You’ll encounter three photographs in this article. Two of them can be consulted in the bright reading room of the Belgian State Archives, and the other is available at the Royal Museum for Central Africa. The images share certain qualities. Each one depicts a river embedded in Central African scenery. Otherwise cascading water has been brought to a standstill by the wink of the camera’s shutter. The colourful landscapes have turned monochrome. The three photographs were shipped to Belgium, along with the imperial enterprise. They refer to the past. They were captured by a subject, showing an object. A camera was used.

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay argues that when a photograph is taken, three dividing lines are drawn. She refers to these dividing lines as the operation of ‘the imperial shutter’. The first line is drawn in time. A division is made between before and after. The scene becomes relegated to history and separated from the present and future. The second line is drawn in space, making a division between who or what is in front of the camera and who or what is behind it. This line sharply distinguishes object and subject, granting adjacent rights and privileges exclusively to the latter. The third line is drawn in the body politic. Those who possess and operate the camera and thus appropriate and accumulate its products are divided from those whose countenance, resources, or labour are extracted. Who can govern is demarcated from who’s governed.Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (London: Verso, 2019), 5. These divisions are instrumental; they function to neutralise imperial rule and its dualisms.Azoulay, Potential History, 25.

The three photos invite us to look across those dividing lines. They question and undermine the imperial shutter’s operation, revealing the unstable character of the divisions. We’ll hear the photographs scream in present tense and argue from the point of view of the object, questioning our ideas about who’s governing and who’s to be heard and seen. In doing so, the encounters in time, space, and the body politic become available in the archives.

Time: before encounters after

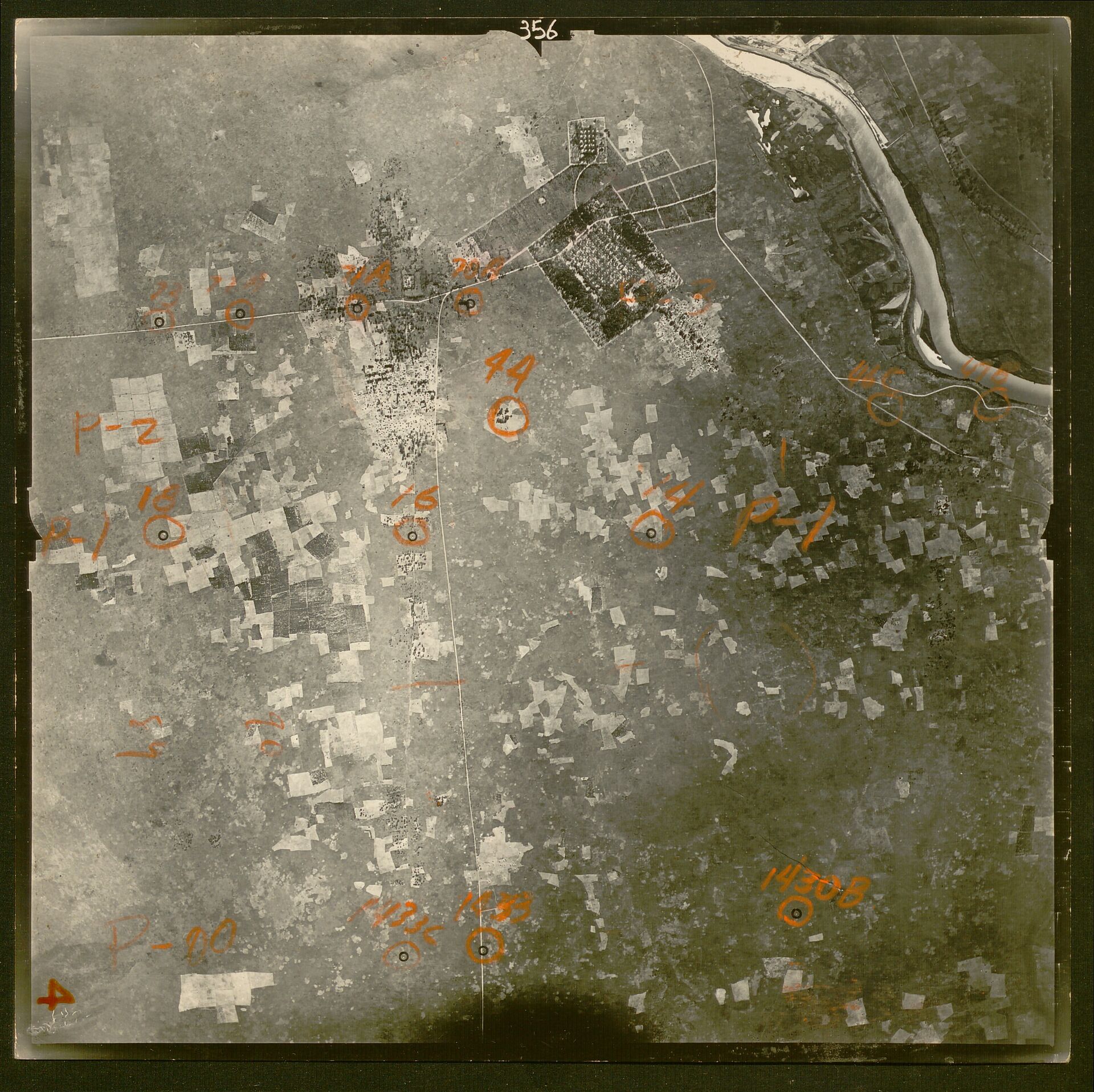

The first photograph shows the Kanshi Valley, located in the Haut-Katanga province of Congo. From an aerial perspective, the black-and-white patchwork of fields blends with the miniature buildings and streets. A wide river meanders in the upper right corner. On the print of the photo itself, someone has drawn various orange numbers and circles on the landscape. The photograph refers to the past.

Mission Fairchild, 1955, photograph, Folder 1736, Sibeka, Belgian National Archives 2 – Joseph Cuvelier Repository, Brussels.

The Kanshi Valley was captured in 1955 by an employee of Fairchild Aerial Surveys. His job was to map the valley and pinpoint possible sites for diamond mining. The orange marks indicate those areas.Correspondence with Fairchild Aerial Surveys, Inc., 1955–1958, Folders 1729–1731, Sibeka, Belgian National Archives 2 – Joseph Cuvelier Repository, Brussels. This was crucial information for the various exploitative mining companies active in the region at that time, the Belgian company Sibeka being among them. During and after colonisation, Sibeka expropriated diamonds from the valleys of Congo. The imperial enterprise then shipped this photograph to Belgium. There, it became classified, time-stamped, and integrated into the Sibeka records, guarded by the Belgian State Archives. Today, we can consult the image in one of its depots in Brussels.

When the photograph was taken, a dividing line in time was drawn. Before was separated from after. The circumstances in which the valley was registered are divided from our physical presence in the archive today. Various archival procedures of meticulous classification enforce this distinction. The photo is guarded in a filing cabinet, stored between dated letters and correspondence, wrapped in dusky pink paper. By treating it this way, the archive attempts to take control of the statement that can be made about our colonial legacy.Azoulay, Potential History, 173–175. We’re invited to study the image as if it’s a speechless record of the past. The Kanshi Valley has been stripped of its contemporary relevance. In the reading room, it’s safely removed from public opinion and reparation claims. By storing the photo away in filing cabinets, in the basement, out of view, the archives suggest that what can be consulted in it has already been processed.

Categorizing what’s guarded in the Sibeka archive as ‘past’ lays claim to present readings. When we relate to the photograph as a carrier of history, as the archive wants us to perceive it, we suggest that its implications also lie in the past. At that point, the Kanshi Valley must disagree. The photograph screams in the present tense, manifestly raising questions: How did these records come into existence? What is the relevance of the photo today? What can we see in the encounter between before and after?

Tracing the photo back to its origins would first lead us to the expropriation of diamonds by Sibeka. Under their direction, communally owned lands were converted into mining sites.Richard Derksen, ‘Forminière in the Kasai, 1906-1939.’ African Economic History 12 (1983): 49-65, 50-52. The whole Kanshi Valley became a potential extraction zone. Simultaneously with the extraction of those raw materials, other forms of expropriation took place. The land and the people who inhabited it supplied data for geographical research and the development of mining techniques. Congolese contacts provided social connections and indispensable expertise. As guides and translators, they were crucial bridges and building blocks for the imperial company. Yet little is known about their exact roles and contributions.Ethical Principles for the Management and Restitution of Colonial Collections in Belgium, Restitution Belgium, June 2021, accessed June 2022, https://restitutionbelgium.be/en/report. Nor are they credited for their work. Finally, with the abundance of material available in the archive, another form of expropriation is made possible. Today, the looted records supply material to construct meaning. In the archive, researchers gather to write, analyse, and produce knowledge with data that was taken with violence, without permission.Azoulay, Potential History, 165. On the wooden desk, in a quiet atmosphere, the cabinet’s contents can be laid out to dissect the atrocities harboured there from the objective viewpoint of the researcher. The visit becomes an act of data extraction.

We speak of extraction because the excess of access by some implies that others are denied these resources.Azoulay, Potential History, 185. Although the photograph constitutes a shared colonial heritage, only people who can physically access the reading room can consult it. Most people in Congo or the Congolese diaspora elsewhere cannot conduct the research I’m carrying out here and now. The archive enables the researcher, who inherited the wealth of data, to ask for documents about those who are deprived of this right – as if the archive, which is invested in stripping the files of their present tense, could produce anything other than propaganda files to sustain itself. Further building upon this knowledge, the researcher continues to employ these privileges to occupy the position of an expert.Azoulay, Potential History, 165. The expropriated data provides the material that white academia converts into theory.Sara Ahmed, What’s the Use? On the Uses of Use (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019), 189. Our access to the archive is not determined by our shared past, present, and future. It's determined by the operation of the imperial shutter. The dividing line in time extends to today – to who can access the records – and it continues historical and colonial inequality by doing so.

The State Archives are well aware of the restrictions in access. At present, no plans have been made to share the records with Congo.Joachim Derwael, email message to Monica Fierlafijn, May 27, 2021. However, as part of their ‘actions for decolonisation’, the archives have set up the FormArch and the ImmArch programs.‘Koloniaal Archief’, Belgian National Archives 2 – Joseph Cuvelier Repository, Brussels. These programs are framed as professional development training opportunities in archival science. Candidates from Burundi, Congo, and Rwanda can apply.‘Internships and Scientific Visits’, Royal Museum for Central Africa, accessed June 20, 2021, https://www. africamuseum.be/en/ research/training. After a far-reaching and highly competitive selection process, a group of fourteen students are selected to participate. Following a three-month training program, another selection process is carried out.‘ImmARCH – Appel à Candidatures’, ImmARCH – Appel à Candidatures (Brussels: Royal Museum for Central Africa, 2021). Two to three trainees 'who have followed the entire program with seriousness and diligence and who have passed the tests for each stage’ are then chosen to conduct their research in the ‘breast’ of the archives in Belgium – meaning the bright reading rooms that I can enter whenever it suits me. The FormArch and ImmArch programs run in the context of Belgian development cooperation, which is motivated by the need to ‘share its standards and participate in the training of future young colleagues’.‘ImmARCH – Appel à Candidatures’ I wonder what these standards include – the métier of turning acts of violence into historical data?

In the tracks of the photograph of the Kanshi Valley, certain researchers are now ‘elected’ to cross the same distance. Via the two programs, the Belgian government pays lip service to the urgent need to consider the archives in the present tense. The expropriated resources are partially restituted in the guise of access to expertise. This is not only extremely limited restitution but the government also praises itself for this so-called ‘development cooperation’ to boot. We cannot let the narrative slip into an upward arc of aid and benevolence. The (visual) material guarded in the Sibeka archive was, quite frankly, never ‘ours’ to begin with, and neither can the State Archives choose the conditions under which people can access the data. The fact that an institution in Belgium gets to choose who writes history with the archival records only reinforces the imperial shutter’s bias. In doing so, it lays claim to future possible readings and interpretations. An elementary requirement to engaging with our history is unrestricted access to the records.Azoulay, Potential History, 165. Rather than relegating the photograph to the past, we must allow the different tenses to encounter one another. When looking across the diving line in time, we can see how the archive has invited us to forget that our access is entangled with the access of others.

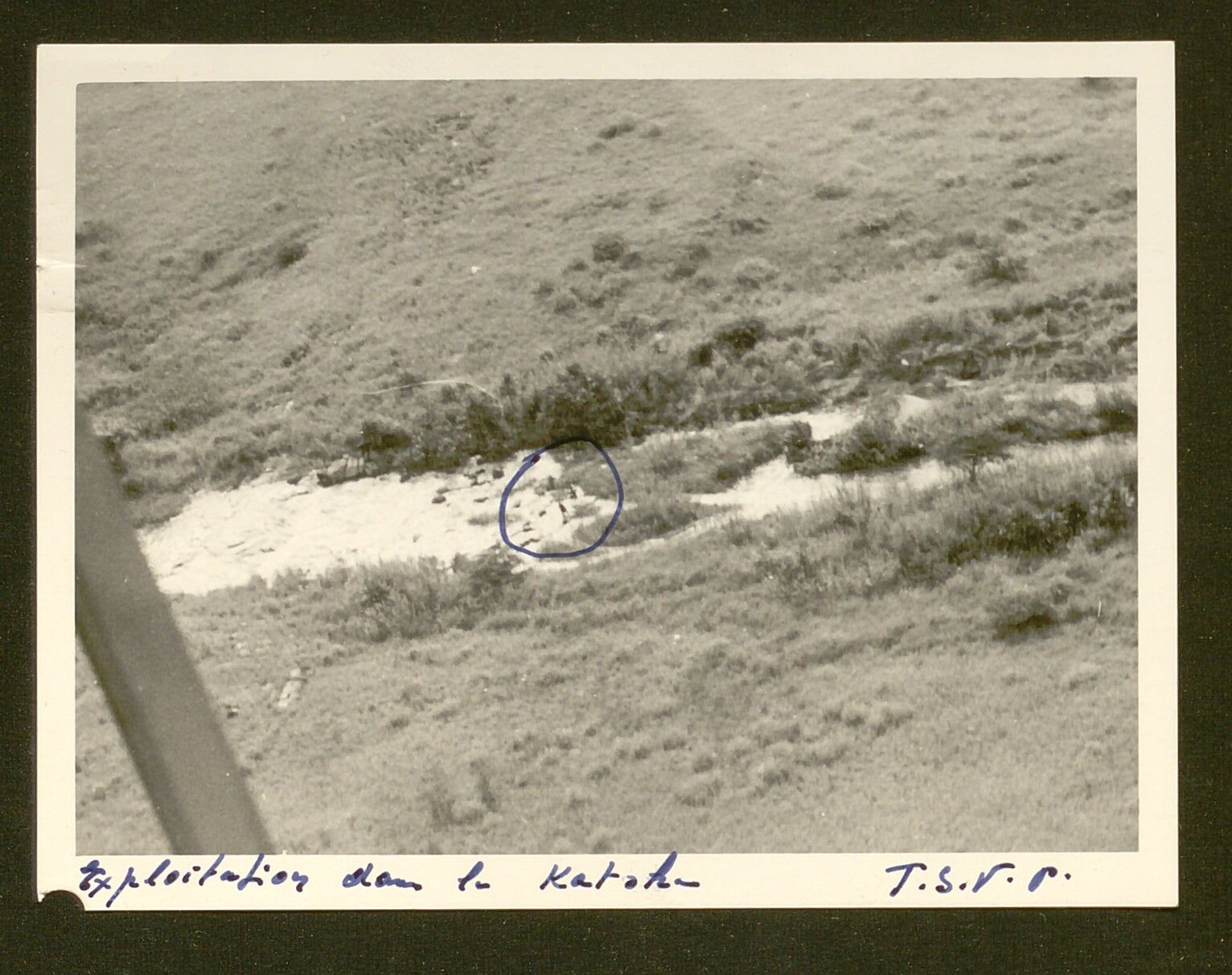

Mission Louis Piron, 1958–1960, Folder 1423, Sibeka, Belgian National Archives 2 – Joseph Cuvelier Repository, Brussels.

Space: subject encounters object

The second photograph depicts the Katoka Stream in north-western Zambia. It’s a straightforward black-and-white registration. The river is surrounded by pasture, and its central part is circled in blue. The rectangular format is enclosed by a white frame. Though the handwriting is a bit messy, the words on the frame appear to say ‘Exploitation dans la Katoka, T.S.V.P.’ The photograph was captured by a subject, showing an object.

This record of the Katoka Stream belongs to the same archives as the Kanshi Valley photograph. Both attest to the expropriation carried out by Sibeka. They are part of an extensive collection of photo albums, negatives on glass plates, and large prints carefully documenting years of colonial atrocities. At first glance, one might presume that the blue circle carries similar information to the orange marks on the photograph of the Kanshi Valley, indicating a possible mining site. However, the photo of the stream invites us to take up the object’s perspective. At that point, the inscription’s connotation changes entirely.

When the photo was taken, a dividing line in space was drawn. Who or what was in front of the camera was separated from who or what was behind it. When we consult the Sibeka records today, the subject’s perspective is widely available. Our eyes are tricked into seeing only what the person behind the camera wanted to show. The rivers are portrayed from the perspective of the colonial employees. Through their eyes, the land is transformed into potential mining sites. From their perspective, the ruthless expropriation is justified. Due to the nature of the records, which were mainly written and captured from the positionality of the coloniser, the archives could not possibly attest to the lives and livelihoods of the people stored within them. Records made by the people who inhabited the registered landscapes are missing. The object’s perspective is absent. Nevertheless, this archival absence must not lead us to deny their active presence.Azoulay, Potential History, 371.

Suppose the available filing cabinets in the reading room don’t contain records of their presence, agency, or resistance. In that case, every photograph taken in the same unit of time and space can function as a substitute.Azoulay, Potential History, 238–240. Azoulay proposes using the existing photos as placeholders in a photographic archive in formation.Azoulay, Potential History, 239. Other narratives and gazes can be situated among those already available.Azoulay, Potential History, 238–240. The archive attempts to hold on to the imperial shutter’s dividing lines through its hosting of still scenes shown from the object’s point of view. When the photo of the Katoka Stream becomes a placeholder, it can function as an amplifier for telegraphed statements of the object portrayed, antagonising its archival genre.Brian Wallis and Tina M. Campt, ‘The Sound of Defiance’, Aperture, 25 October 2017, https://aperture.org/editorial.... In the encounter with the camera, what did the object reveal to the state, to themselves, and to us? What if the subject’s perspective is rephrased? What do we see in the encounter between subject and object?

The photo of the Katoka Stream is incorporated into a pile of correspondence, notes, and reports. These are hand-written or typed on a typewriter, alternately in Dutch and French. After browsing through some, unravelling the bureaucratic grammar, I came to understand that the filing cabinet contains the records of mining security and the repression of illegal diamond trafficking. The blue circle on the photo indicates one of those unauthorized mining sites. The sheer quantity of letters and comprehensive charts is evidence that illegal mining and dealing of diamonds by the Congolese was extensive in the Sibeka company’s areas. As part of the Mission Louis Piron, several people were sued for stealing diamonds. On a daily basis, people were arrested for digging in the rivers and mines.Judicial Reports and Correspondence, 1958–1960, Folder 1423, Sibeka, Belgian National Archives 2 – Joseph CuvelierRepository, Brussels. The judicial reports specify and attest to their heavy punishments and fines. In one of the reports on the surveillance missions, there is mention of certain groups who stole documents from the colonial administrative buildings.

Perhaps people took these documents because they included valuable information on which areas qualified for diamond mining, or perhaps the files attested to the illegal trafficking of diamonds, which could be damaging for certain Congolese and other labourers. Either way, when the photograph is comprehended from the object’s point of view, ‘stealing’ can be rephrased as ‘using what’s yours’. The expropriation of resources was carried out by colonial means in the first place. Therefore, independent mining was only illegal from the imperial enterprise’s perspective. When we shift to the object’s perspective, ‘illegal exploitation’ becomes a euphemism for ‘expropriating the expropriator’.Quote of Karl Marx revisited in Étienne Balibar, ‘Revisiting the “Expropriation of Expropriators” in Marx’s Capital’, in Marx’s Capital After 150 Years (Routledge: 2019), 39–53. What was taken away with violence, without permission, is reclaimed. Through mining and taking documents, the people showed that the land belonged to them and that they could decide on its use.

Day by day, people who lived under Belgian colonial rule defended their right to their land. The everyday practice of independent mining attests to their resistance to Sibeka’s division of roles. The agency of the colonised people necessarily occurs outside of the archival grammar. Relating to these acts available in the archive as forms of resistance rather than crimes, centres and affirms the voices of the people portrayed. At this moment, the fixed role of object, relegating who is in front of the camera to a passive role, becomes ambiguous again. When we look across the dividing line in space, we can see the people who were mining independently reclaim their subject role. Connecting their agency to these photos ensures that its records are less likely to disappear.Wallis and Campt, ‘The Sound of Defiance’. In the circled part of the stream, the agency of those who had been turned into objects of data is made material.

Body politic: governed encounters governing

The third photograph depicts the Bembezi Stream, located in Bas-Congo. This sepia-tone registration of the landscape is taken from a distance yet feels affectionate. The stream runs from the lower-left corner to the upper-right. In the middle, we can discern a hill, and trees are spilt over the panorama. A camera was used.

Soon after its invention in 1839, photography became entangled with European colonialism.Teju Cole, ‘When the Camera Was a Weapon of Imperialism (And When It Still Is)’, The New York Times, 6 February 2019, https:// www.nytimes. com/2019/02/06/magazine/ when-the-camera-was-a- weapon-of-imperialism-and- when-it-still-is.html. The camera was almost immediately turned on the ‘new worlds’ to register the people and lands the European states were conquering.Alison Devine Nordstrom, ‘Persistent Images: Photographic Archives in Ethnographic Collections’. Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies 6, no. 2 (1993): 207–219. In recent work on the imperial othering of subjected people, the camera is often referred to as the most appropriate metaphor for the intrusive colonial gaze in Africa.Terence Ranger, ‘Colonialism, Consciousness and the Camera’, Past & Present 171 (2001): 203–215. Via the imperial shutter’s dividing lines in the body politic, roles were assigned in the imperial enterprise. As noted above, those who operated the camera and accumulated its revenues were divided from those whose resources were extracted.Azoulay, Potential History, 5 Relations between the imperial employees and the colonised people were structured, often forcibly, along these dividing lines. However, many other role patterns also occurred. In the same space and time unit, ample stories attest to the photographic object’s subverting of the photographer’s intent, as they came to operate the camera and adopt the medium on their own terms.

Shanu Herzekiah-Andrew, Vue De La Bembezi, 1898, photograph (Tervuren, n.d.), Royal Museum for Central Africa.

Since well before the end of the nineteenth century, in different parts of Congo as well as in other parts of Africa, colonised people turned photography to their own use. This included both elite appropriations and democratic seizures of the medium. When photography was still complicated and expensive, people did not have the resources to employ the medium themselves. Instead, they adapted the white framing to their own needs, taking up the poses they wished.Ranger, 'Colonialism, Consciousness and the Camera’, 206–209. By both playing along with the Western photographers and simultaneously directing relations with them, they used the photographs to project their identity and articulate their political aspirations to the spectators.Ranger, 'Colonialism, Consciousness and the Camera’, 206–209.

Later still, as cameras became cheaper, people acquired equipment and established studios, first in the coastal regions and then in inland towns.‘In and Out of Focus: Images from Central Africa 1885–1960’, The National Museum of African Art – Smithsonian Institution, accessed 14 June 2021, https://africa.si.edu/exhibits... focus/encounters.html. Lower Congo was a melting pot of different populations; aside from the colonial administrators, West Africans from the coastal regions, Angolan refugees, and sailors of all nationalities encountered each other at the maritime gateways of the Congo River. The first African photographs in the Belgian colony were often taken by travellers, Antoine Freitas, Lema, and Herzekiah Andrew Shanu being among them. At that time, street photographers were also becoming active, and itinerant photographers went from village to village with their box cameras and detachable settings.N’Goné Fall, ‘Les Mondes Parallèles’, in Kinshasa Photographers, ed. N’Goné Fall (Paris: Revue Noire, 2001), 10. Although photographers were in the beginning often met with hostility for various reasons, the medium was later adopted in rituals.Fall, Kinshasa Photographers, 10. People were formulating their own uses and expectations of photography, deciding which moments justified being fixed in time.

In 1898, Nigerian-born Shanu fixed the photograph of the Bembezi Stream.Shanu, Vue De La Bembezi. This photograph is part of a more extensive collection guarded in the Royal Museum for Central Africa. Around sixty photographs presumably taken by Shanu can be consulted in the form of glass plates and clichés.'The Photos of Herzekiah- Andrew Shanu,’ Royal Museum for Central Africa, accessed 2 June 2021, https://www.africamuseum. be/de/discover/focus_collection/ display_group?groupid=358. His photos are guarded in Belgium because Shanu worked for the Belgian colonial government of the Congo Free State. Likely attracted by the professional opportunities the International Association of the Congo offered, he moved from Lagos to the Belgian colony. There, he first worked as a clerk and translator and later as assistant commissioner of the district. After nine years of service, Shanu decided to leave and build his own prosperous business in Boma.Fall, Kinshasa Photographers, 16. He combined various activities in the hotel industry with the sale of food products and ready-to-wear clothing. He also took an interest in photography, and some of his photos were published in the Brussels magazine Le Congo Illustré.Adam Hochschild, King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: 1999), 530. During the 1894 World Fair in Antwerp, Shanu travelled to Europe and was invited to give several lectures, particularly at the Association for Colonial Studies. Appreciated by his former employers and much welcomed to praise Leopold II’s rule in Congo, Shanu had aligned himself with the colonial oppressor.

In 1903, however, something caused a change of heart, and Shanu completely turned this back on the imperial administration. For a Black man residing in the capital of the Belgian Congo, this was extremely courageous.Hochschild, King Leopold’s Ghost, 530. Shanu began supplying Roger Casement, a British consular officer in Boma, with information about the mistreatment of West African workers in Congo. Via Casement, Shanu got to know the Congo Reform Association. At that time, Edmund D. Morel was mounting an anti-Leopoldian campaign in Europe. Shanu asked Morel to send him some of his writings, and the latter was very pleased to find a potential ally in the heart of the capital. For several years, Morel and Shanu corresponded as they worked to end slavery and other humanitarian abuses in the Congo Free State.Fall, Kinshasa Photographers, 14. The information Shanu sent included, notably, transcripts of trials against low-ranking Congo Free State officials.Hochschild, King Leopold’s Ghost, 531–533. Prompted by protests in Europe against Leopold II’s rule, the colonial authorities in Congo had made a big show of prosecuting these officials for atrocities against the Congolese people. However, these trials proved to be damaging for the colonial government, since the defendants accused of horrific murders usually said they were only following orders. Therefore, the transcripts were kept secret until Shanu acquired access and Morel published them.Hochschild, King Leopold’s Ghost, 530.

Unfortunately, in addition to being indispensable, the work Shanu carried out was also immensely dangerous. During his further involvement in the Congo Reform Association, he was betrayed by a state official who disclosed his work as an informant. The colonial authorities harassed him unremittingly and ordered all state employees to boycott his businesses, which caused him to go bankrupt. In July 1905, Shanu committed suicide.Hochschild, King Leopold’s Ghost, 535.

With his activist work and immense courage, Shanu forces us to revise the shutter’s dividing lines. His photography highlights the instability of the divisions. More than a century ago, Shanu operated the camera and, in doing so, resisted the role patterns fixed by the imperial enterprise. He governed the governing. Through his records, we can envision where the encounters across the body politic might take us. If we look attentively at the image of the Bembezi Stream, we can discern, in the middle right, a wooden bridge built over the river. It connects the uphill part of the scene with what takes place outside of the frame. Through the photo, we’re offered a lens through which the oppressor can position themselves with the oppressed, on the latter’s conditions.

Encounters across

When before encounters after, the existence of the Sibeka archive becomes entangled with our access to the records today. Our presence in the archive’s reading room runs parallel to the reality of the ImmArch and FormArch programs, which offer extremely limited restitution and biased history writing. When subject encounters object, we can become attuned to the active presence of the people portrayed. Materialised in the circled part of the stream, the practices of independent mining attest to the resistance to the shutter’s operation. When governing encounters governed, the dividing lines reveal their unstable character. People’s roles in operating the camera were constantly transformed and traded; power and the ability to act shifted regularly. These narratives highlight the resistance to the imperial shutter.

The photographs of the Kanshi Valley, Katoka Stream, and Bembezi Stream share one critical aspect: they offer lenses through which we can look across these dividing lines. The moment we accept their invitation, we challenge the imperial shutter’s order of time, space, and the body politic. In this refusal to settle with the easily available readings in the records lies the practice of encountering. When we take a last glance, we notice that the streams are no longer halted by the archive.

This article is a reworked and shorted version of my master's dissertation ‘How to see these photographs? Encounters in time, space, and the body politic through an uneasy reading’. If you would like to read the full dissertation, provide additional readings, or offer critique, don’t hesitate to get in touch. You can reach me at monica.fierlafijn@protonmail.com.