Dr. Paul Julien (NL, 1901–2001)Julien’s photographic legacy and the numerous documents related to it are in the care of the Nederlands Fotomuseum in Rotterdam. was a trained chemist, a largely self-made anthropologist and an ‘explorer’ who travelled through fourteen different countries in sub-Saharan Africa between 1932 and 1962.In the film in footnote 5 and elsewhere, Julien speaks of 1926 as the starting point of his work on the African continent. This refers to his journeys to Northern Africa. The Nederlands Fotomuseum currently holds a collection of 20,000 of his photographs. A significant number of them, including 9x12 black and white negatives and autochromes, 35mm colour slides, 6x9 and 6x6 black and white negatives as well as lanternslides and vernacular prints, concern his journeys on the African continent. Julien produced his photographs in the service of science, but portraits of the people he met on his journeys were also used to illustrate interviews that were primarily concerned with Julien himself. Currently, Julien’s photographic legacy is considered to be of more importance than the outcomes of his scientific research.De Wijs, S. in Bool et al, 2007 ‘Dutch Eyes, A Critical History of Photography in the Netherlands’. 316-319; Zwolle, Waanders Uitgevers. However, he did not only ‘collect the world’ in photographsSontag, S. 1977. On Photography. 1. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. but also produced ‘statistical data’ in the form of the measurements of physical features, blood samples and fingerprints, which would supposedly contribute to the understanding of the spread and even the origin of humanity.The stories and pictures reached large audiences through lectures and four bestselling books. See this short film in which Julien himself introduces his practice: https://vimeo.com/showcase/4306567/video/195524279

Since 2012, I’ve been working with Julien’s photographs under the premise that it’s impossible to understand what we see without consulting the people whose world was depicted. I’ve taken up the responsibility of activating the collection with stakeholders from the places Julien visited, including the descendants of people who appear in the photographs, as well as artists and designers who currently contribute to the production of the visibility and imagination of future histories. The idea is that this will offer a read of the photographs beyond the context Julien gave them so we can then reconsider their value for both ‘African’ and ‘Western’ audiences.

In a series of illustrated letters, I tell Julien about my actions and share my thoughts as they develop. This format allows me to manoeuvre from speculating about Julien’s intentions and actions to reflecting on the potential value and meaning his photographs could have in the present, as well as the effects of the way I deal with my self-appointed responsibility to work with this legacy. This is the third letter in an open ended ‘correspondence’.The use of illustrated letters as a discursive format is explored in my doctoral thesis. In PJU, its potential will be further examined. In the first and second letters, I introduced myself to Julien and compared our respective methodologies and methods. All the letters will be published on www.bridginhumanities.com. Also see https://www.facebook.com/ReframingPJU and https://www.instagram.com/andreastultiens for work progressing. Two translated text fragments, which shed light on Julien’s practice, precede this letter that speaks of both recent and more distant encounters in which the impact—in terms of both effects and responsibilities—of my and Julien’s actions emerge in rather problematic and, for now, unresolved ways.

*****

Excerpt from a radio lecture by Paul Julien, broadcasted in 1933:

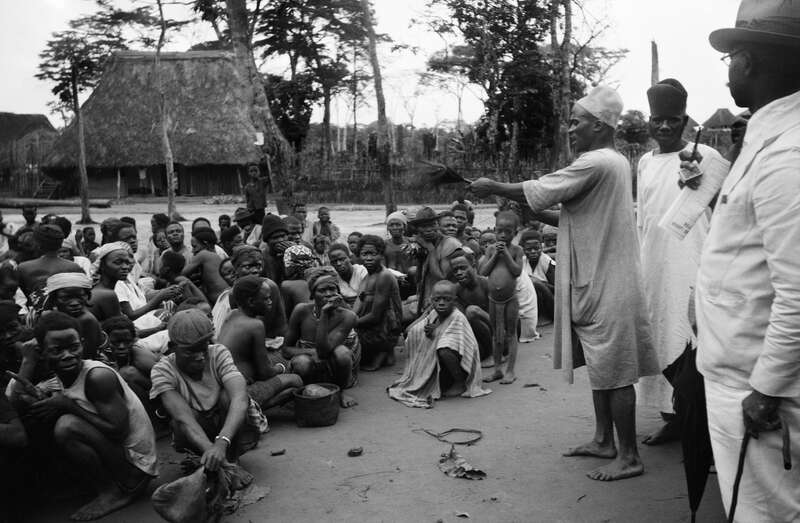

Gbarnga is an economic hub ... with a level of activity one wouldn’t expect in central Liberia. It is the seat of a District Commissioner, Mr. Ross, for whom I carried a letter from the president giving him the assignment to assist my expedition. It had been difficult along the way to get access to the materials needed for my blood research so any assistance was more than welcome. Mr. Ross went to the market with me, asked the people to squat and, helped by an interpreter, addressed them: ‘A powerful witch-man came to the village, a sorcerer, a big medicine man. Tomorrow at 8 am all those suffering from pest, all the lepers, all those with yaws should come to the courthouse to be examined and give blood.’ There was obviously a misunderstanding and the man took me to be a medical doctor. I hurried to whisper in the commissioner’s ear that I would prefer healthy people. The messenger shouted: ‘The healthy should also come, women, children all should come. The whole village should come. Understood?’ A loud applause was the result.

Early the next morning I was busy preparing for the research. Eight am there was nobody there. Nine, nobody, quarter past nine Mr. Ross grew nervous and sent out a group of messengers to force the people, with violence if need be, to the courthouse. It was all in vain. The village was completely deserted. The whole community had fled into the forest, and I may add that they did not return before I left a couple of days later.

****

Excerpt from an interview with Julien published in 1960:

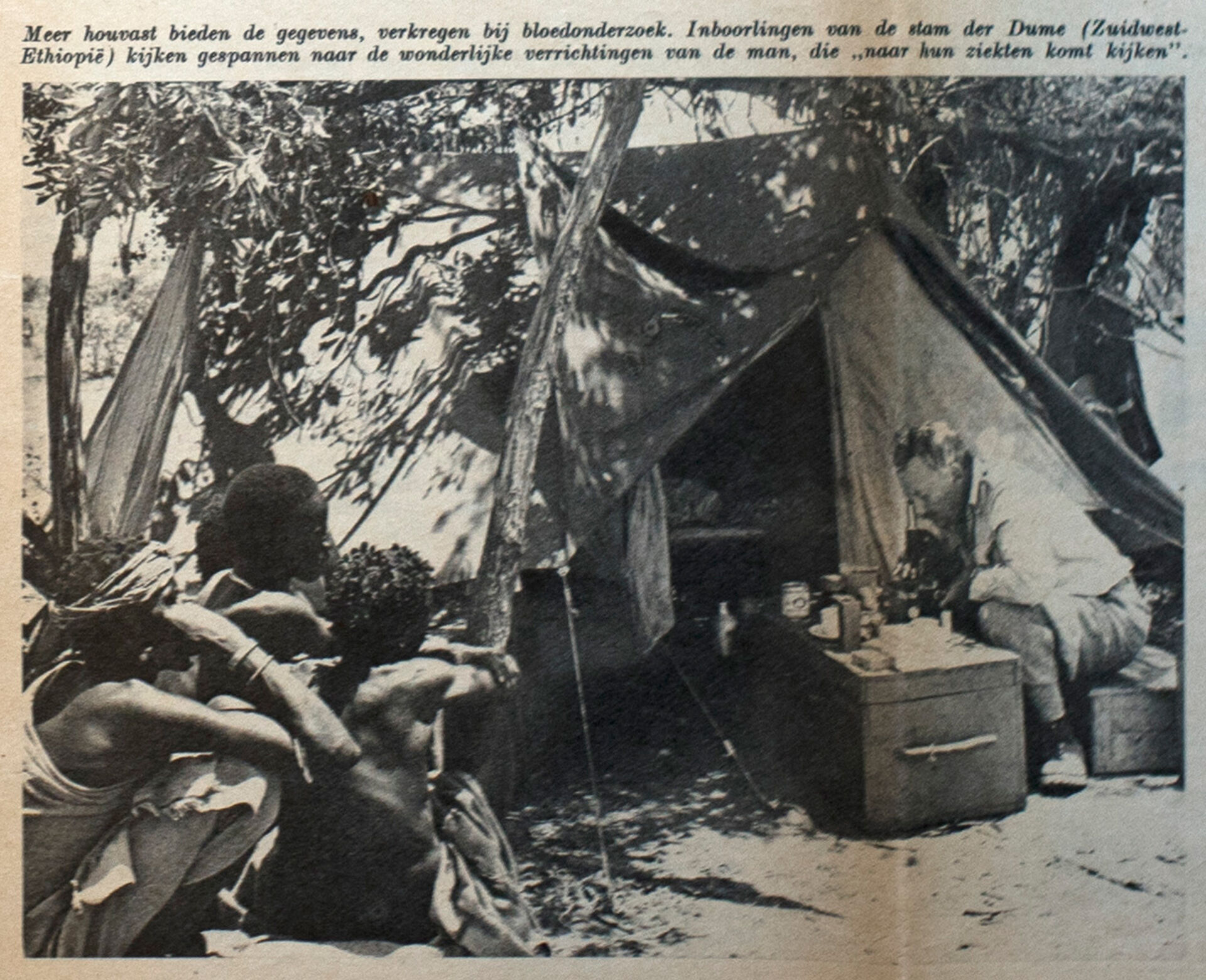

I can imagine that someone who collects blood samples is thought of as a medical doctor. There are of course photographs on which I am taking or analysing these samples while surrounded by a group of Negroes. I always tell them that I have come to see their diseases. They would not understand my true interests and also, I have been able to help many people with medication, injections and dressing of wounds. The authorities of course know better.The radio lecture was broadcasted by Dutch national broadcaster Katholieke Radio Omroep. The interview was published by the Katholieke Illustratie. Both media had a national reach and a Catholic denomination. In addition to his ideas about science, Julien also operated from a Catholic worldview.

*****

Dining hall of Itegue Taitu Hotel, August 6, 2019

Addis Ababa, Wednesday, 7 August 2019

Dear Dr. Julien,

Sixty-four years after you briefly visited this town on your way to South Western Ethiopia, I am in Addis Ababa. Yesterday, I visited Itegue Taitu Hotel, where you spent your first nights in the country. I brought a print of the Kodachrome slide you made of the accommodation. The host I met was surprised to see how much has changed since 1955. He showed me where you once stood, looking down towards the building behind the restaurant and the tennis court on its right. A banner and a truck now blocked the view. The tennis court, the host informed me, was long gone. Meanwhile, time seemed to have stood still in the restaurant itself. While enjoying my lunch, it was easy to imagine you coming down the stairs at any moment.

While I type this letter on my computer, a documentary titled The Great HackNoujaim J. and Amer, K., dirs., The Great Hack. 2019. is playing on the television set of my host, artist Michael Tsegaye. This film addresses the theft of personal data shared on the internet, a phenomenon you may remember emerging in the late 1990s. The stolen data was used to influence national elections without the ‘provider’ being aware of it. You, too, collected data from individuals you encountered on your journeys without their informed consent. This, therefore, seems to be an appropriate moment to share some thoughts with you about the relationship between our respective ambitions and the effects our actions had and could have. In other words, this letter is about impact.

PJU-colour slides box 6 [Itegue Taitu Hotel, Addis Ababa, 1955]. Collection Nederlands Fotomuseum

Last Monday, I did a presentation for a group of Ethiopian photographers and designers. After speaking about my way of working,Stultiens, Andrea. Pages 13-30 of my dissertation (https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/handle/1887/67951) I showed them the photographs and films you produced here. I added translated information from your notebook and from newspaper clippings reporting on a public lecture titled ‘Shankala’. Michael told me that Shankala, which is Amharic for ‘Black’,Shinn, D.H. and Ofcansky, T.P..,Ethiopian Historical Dictionary. 363. Washington, Scarecrow Press. is now considered to be a derogatory term because it was used to refer to people with dark skin as well as to slaves. I decided to avoid using the word. I did, however, use ‘Negroe’ and ‘Pygmy’ when quoting you, even though I’m well aware these words are considered to be offensive, too. Their past and present-day uses by non-Black people like you and me emphasise the differences between people with different positions of power. They generate a distance I consider problematic. One of the members of the audience was indeed offended by my using the words, while others argued that the messenger should not be shot.

Illustration (based on negative filed as PJU-656 exposure 3) with the quoted interview. Personal collection.

It was not the first time I encountered this kind of response to the work I, as a White European, do on the African continent or to the historical materials I bring to the table. I take this to be a reply to the privileged positions that both of us have and use to ‘take’ whatever it is we need before leaving again. This observation could result in a dismissal of ‘your’ photographs because it reduces their meaning to your position as a maker. Such a judgment, however, also dismisses the possible agency and relevance of the visibility of the people, places and objects you photographed. It eliminates the potential impact of the accessibility of the photographs forthem as it does the possibility for people in ‘the West’ to learn from them. In order for this potential to unfold, I take it as my responsibility to explain the purpose of my visit to whomever I encounter and work with. This may lead to uncomfortable situations, as was the case with the person I offended, despite my attempts to carefully position my words. It cannot, however, result in my being less honest about my intentions. Which reminds me of a question. In your writing, you repeatedly mention how the ‘natives’ you met were rude, primitive or dishonest. Did it ever occur to you that they might have rightfully thought the same of you?

Composite of exposures 5 and 6 from film PJU-657. Collection Nederlands Fotomuseum

With regards to your first major scientific expedition in 1932, I have a more particular but related concern. In July 2014, I was in Liberia for the third time. During earlier visits, I followed the same route you travelled eighty-two years earlier. I visited, as I mentioned in the previous letter, descendants of ‘King’ Kwei Dokie and prepared an exhibition of your photographs in the National Museum in Monrovia that was then about to open. Ebola, at the time a deadly and highly contagious virus, had been raging through the region for a couple of months. The crisis related to it reached a new height in the week before the planned exhibition opening. I was invited to speak about the show during the weekly governmental press conference of which Ebola was, of course, the major topic. After providing journalists with numerous facts about the virus, the minister of health addressed the people of Liberia directly through the microphones and cameras in the room: ‘You should not be afraid of the health workers, because they too get sick.’ I doubted what my ears had heard. As if aware of my incredulity, the minister repeated the remark several times. Then I remembered reading an anecdote in which the population of Gbarnga fled town because of the way in which the district commissioner had communicated the purpose of your visit. It occurred to me that the minister’s remark could’ve been part of a damage control strategy related to the actions of people like you, who through their practice generated a distance between ‘the sick’ and those coming from elsewhere to treat (and research) them. Is it possible that you contributed to the ‘fear-related behaviour’ the minister responded to?A lot has been written, particularly in mainstream news media, about this phenomenon; however, a historical perspective is rarely taken. See Shultz et al. ‘The Role of Fear-Related Behaviours in the 2013-2016 West Africa Ebola Virus Disease Outbreak’. Current Psychiatry Reports, November 2016. Would you do things differently now?

And also, going back to a more general concern about impact, would it make sense for you to be decentred from the meaning and value of the photographs you produced? This question and the others asked earlier will stay with me as I work my way towards the next letter.

With best regards,

Andrea

Governmental press conference, July 15, 2014, Monrovia, Liberia

PJU-637, exposure 1. Mission Neghelle, Ethiopia, July/August 1955. Collection Nederlands Fotomuseum

P.S. I almost forgot. Yesterday, I came across the first proof of your presence on the African continent from a perspective other than your own. Johan Helland, an emeritus anthropologist specialising in issues concerning the Horn of Africa, replied to the message I sent him. He was the eight-year-old son of the Norwegian family with whom you spent a night in Southern Ethiopia.From Paul Julien’s Ethiopia notes, private collection. He recognised all the adults in a group portrait I attached to my words. You took the picture at the mission in Neghelle. Johan does not remember you himself but recalls his mother mentioning an anthropologist who was on his way to research ‘pygmies’ and visit Lake Stephanie.

*****

The encounters generated by my engagement with Julien’s legacy continuously make me aware of certain privileges I ‘enjoy’ as a White woman, such as freedom of movement and access to resources. They also bring up the relativity of my rather specific expertise as an artist and researcher educated in the Netherlands. Little can be taken for granted when it comes to, for instance, the benefits of ‘Western’ healthcare or the ethnic categorisation of people. Spending time with Julien’s photographs where they were produced decades ago leads, time and again, to experiences that make it possible to connect particular narratives to photographs that were, so far, framed from an ideologically coloured outsider’s perspective. These experiences and narratives have the potential to expand existing ideas of ‘African’ pasts and presents for audiences both on the African continent and elsewhere. For this to be possible, they have to be presented in ways that are open-ended and inclusive of the multiple perspectives related to Julien’s legacy.