by definition cannot imagine a post-crisis world. Despite calls for a photography of peace instead of war (photography, in other words, that aids in reconstruction instead of perpetuating strife by stocking an impressive but divisive and ever-available archive of images), the latter is still common currency; despite repeated calls to re-politicise photography in a world that calls for critical interventions, unpolitical documentary – a.k.a. visual storytelling practices – reigns supreme and, more often than not, safely engages with the pet peeves of middling liberalism, including humanitarian interventions in nations considered failed.

It might be too early for the photographic community to grasp this moment to honour the artistic and intellectual tradition in which it’s grounded. It’s time to finally (and in practice more than discourse) understand that crisis photography is inherently humiliating. This isn’t the issue; rather, what’s at stake is nothing less than our visual consciousness. If anything, the coronavirus crisis forces us to stare our hypocrisy straight in the eyes, to reinvent our codes and to really allow the 21st Century to begin in documentary photography.

Editor: Paul Carlucci