"There was an international conference of philosophers in Hawaii on the subject of Reality. For three days Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki said nothing. Finally the chairman turned to him and asked, ‘Dr. Suzuki, would you say this table around which we are sitting is real?’ Suzuki raised his head and said Yes. The chairman asked in what sense Suzuki thought the table was real. Suzuki said, ‘In every sense.'"Throughout this essay, I will note the original source, but some citations from John Cage are found in Kay Larson Where the Heart Beats: John Cage, Zen Buddhism, and the Inner Life of Artists (Penguin, 2012).

John Cage, A Year from Monday, 1967

"Saul once said that he was a ‘rabbinical ghost,’ meaning, I think, that he had retained vestiges of Talmudic schooling, where inquiry and the interpretation of texts were taught and fostered. He had absorbed that way of interrogating the world but had transposed it to the visual realm: he saw the streets of New York, and its inhabitants, with the narrative insight of a Talmudic scholar. The streets were his texts. His art was to recognize visual moments that evoke our deeper longings and needs, shape them through the lens of his aesthetics, and reflect them back to us."

Adam Harrison Levy, ‘The Hidden World of Saul Leiter’, in: Saul Leiter: The Centennial Retrospective, 2023

John Cage first encountered Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki in 1952, when the Japanese Zen master started teaching at Columbia University. Cage was already a major player in the New York art scene at the time; his first truly major work as a composer, Sonatas and Interludes for Prepared Piano, was composed between 1946 and 1948. Before he met Suzuki, he was also clearly seeking new spiritual paradigms to better understand human experience. Cage frequented the Asian bookstores in New York and had already found inspiration in the philosophies of Hinduism and Buddhism.

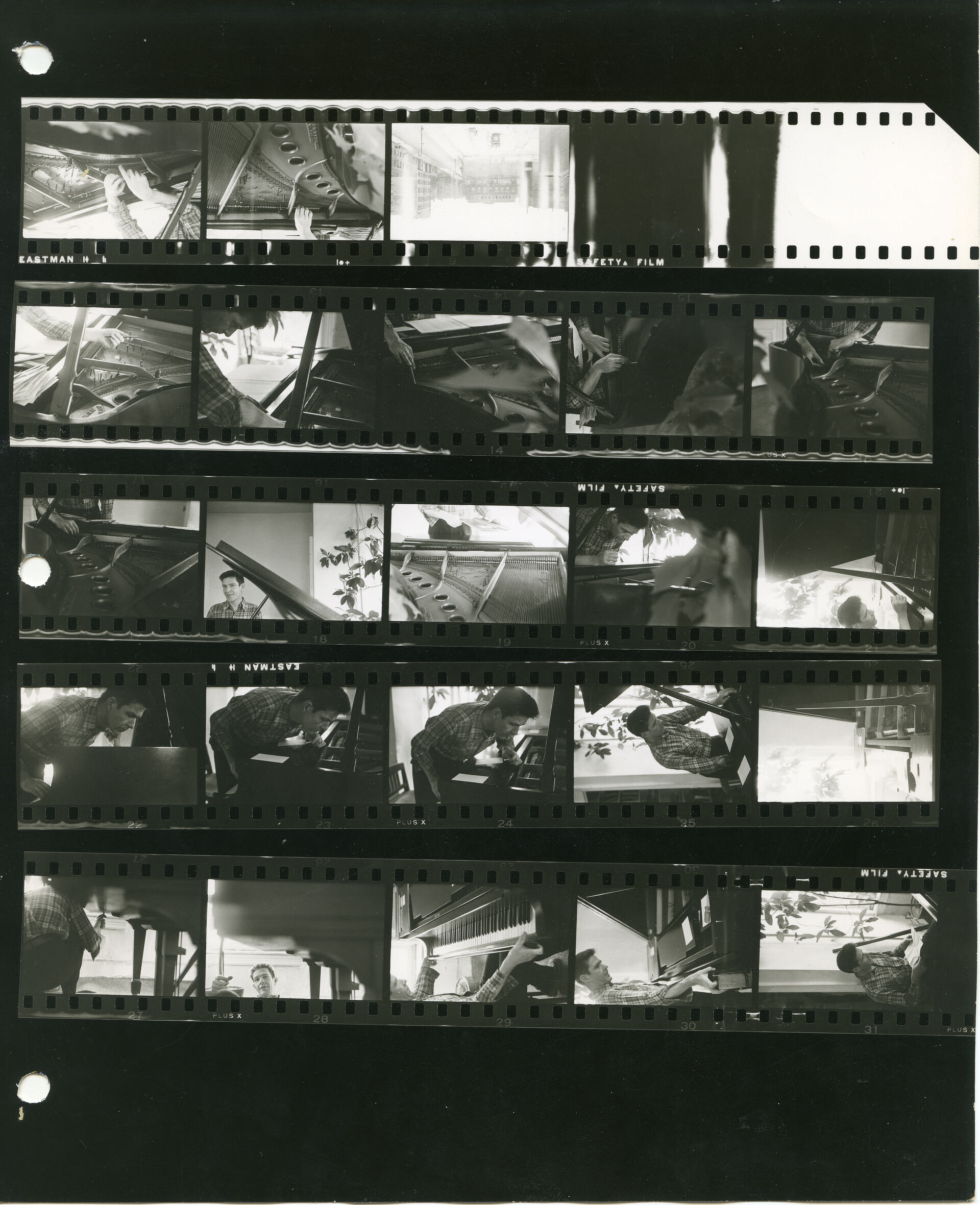

Undated contact sheet by Saul Leiter

Meeting Suzuki, however, struck Cage as an epiphany. The Japanese philosopher’s emphasis on simplicity, using an expressive but laconic approach to language, helped Cage find the best vocabulary for expressing his ideas and philosophies on art, music, and life. It was after meeting Suzuki that Cage released his philosophically challenging (and terribly simple) composition 4'33" and his profoundly influential book Silence, a collection of writing developed between 1939 and 1961. Many of the most important pieces in Silence were written after meeting Suzuki, including ‘A Lecture on Nothing’:

Excerpt from John Cage, ‘Lecture on Nothing’ in Silence (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1961), 109.

Untitled, undated. Gouache and watercolor on paper. 12 × 9 in. (30.5 × 22.9 cm).

Committed to Zen, Cage remained a central figure in the post-war cultural avant-garde in New York City, boasting friendships with Robert Rauschenberg, Yoko Ono, Buckminster Fuller, and Morton Feldman, and influenced generations of artists with his time at Black Mountain College in North Carolina.

In 1946, John Cage and Merce Cunningham were in Pittsburgh and attended a small group exhibition of local artists at Outlines Gallery. The couple bought one painting, a piece by a twenty-three-year-old Talmudic scholar in training for rabbinical life, Saul Leiter. It wasn’t long after this power couple purchased his work that Leiter renounced his studies and moved to New York City to start his life as an artist. It’s difficult to say how much the young artist’s decision was influenced by Cage’s purchasing his painting, but it is easy to believe it somehow helped tip the scales. Perhaps less obvious at the time, however, were the philosophical similarities between the two that would develop as both explored some of the deepest questions of being through art, and both strove for the simplest methodologies to express their ideas.

After moving to NYC, Leiter spent the next five or six decades living an extremely humble life, narrowly avoiding eviction from his apartment several times while sitting on the floor making Zen-like abstract colour paintings. Today he is better known as a photographer, but he did spend more of his life as a painter.Any reference to Saul Leiter’s biography are sourced from Margi Erb and Michael Parillo, eds., Saul Leiter: The Centennial Retrospective (London: Thames & Hudson, 2023). During the 1950s and ’60s, Leiter was well-known as a fashion photographer; now most know him from his photographs of New York City streets. A deep look at Leiter’s work reveals a profound commitment to simplicity, one heavily influenced by Japanese art and calligraphy. A 2023 book from Thames & Hudson, Saul Leiter: The Centennial Retrospective, provides incredible insight into the artist and his motivations, offering a clear portrait of Leiter’s philosophies and accomplishments.

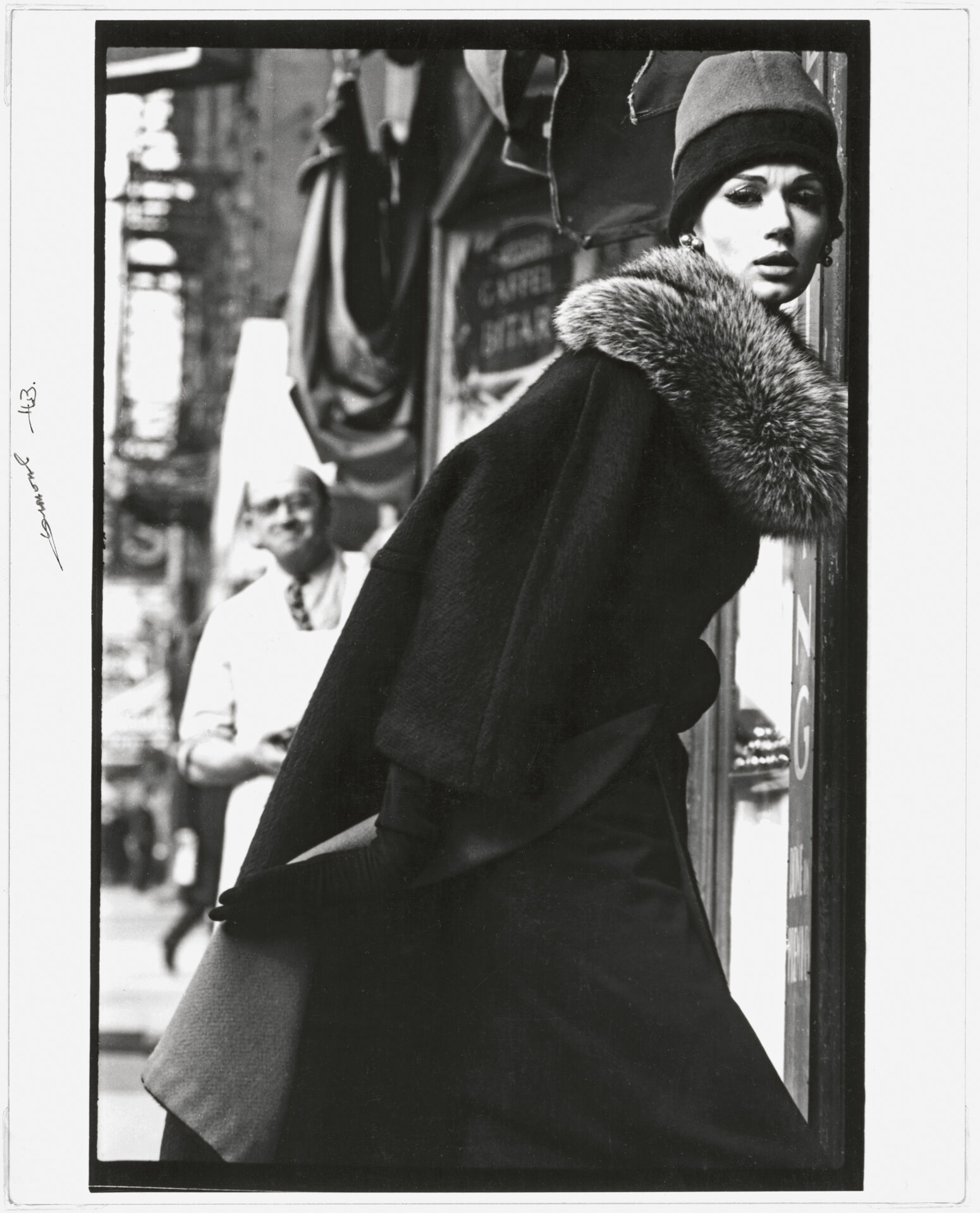

Harper’s Bazaar, July 1959 (unpublished)

*****

Leiter first found a place in history with Jane Livingstone’s 1992 publication The New York School: Photographs 1936–1963, an incredible photobook that focuses on a group of photographers coalescing around Alexey Brodovitch and Sid Grossman in the wake of the two world wars. Brodovitch was an immigrant from Russia and arrived in New York from France, schooled in both the Parisian avant-garde and the socialist design that took root during the Russian Revolution. Once in Manhattan, Brodovitch worked as an art director for Harper’s Bazaar, the legendary fashion magazine. He used his role as director to support photographers in the city by helping them secure paying gigs and important resources like film and darkroom access, and by developing his weekly tutorials on photography, design, and art. Brodovitch’s weekly seminar, called ‘Design Laboratory’, is the stuff of legend, running from 1933 through the 1950s and influencing many of the photographers featured in The New York School.Brodovitch held these at locations around New York City, even once boasting a stint at Richard Avedon’s studio. See Jane Livingston, The New York School: Photographs 1936–1963 (New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang, 1992), 279. Sid Grossman was a photographer, political activist, educator, and cofounder of the Photo League. Like Brodovitch, he had socialist leanings, and used his role and influence as an educator to promote social consciousness and politically aware photography modelled by Lewis Hine. The New York School includes fourteen photographers who were active in the city, each working in some capacity with Grossman or Brodovitch – including giants like Lisette Model, Helen Levitt, Robert Frank, Weegee, William Klein, Bruce Davidson, Richard Avedon, and Diane Arbus – and identifies them as the New York School, a distinct movement in American art that pioneered new values and visions in photography that would have global influence.

In defining the New York School, Livingston starts by looking at two other important American art movements that emerged in the post-war era, Abstract Expressionism and Film Noir. Perhaps most readily personified by Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, Abstract Expression made the physical act of painting its primary subject, believing that an unfiltered battle with the canvas could manifest the inner life of the artist. The result was paintings full of rich and visceral colours and the raw, drunken emotion of its creators. Film Noir, often characterized by heavy chiaroscuro, created dark and sinister narratives about the moral corruption that emerged in American cities after the Industrial Revolution and the world wars. Films like Double Indemnity, Pitfall, and Kiss Me Deadly explored the underbelly of bourgeoise America in the atomic age. The New York School: Photographs 1936–1963 was a defining book, the first to really identify New York as the setting for a distinct genre of street photography. In it, Livingston’s offers a succinct description of the school:

"The style seems to use the methods of documentary journalism – small camera, available light, a sense of the fleeting and the candid – and yet it rejects the anecdotal descriptiveness of most photojournalism. It is often undertaken in the spirit Sartre’s or Camus’s existentialism: a strong adherence to an idea of continual self-creation, and a quality of wanting to be responsible for one’s own identity, one’s own reality."Livingston, 259.

True to the zeitgeist of the time, the photographers channelled the Abstract Expressionists by emphasizing now and an improvisatory approach to the medium, and they found influence in Film Noir with their decidedly black-and-white vision of post-war life in America.

Untitled, undated. Gouache and watercolor on gelatin silver photograph. 8 × 10 in. (20.3 × 25.4 cm).

When first published, The New York School was greeted as an essential contribution to photographic history, but many were confused by Leiter’s being included. Sure, he was a good street photographer, but his work was gentler, and he didn’t pursue his career like Arbus or Avedon; to many, he seemed out of place in this group of photographers. In his essay ‘Close to Home, the Key to Saul Leiter’s Genius’, critic Michael Greenberg notes some of the responses to Leiter’s inclusion in The New York School:

"Leiter’s photographs are never monumental, rarely shocking. He didn’t strive for the depiction of explosive energies that was the standard of his time. Nor was he primarily interested in capturing ‘action.’ Jane Livingston chose sixteen photographers for her influential book The New York School: Photographs, 1936–1963. Leiter was the anomaly of the group. When the book was published, in 1992, his non-fashion work was virtually unknown. Vince Aletti frankly told Leiter he thought ‘at the time that [Livingston’s] claims for you were kind of inflated.’"Michael Greenberg, ‘Close to Home: The Key to Saul Leiter’s Genius’, in The Centennial Retrospective, p. 190.

No one knew anything about Saul Leiter, short of his early fashion work; he remained a fringe character, largely uninvolved with the group of photographers discussed in Livingston’s text.For a brief time, Diane Arbus lived across the street from Leiter, and on occasion the two would get together to talk shop. See Livingston, 49. Leiter was really discovered in 2006, when Steidl released their first of their three monographs of his photographs.

A lot has changed in our knowledge of Leiter since The New York School was published in 1992, and we have a much greater understanding of his accomplishments and the diversity of his oeuvre. Leiter’s street photography is exquisite but lacks the bravado of the Abstract Expressionists and the despair of Film Noir. I like to think that in 1946, when Cage purchased Leiter’s painting, he planted something much deeper. Leiter was born and raised to be a rabbi but left his traditions to pursue his life as an artist. He still embraced a spiritual life and found an entirely unique vision as an artist and photographer by embracing a quiet and simple existence, one influenced by Japanese art and calligraphy; his legacy today feels more like Suzuki than Philip Marlowe or de Kooning.Leiter did at least meet de Kooning; a photograph of the artist is included The Centennial Retrospective, p. 156.

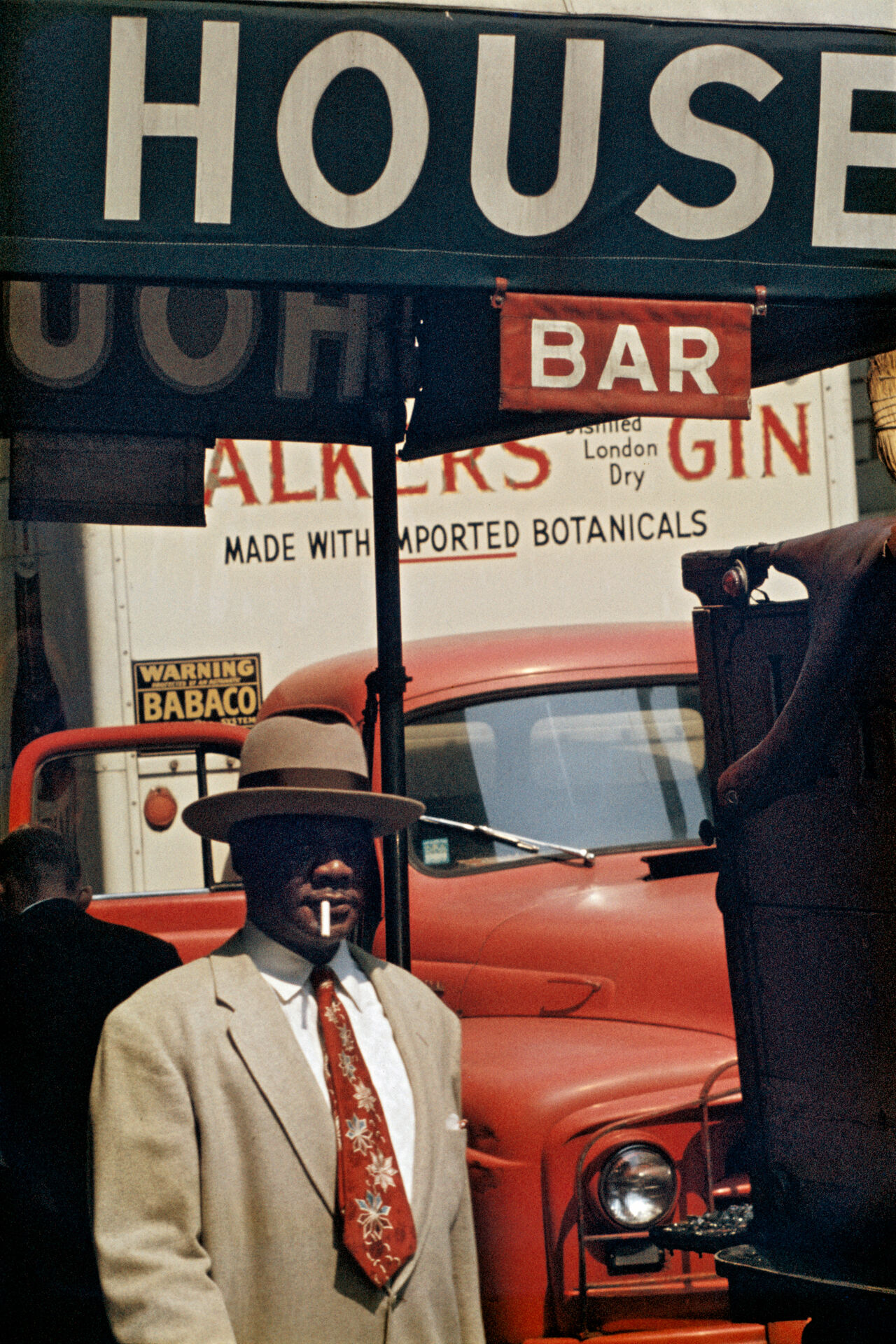

Harlem, 1960

*****

Edited by Margit Erb and the Saul Leiter Foundation, Saul Leiter: The Centennial Retrospective offers a clear and detailed biographical critique of the artist. It includes five essays by different critics and historians; the first giving a sketch of his childhood, family life, and Talmudic scholarship, and each of the others breaking down a different body of work in his archive, using biographical tidbits, interviews, and personal observation to decipher and explain his photographs and paintings, philosophies, and accomplishments. There are a few threads that emerge across the essays that are essential to understanding his work and intentions. Perhaps most significant, at least in my mind, is the incredibly small world Leiter occupied. Repeatedly, he is described as sitting on the floor of his apartment making small paintings, and when he ventured out into the streets to photograph, he never ventured more than just a few blocks from home. (His incredible photographic oeuvre was made, quite literally, just off his doorstep.)

As noted by most of the contributors, Leiter’s humility is essential to understanding his art and creative intentions. Early in The Centennial Retrospective, Adam Harrison Levy recounts a conversation he had with Leiter:

"Saul lowered himself into his chair. He looked at me intently and took a sip of coffee.

‘What drove you to become an artist?’ I asked naively.

‘I wasn’t ambitious or driven,’ he said. ‘I don’t admire success the way some people do.’ He paused. ‘I was fortunate to have fulfilled my ambition to be unsuccessful.’ And then he laughed."The Centennial Retrospective, 48.

Untitled, undated. Gouache and watercolor on paper. 10.2 × 7.1 in. (26 × 18 cm).

Levy also relates a meeting Leiter had with famed Abstract Expressionist painter Franz Kline. Apparently, Kline liked Leiter’s paintings, and told him, ‘If you only worked big, you would be one of the boys.’The Centennial Retrospective, 49. Clearly, Leiter had no interest in what Kline offered, recognizing that the humble integrity of his work was exactly what made it important and foregoing the gallery attention Kline felt validated his own. Throughout the decades he spent painting, Leiter never made anything bigger than eleven by fourteen inches. Levy recognizes the significance of this, believing that Leiter aspired to something much more substantial than a gallery career – self-identifying as a ‘rabbinical ghost’, suggesting that his work as an artist retained vestiges of his Talmudic scholarship – and that he used his cameras and brushes for a deep investigation into the nature of being.

In her contribution to the text, an essay called ‘Painting Small, Living Fully,’ Japanese painter Asa Hiramatsu addresses Leiter’s paintings and his interest in and influence by Japanese art:

"Leiter was enthusiastic in his exploration of Japanese art, and its significance regularly shows in his work. In his photographs, we see grid arrangements that are reminiscent of woodblock prints, and bold use of negative space. He understood paintings have a minimalism and an improvisational quality like those found in ink paintings. His work is alive with a Japanese aesthetic, prizing the imperfect, the impermanent, and the unfinished.

Indeed, Leiter once remarked to his friend and assistant Margit Erb that Japanese calligraphy is the pinnacle of human artistic achievement. The fluid stream of the brushstrokes must have had great appeal for a man like him who moved freely through the streets of New York as he photographed, never fixating on any one thing in the ever-changing everyday."The Centennial Retrospective, 276.

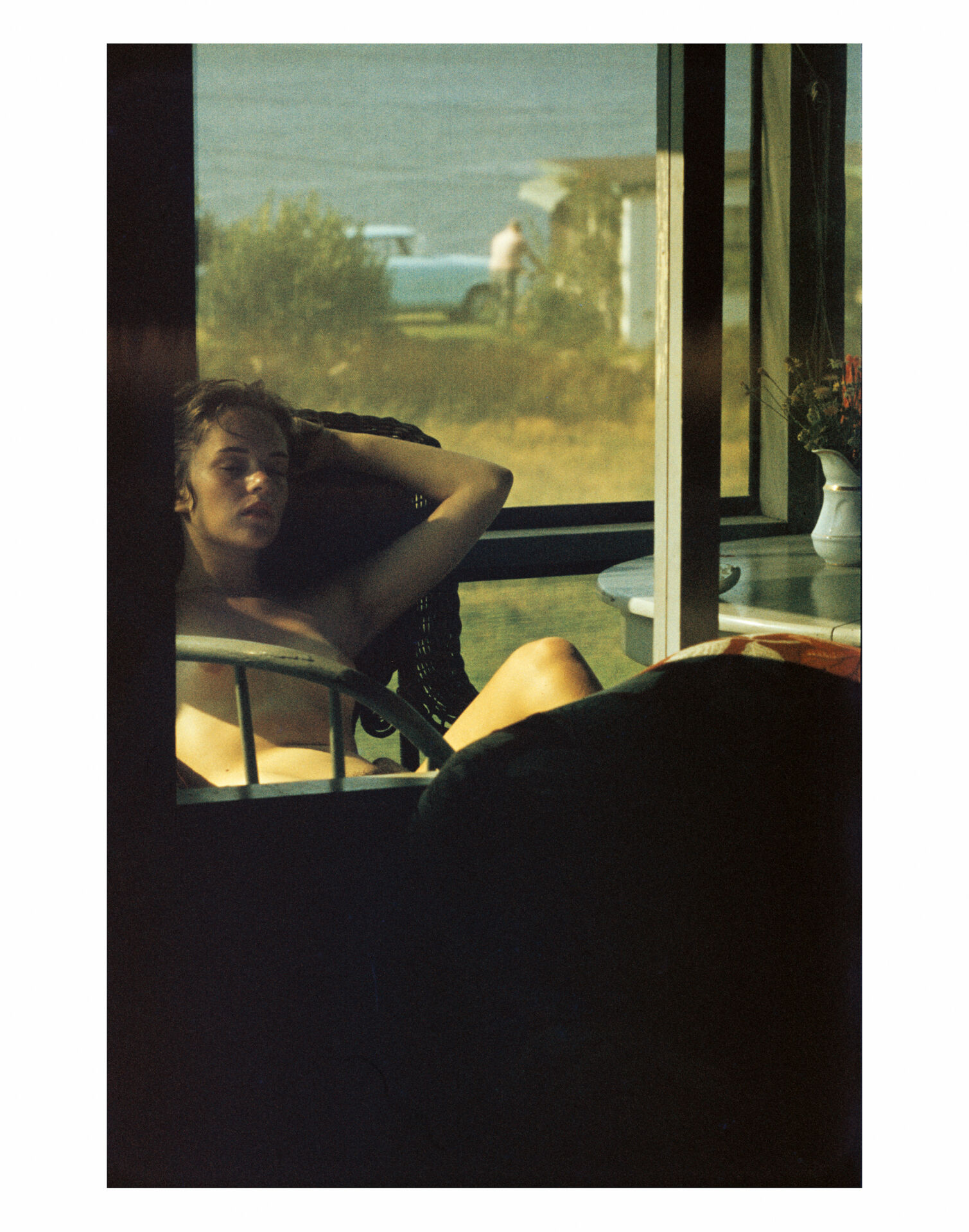

Lanesville, 1958

Clearly a kindred spirit and attuned to Leiter’s motivations as an artist, Hiramatsu identifies the Zen-like qualities in his work. I like to think of his connection to Japanese art and philosophy as a vestige of his spiritual training in Judaism, a way to reconcile his decision to leave the faith that defined his family for generations. Regardless, the undeniable manifestation of Japanese philosophy in Leiter’s photographs and paintings is a defining influence of his work, perhaps the defining influence. Leiter was an artist fully committed to a humble life, one without the need for the accolades that artists often pursue, and grounded in now, the effervescent necessity of the present, manifest in the action on the streets outside his door or in the subtlety found in washes of paint.

*****

Cage must have made a lasting impact on Leiter, because after Leiter moved to New York, he did visit Cage and Cunningham, at least a few times, and we have photographic evidence. There are several pictures of the New York power couple on the pages of Saul Leiter: The Centennial Retrospective, including an undated contact sheet in which Leiter photographed Cage preparing a piano. I wonder what the two talked about during this shoot. Did they talk about Suzuki or Silence? Did they talk about their shared interest in humility and the virtues of a quiet life?

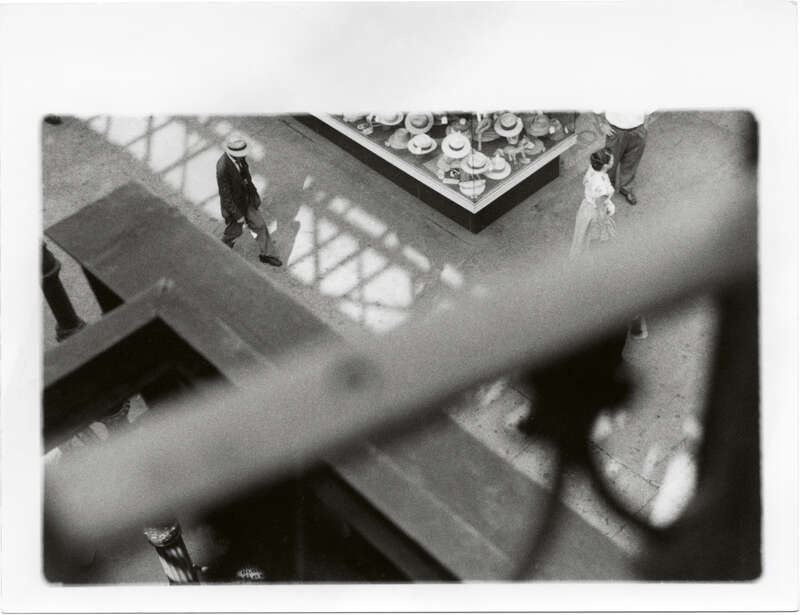

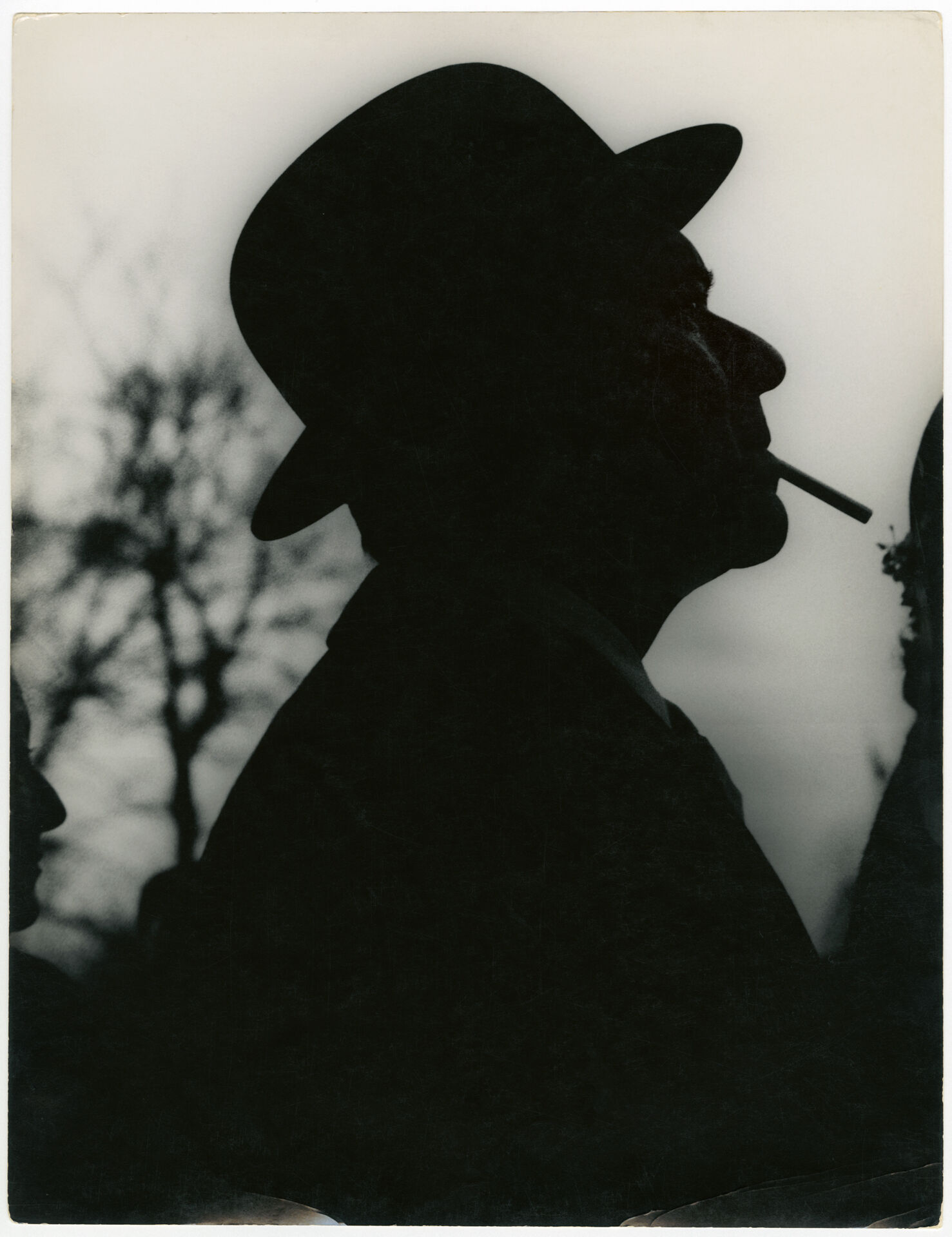

Wedding as a Funeral, 1951