Stephen Shore, Beverly Boulevard and La Brea Avenue, Los Angeles, California, June 21, 1975, 1975.

© Stephen Shore. Courtesy 303 Gallery, New York.

A Critique of Everyday Life

The Fetishism of New Color Photography

‘Man must be everyday, or he will not be at all.’Henri Lefebvre, Critique of Everyday Life Volume I (New York: Verso, 2008), 147.

Taylor Dorrell

23 apr. 2021 • 18 min

The new color photography movement that started in the late 1960s with photographers like William Eggelston, Stephen Shore and Joel Meyerowitz saw a series of American photographers liberate photographs of mundane everyday life and move them from the vernacular to the sublime. A woman sitting on a curb, a hotel TV or used-car parking lot – everyday life was suddenly elevated beyond the everyday. Just as Freud introduced the unconscious to everyday life in The Psychopathology of Everyday Life, The Kinks did in ‘Sunny Afternoon’ and Faulkner did in his novels, the new color photographers were able to, as Mark Fisher put it in reference to ‘Sunny Afternoon’, ‘[apprehend] the anxiety-dream toil of everyday life from a perspective that floated alongside, above or beyond it.’Mark Fisher, K-Punk (London, United Kingdom: Repeater, 2018), 759. Today, the challenge is to resist the surface-level nostalgia of aesthetics in the new color movement and tap into the dormant functionMatt Colquhoun used this term to reflect Mark Fisher’s interest in the counterculture of the 1960s to 1970s that, in Fisher’s view, had potential to be pushed further than the escapism of the hippy movement, which Fisher wanted to push in his unfinished work Acid Communism: ‘It is the dormant function of psychedelia, in this sense, rather than its familiar aesthetic form, that remains relevant to us in the present moment: the way the word itself, all aesthetic associations aside, connotes the manifestation of what is deep within the mind, not simply on its surface.’ Matt Colquhon’s introduction to Mark Fisher’s Postcapitalist Desire: The Final Lectures, (London, United Kingdom: Repeater, 2021), 7. that lies beneath.

The visually pleasing and romanticised nature of American new color photography has largely remained aestheticised or simplified in critiques and writing. The art world’s aestheticisation and institutionalisation of the genre has paralysed its political and practical potential. Seen through the Marxist lens of thinkers like Henri Lefebvre, these deadlocks can be breached, and a new wave of colour photography can be sparked. Using Lefebvre’s formulation of a revolutionary perspective on everyday life, perhaps somewhere beneath the surface of new color photography also lies a dormant potential for a utopian imagination.

The new color photography movement was a drastic departure from the early-mid twentieth century black and white photography that also used everyday life as its subject. The brutally honest photography that came out of the post-WWI era, like that made through the Farm Security Administration, sparked a humanist movement of photography and journalism that reflected the harshness of poverty and the reality of life for the working class during and after the Great Depression. Ultimately, it exposed not only the brute aesthetics of poverty but also the conditions in which poverty and inequality flourished. Photographers generated a new consensus by exposing everyday life in all its squalor, insisting that economic, social and political systems required a drastic transformation.

The black and white humanist photography that flourished in that era did so in a very specific historical context (during the Great Depression and the subsequent FDR years). The photographs exposed the reality of everyday life, raising a collective awareness that these conditions were symptoms of the historico-political context. This consciousness raising remained relatively absent from the new color photography of the 1960s and 1970s. That era saw an overabundance of commodities, increased alienation, even more advertising and imagery projected through technology, intensified political resistance and a looming economic decline that pushed the political economy towards privatization, deregulation and the gutting of labour power, all of which constituted a structural framework masked by the aestheticisation of new color photography. New color photography was reduced to a depoliticized visual and nostalgic appeal.

At the time, colour photography was considered too commercial and amateurish to be anything more than vernacular photography and so new color photography was birthed out of this commercialized foundation, reflecting the commodity-centred social context it existed in. The new color movement embraced this commodity-centred society; take the cover of William Eggleston’s Guide, which features a new tricycle photographed triumphantly from below, or his famous image of a glass inside a plane, which looks like an alcohol ad. There was also Shore’s Uncommon Places, which is made up of extremely common commercial and retail landscapes, along with his images of televisions, toilets and meals. New color photographers were able to take an accelerated capitalism, with all of its overabundance and technological innovation, and harness it culturally.

It wasn’t just objects and commodities that were so central to society or new color photography; rather, having and desiring them. This was Marx’s point when he said an ‘object is only ours when we have it…. Thus all the physical and intellectual senses have been replaced by the simple alienation of all these senses; the sense of having.’Karl Marx, Early Writings (United States: McGraw-Hill, 1964), 159-160. And so, too, was the estrangement of images, which was overcome by the having of objects or images. Susan Sontag saw similarities between photographers who ‘take’ pictures and those who ‘collect’Susan Sontag, On Photography (United States: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1977). printed pictures, but one could argue that taking a picture is also the collecting of moments through pictures - the having of moments. Photographs are therefore moments transformed into objects to have, and the new color photography movement didn’t shy away from this or worry about its ethics.

Everyday life in the United States was (and still is) centred around commodities, and so the photographing of everyday life revolved around commodities and the photographing of commodities around everyday life. In On Photography, Sontag wrote, ‘[p]hotographs document sequences of consumption carried on outside the view of family, friends, neighbors.’Sontag, On Photography. Everyday life was the vessel in which these social and economic influences were illuminated. Marx emphasised this in The German Ideology when he wrote that

life involves before everything else eating and drinking, housing, clothing and various other things. The first historical act is thus the production of the means to satisfy these needs, the production of material life itself. And indeed this is an historical act, a fundamental condition of all history, which today, as thousands of years ago, must daily and hourly be fulfilled merely in order to sustain human life…..Karl Marx, The German Ideology, (1845). https://www.marxists.org/archi...

At the time of Lefebvre’s first volume (1958), he pointed out technology was evolving at unprecedented speeds to automate and smoothly run industries, but little was done to meaningfully and positively shift the everyday lives of workers. Today, the opposite appears to be happening; everyday life is filled with draining technological evolutions, but work has shifted minimally (the jobs of today are just freelance versions of the 1960s with more hours and less security – amazon workers are still assembly line workers, service jobs haven’t changed, uber is just a freelance taxi service, Walmart workers are still retail, and even obscure jobs like podcasters are just patreon supported radio hosts).Lefebvre said in his third volume of A Critique of Everyday Life that the evolution of technology, ‘[r]ather than a metamorphosis of daily life, what occurred was, on the contrary, the installation of daily life as such, determined, isolated, and then programmed. There ensued a privatization of the public and a publicizing of the private, in a constant exchange that mixes them without uniting them and separates them without discriminating between them; and this is still going on.’ Henri Lefebvre Critique of Everyday Life [the one-volume edition] (New York: Verso, 2014), 815. Nevertheless, everyday life illuminated the past just as it does the present, and it’s everyday life that’s a ‘historical act, a fundamental condition of all history.’Marx, The German Ideology, (1845). https://www.marxists.org/archi...

Stephen Shore, Holden Street, North Adams, Massachusetts, July 13, 1974, 1974.

© Stephen Shore. Courtesy 303 Gallery, New York.

Alienation

In the commodity-centred America of the 1960s and 1970s, people became alienated from notions of the self and the social collective. Central to the Marxist critique of a commodity-driven society and Lefebvre’s critique of everyday life is this notion of alienation. The Marxist theorist Erich Fromm generalised this alienation as ‘experiencing the world and oneself passively, receptively, as the subject separated from the object.’1Erich Fromm, Marx’s Concept of Man (Chippenham, United Kingdom: Continuum, 2003), 37. Alienation has largely gone unaddressed in photographic discourse, but the notion of a subject separated from its object does not just apply to labourers in processes of industrial production in which human productivity is weaponised through repetitive and meaningless tasks for the sake of generating profits – it is also central to the medium of photography and specifically to the new color photography movement. This more general Marxist definition of alienation constantly shifted in the context of new color photography; specifically, the photographer was both the subject who photographed the object and the object who photographed the subject. Here, alienation occurred via the photographing of an alienated society as well as the position of the photographer – who collects moments everyday life as opposed to being fully immersed within it – was alienated from the object/subject.

Historically, photography has been critiqued as a lifeless and mechanical process, but rarely has this conservative argument been connected to Marx’s description of the factory as a ‘lifeless mechanism’ in which work becomes a ‘labour of overlooking, thereby dividing the workers into manual labourers and overseers, into private soldiers and sargeants of an industrial army.’Karl Marx, Capital Volume I (United Kingdom: Penguin Books, 1990), 549. Photography is quite literally a ‘labour of overlooking’; photographers assume that position in relation to the subjects they photograph, and new color photography was no exception.

The Deviant

Alienation isn’t just reserved for industrial production – it also extends to those who own the means of production as well as the bourgeois subjects who are put in positions in which awareness of this alienation is harder or impossible to arrive at because it leads to the rejection of their own social primacy. Eggleston and Shore, the two main instigators of the new color photography movement, both grew up in bourgeois environments they didn’t fit in to. Eggleston was born into a well-to-do family in Mississippi, where he went against the stereotypical interests of hunting and sports. Growing up in boarding school, he instead pursued artistic endeavours. Shore, meanwhile, was born an only child to parents who owned a handbag company and was introduced to photography at a young age when his uncle gave him a darkroom kit. Both Shore and Eggleston went their own ways and joined a sort of bohemian class that became prominent in the late 1960s. Shore became a regular at Warhol’s Factory in Manhattan, and Eggleston drifted around universities without earning a degree before he was introduced to photography.

They were both, in many ways, what Lefebvre called a ‘reverse image’ of their bourgeois backgrounds. Both estranged from and immersed in their everyday lives, they became deviant – or reverse – images, and they ‘[revealed their] alienation by dishonouring it.’Lefebvre, Critique, 12. Shore and Eggleston both revealed the superficiality of the bourgeois by rejecting it, in their case, through artistic pursuits that exposed this very alienation through the reverse image of colour photography. They inverted the commercial and amateur medium of colour photography to an artform that addressed and became the reverse image of the political economy that birthed it.

The Fetishism of New Color Photography

Eggleston’s and Shore’s subjects were everyday objects and people, but there was always something that made the photographs more appealing and transcendent than personal family photos, an aesthetic edge that viewers couldn’t identify but that made everyday life appear more interesting than the actual experience of it. In her introduction to British Photography from the Thatcher Years, Susan Kismaric described this phenomenon as ‘an omnipresent tension that has crept into the very fiber of a place in which daily life is permeated by an insidious, unseen enemy.’Susan Kismaric, British Photography from the Thatcher Years (United States: The Museum of Modern Art,1991), 16. There’s nothing romantic about a small shop with boxes full of fruit stacked out front or cars stopped at a red light, but these photographs evoked a romanticised appeal beneath which there was an ‘insidious, unseen enemy.’

This sublime nature of a new color photography haunted by neoliberalism was the same process that Marx described in his notion of ‘the fetishism of the commodities and the secret thereof’. He observed that a commodity is ‘at first sight, a very trivial thing, and easily understood’ but added that ‘[i]ts analysis shows that it is, in reality, a very queer thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties.’Karl Marx, Capital Vol. 1 (United States: Random House, Inc., 1906), 81. New color did something similar but, in some ways, flipped. The image was at first rather appealing, with seemingly ‘metaphysical subtleties’, but in reality, it was trivial, just an old car or gas station. And thereafter the triviality followed Marx’s fetishism of the commodity.

For Marx, the ‘mystical character of commodities’ hid the complex relations of production in which the only social connection to workers were the physical commodities they produced. Marx used a very photo-relevant analogy to explain the phenomenon:

This is the reason why the products of labour become commodities, social things whose qualities are at the same time perceptible and imperceptible by the senses. In the same way the light from an object is perceived by us not as the subjective excitation of our optic nerve, but as the objective form of something outside the eye itself. But, in the act of seeing, there is at all events, an actual passage of light from one thing to another, from the external object to the eye.Marx, Capital, 83.

Something similar was happening in new color photography. We perceive new color photographs not as a document of the symptoms of a socio-economic system but as an aesthetic art form of individuals (photographers) – something sublime. But, in the act of creating the photographs, there was nonetheless a documentation of the socio-economic system of the time, even if it was hidden beneath mystical or sublime-looking commodities and images.

In the 1970s, the bohemian class notoriously started to withdraw from collective and political struggles in favour of an individualism that, in the 1980s, would be appropriated by the capitalist systems it tried to reject. New color photography, at first glance, reflected this escapism (Shore and Eggleston didn’t photograph anti-war protests, for example). However, they worked within the landscape of everyday life – rejecting surrealism and working outside the political events of the 1960s and 1970s. From that position, they unintentionally presented a critique of the very systems that so many of the era’s politically charged movements attempted to change.

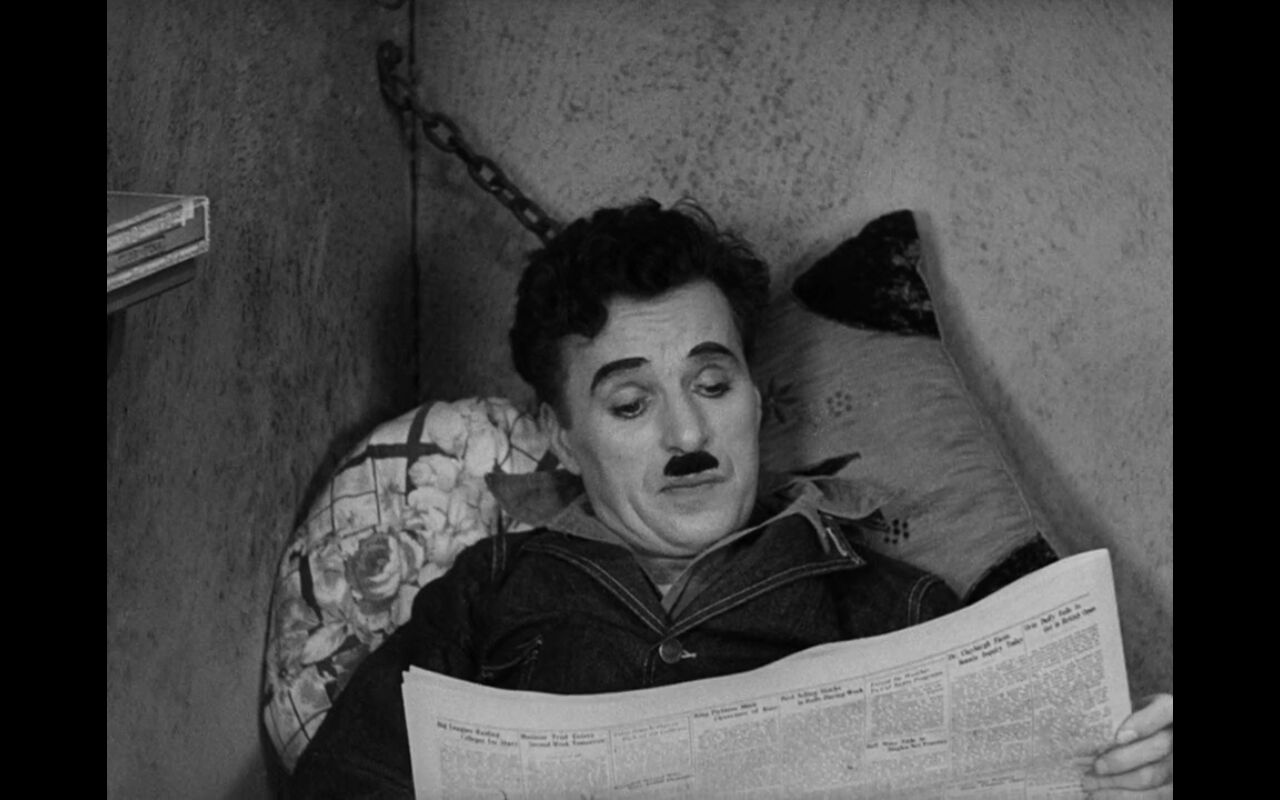

Charlie Chaplin, film stills from Modern Times, 1936.

The Reverse Image

Lefebvre most importantly applied his notion of the reverse image to culture that generates reverse images of everyday life. He claimed that reverse images posed ‘a complex problem, both aesthetic and ethical... [and that they were images] of everyday reality, taken in its totality or as a fragment, reflecting that reality in all its depth through people, ideas and things which are apparently quite different from everyday experience, and therefore exceptional, deviant, abnormal.’Lefebvre, Critique, 12. New color photography was a new form for this kind of reverse image of everyday life in the sense that it utilised the mundane and commercial nature of the everyday life of the late capitalist sprawl to create an entrancing reverse image. Photographs became illuminating backdrops that everyday life lacked – they were the settings missing from everyday life. Lefebvre used Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea and Virginia Wolfe’s A Room of One’s Own to illuminate this point: ‘But a book like Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea also contains a reverse image – that of the toil, the illusions and the failures of individual and “private” everyday life. He presents these in all their profound drama, while placing them in the very setting that they lack: the luminosity of the sea, the immensity of the horizon.’Lefebvre, Critique, 259.

For Lefebvre, cultural presentations of everyday life that utilised a reverse image (the inversion of the mundane or tumultuous into something sublime) were ultimately critiques of everyday life. Lefebvre observed that ‘in the contemporary period, art and philosophy have drawn closer to everyday life, but only to discredit it, under the pretext of giving it a new resonance.’Lefebvre, Critique, 130. Here, Lefebvre was drilling home a dialectic of everyday life in culture, a process that is still constantly evolving. On the one hand, art and philosophy uses everyday life as a subject. On the other, culture then critiques everyday life and the social context that creates it and is created by it. In this critique, there’s the potential to resonate anew with everyday life and its importance in imagining and planning new political and economic systems.

Lefebvre expanded on this critique of the politico-economic system in referencing Charlie Chaplin to compellingly describe the reverse images of the artist and the art:

[Chaplin] comes as a stranger into the familiar world, he wends his way through it, not without wreaking joyful damage. Suddenly he disorientates us, but only to show us what we are when faced with objects; and these objects become suddenly alien, the familiar is no longer familiar… But via this deviation through disorientation and strangeness, Chaplin reconciles us on a higher level, with ourselves, with things and with the humanized world of things.Lefebvre, Critique, 11.

In the movie Modern Times, Chaplin’s character moves through a heavily industrialised world, working in a factory while he’s driven comedically insane by the repletion of the assembly line. The everyday action of work morphs into something that can be comfortably appreciated by the audience through comedy. Chaplin’s insanity lands him in jail, and he finds his life in jail is much more fulfilling than working in a factory. This point was echoed by Fisher in the twenty-first century, when he claimed that ‘[o]nly prisoners have time to read, and if you want to engage in a twenty-year long research project funded by the state, you will have to kill someone.’Fisher, K-Punk, 518. For instance, many of the radical leaders of the 1960s in the United States, such as Malcolm X and Eldridge Cleaver, read and learned revolutionary history and theory while in prison, although it was anything but a luxurious experience.Modern Times shows a reverse image of everyday life in which factory work is a comedic activity, but it’s also a very clear critique of industrialisation, which created unbearable everyday lives.

This was echoed in Chaplin’s own experience when he was the target of a smear campaign by the FBI for being suspected of communist sympathies. He was denied entry into the United States (his character in Modern Times was arrested for a similar reason), and he ended up saying, ‘I would like to have told [the U.S. government] that the sooner I was rid of that hate-beleaguered atmosphere the better, that I was fed up of America's insults and moral pomposity.’Charles Chaplin, My Autobiography (London, United Kingdom: Penguin Books, 2003), 455. One can walk away from Chaplin’s films critical of capitalism and the United States, but at the same time and not unlike the aesthetic permeating Eggleston’s and Shore’s works, there’s a liberating optimism in walking out of the theatre or putting down the photobook and feeling inspired – a feeling of being at sea.

The sublime characteristic of new color photography, then, worked on two levels; it obscured the social nature of what was photographed and the political and economic worlds that existed behind it, like the fetishism of commodities, while at the same time acting as a vessel for imagining better futures in which everyday life could be revolutionised to evolve past the toil and mundanity of the everyday, which would involve changing the political and economic context that created, and was created by, everyday life. The relationship between aesthetics, politics and everyday life in new color photography was a dialectical process that was constantly intermingling and shifting; each was essential to understanding new color photography.

New Futures

Though the new color photography movement that started in the United States with Eggleston and Shore was relatively apolitical throughout the 1970s, it was nonetheless a critique, although the enemy might have appeared unseen from a simple aesthetic standpoint. Lefebvre observed that early mankind ‘knew full well how to distinguish between the sacred and the secular, the everyday and the sublime, while for us these two elements of their lives seem inextricably merged.’Lefebvre Critique [Volume 2 in the one-volume edition] (New York: Verso, 2014), 615. This merging of the everyday and the sublime is what stunts the political potentials of new color photography.

The new color photography movement grew, culminating in Britain in the 1980s with photographers like Paul Graham, Anna Fox, Martin Parr and Paul Reas, who were more direct in their politics of everyday life, not shying away from the enemy. Graham photographed the waiting rooms of social security and unemployment offices as Thatcher was undermining the programs they ran. Fox and Reas were blunt in their photographing of retail and commercial spaces, and Parr’s images of commodities and other oddities exposed the hollowed fetishisation of them. Thatcher’s neoliberal austerity attacks on the welfare system were much more apparent than the struggles captured by the new color photography of the 1970s, but both show everyday life in order to critique it and the systems that generate it. In this critique, we see a recognition that new kinds of everyday life are possible.

The new color photography movement must be looked at through Marx’s and Lefebvre’s analyses to expose it’s utopian potential and liberate the movement from the chains of aestheticization and nostalgia. As Fisher said of punk and surrealism, new color is ‘dead as soon as it is reduced to an aesthetic style.’Fisher, K-Punk, 120. Although analysis is a very contemplative and seemingly subjective act, it’s the first step towards a formulated proactive praxis. Marx famously claimed that ‘philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways. The point, however, is to change it.’Karl Marx, Theses on Feuerbach from Engels Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy (Foreign Languages Press, 1976), 65.

The same could be said of photographers who have only collected the world in various ways. The point is to use the medium to change it.